Assignment Afghanistan

From keeping tabs on the Taliban to saving puppies, a reporter looks back on her three years covering a nation’s struggle to be reborn

As my eyes adjusted to the dark and gloomy schoolroom, I could see the men more clearly, their woolen shawls drawn up against their tough and leathery faces. They were farmers and herders who lived hard lives on meager land, survivors of foreign occupation and civil war, products of a traditional society governed by unwritten rules of religion and culture and tribe where Western concepts like freedom and happiness were seldom invoked.

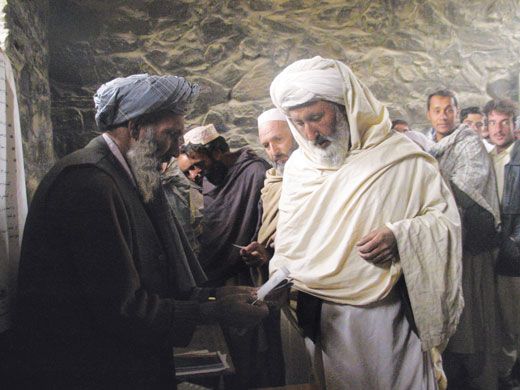

But there was something I had not seen before in the faces of these turbaned villagers; an almost childish excitement, a look both nervous and dignified: a feeling of hope. It was October 9, 2004, and they were among 10.5 million voters who had registered to elect the first president in their country’s history. No one shoved or jostled as the line inched toward a pair of scarred school benches, where two elderly officials were checking off ledgers, marking thumbs with purple ink, murmuring instructions: “There are 18 candidates for president, here are their names and pictures, mark the one you want, but only one.” Then they handed each man a folded paper and motioned him politely toward a flimsy metal stand curtained with a red gingham cloth.

I positioned myself behind one of the benches. I wanted to remember this day, this hushed and universal ritual of a fledgling democracy that once had seemed impossible to imagine. In another week, I would be leaving the country after nearly three years that had been among the most exhilarating, as well as the most grueling, of my career as a foreign correspondent.

During that time I had covered the assassinations of two cabinet ministers, tiptoed through the human wreckage of car bombings, chronicled the rapid spread of opium poppy cultivation, witnessed the release of haggard war prisoners and the disarming of ragged militiamen. But I had also traveled with eager refugees returning home from years in exile, visited tent schools in remote villages and computer classes in makeshift storefronts, helped vaccinate flocks of sheep and goats, watched parched and abandoned fields come alive again, and reveled in the glorious cacophony of a capital city plugging into the modern world after a quarter-century of isolation and conflict.

Even on days when I awoke feeling as if there were little hope for the country and less I could do to help, invariably something occurred that restored my faith. Someone made a kind gesture that dissipated the poison around me, told me a tale of past suffering that put the day’s petty grievances in new perspective, or expressed such simple longing for a decent, peaceful life that it renewed my determination to make such voices heard above the sniping and scheming of the post-Taliban era.

On this particular day, it was the look on a young farmer’s face as he waited to vote in a chilly village schoolroom. He was a sunburned man of perhaps 25. (Once I would have said 40, but I had learned long ago that wind and sand and hardship made most Afghans look far more wizened than their years.) He was not old enough to remember a time when his country was at peace, not worldly enough to know what an election was, not literate enough to read the names on the ballot. But like everyone else in the room, he knew this was an important moment for his country and that he, a man without education or power or wealth, had the right to participate in it.

The farmer took the ballot gingerly in his hands, gazing down on the document as if it were a precious flower, or perhaps a mysterious amulet. I raised my camera and clicked a picture I knew I would cherish for years to come. The young man glanced up at me, smiling shyly, and stepped behind the gingham curtain to cast the first vote of his life.

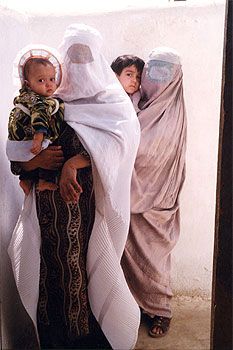

I first visited Afghanistan in 1998, a dark and frightened time in a country that was exhausted by war, ruled by religious zealots and shut off from the world. Kabul was empty and silent, except for the squeak of carts and bicycles. Entire districts lay in ruins. Music and television had been banned, and there were no women on the streets except beggars hidden beneath patched veils.

For a Western journalist, the conditions were hostile and forbidding. I was not allowed to enter private homes, speak to women, travel without a government guide or sleep anywhere except the official hotel—a threadbare castle where hot water was delivered to my room in buckets and an armed guard dozed all night outside my door. Even carefully swathed in baggy shirts and scarves, I drew disapproving stares from turbaned gunmen.

Interviews with Taliban officials were awkward ordeals; most recoiled from shaking my hand and answered questions with lectures on Western moral decadence. I had few chances to meet ordinary Afghans, though I made the most of brief comments or gestures from those I encountered: the taxi driver showing me his illegal cassettes of Indian pop tunes; the clinic patient pointing angrily at her stifling burqa as she swept it off her sweat-soaked hair.

I visited Afghanistan that first time for three weeks and then nine more times during Taliban rule. Each time the populace seemed more desperate and the regime more entrenched. On my last trip, in the spring of 2001, I reported on the destruction of two world-renowned Buddha statues carved in the cliffs of Bamiyan, and I watched in horror while police beat back mobs of women and children in chaotic bread lines. Exhausted from the stress, I was relieved when my visa expired and headed straight for the Pakistan border. When I reached my hotel in Islamabad, I stripped off my dusty garments, stood in a steaming shower, gulped down a bottle of wine and fell soundly asleep.

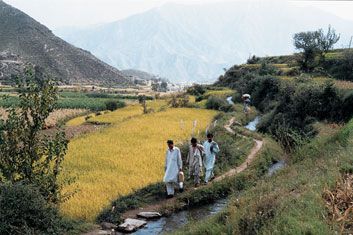

The first sprigs of green were poking up from the parched winter fields of the Shomali Plain stretching north from Kabul. Here and there, men were digging at dried grapevine stumps or pulling up buckets of mud from longclogged irrigation canals. Bright blue tents peeked out from behind ruined mud walls. New white marking stones had been neatly placed on long-abandoned graves. Along the highway heading south to Kabul, masked workers knelt on the ground and inched forward with trowels and metal detectors, clearing fields and vineyards of land mines.

It had been a year since my last visit. From the terrible ashes of the World Trade Center had risen Afghanistan’s deliverance. The Taliban had been forced into flight by American bombers and Afghan opposition troops, and the country had been reinvented as an international experiment in postwar modernization. Within a month of the Taliban’s defeat, Afghanistan had acquired a dapper interim leader named Hamid Karzai, a tenuous coalition government, pledges of $450 million from foreign donors, a force of international peacekeepers in Kabul, and a blueprint for gradual democratic rule that was to be guided and financed by the United Nations and the Western powers.

For 35 months—from November 2001 to October 2004—I would now have the extraordinary privilege of witnessing Afghanistan’s rebirth. This was a journalist’s dream: to record a period of liberation and upheaval in an exotic corner of the world, but without having to be afraid anymore. As on my trips during the Taliban era, I still wore modest garments (usually a long-sleeved tunic over baggy trousers) in deference to Afghan culture, but I was free to stroll along the street without worrying I would be arrested if my head scarf slipped, and I could photograph markets and mosques without hastily hiding my camera under my jacket. Best of all, I could chat with women I encountered and accept invitations to tea in families’ homes, where people poured out astonishing tales of hardship and flight, abuse and destruction—none of which they had ever shared with a stranger, let alone imagined seeing in print.

Just as dramatic were the stories of returning refugees, who poured back into the country from Pakistan and Iran. Day after day, dozens of cargo trucks rumbled into the capital with extended families perched atop loads of mattresses, kettles, carpets and birdcages. Many people had neither jobs nor homes awaiting them after years abroad, but they were full of energy and hope. By late 2003, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees had registered more than three million returning Afghans at its highway welcome centers.

I followed one family back to their village in the Shomali Plain, passing rusted carcasses of Soviet tanks, charred fields torched by Taliban troops, and clusters of collapsed mud walls with a new plastic window here or a string of laundry there. At the end of a sandy lane, we stopped in front of one lifeless ruin. “Here we are!” the father exclaimed excitedly. As the family started unloading their belongings, the long-absent farmer inspected his ruined vineyards—then graciously invited me back to taste his grapes after the next harvest.

Another wintry day I drove up into the Hindu Kush mountains, where the main highway tunnel to the north had been bombed shut years before and then lost beneath a mountain of ice. I will never forget the scene that met my eyes through the swirling snow: a long line of families, carrying children and suitcases and bundles toward the tunnel, edging down narrow steps and vanishing inside the pitchblack passageway cut through the ice.

I tried to follow, but my hands and my camera froze instantly. An arctic wind howled through the darkness. As I emerged from the tunnel, I brushed past a man with a little girl on his back, her naked feet purple with cold. “We have to get home,” he muttered. Ahead of them was a two-hour trek through hell.

The rapidly filling capital also sprang back to life, acquiring new vices and hazards in the process. Bombed buildings sprouted new doors and windows, carpenters hammered and sawed in sidewalk workshops, the air was filled with a clamor of construction and honking horns and radios screeching Hindi film tunes. Traffic clogged the streets, and policemen with whistles and wooden “stop” paddles flailed uselessly at the tide of rusty taxis, overcrowded buses and powerful, dark-windowed Landcruisers—the status symbol of the moment—that hurtled along narrow lanes as children and dogs fled from their path. Every time I sat fuming in traffic jams, I tried to remind myself that this busy anarchy was the price of progress and far preferable to the ghostly silence of Taliban rule.

As commerce and construction boomed, Kabul became a city of scams. Unscrupulous Afghans set up “nonprofit” agencies as a way to siphon aid money and circumvent building fees. Bazaars sold U.N. emergency blankets and plasticpouched U.S. Army rations. Landlords evicted their Afghan tenants, slapped on some paint and re-rented their houses to foreign agencies at ten times the previous rent.

But hard-working survivors also thrived in the competitive new era. During the Taliban years, I used to buy my basic supplies (scratchy Chinese toilet paper, laundry detergent from Pakistan) from a glum man named Asad Chelsi who ran a tiny, dusty grocery store. By the time I left, he had built a gleaming supermarket, filled with foreign aid workers and affluent Afghan customers. The shelves displayed French cheese, German cutlery and American pet food. Aborn entrepreneur, Asad now greeted everyone like an old friend and repeated his cheerful mantra: “If I don’t have what you want now, I can get it for you tomorrow.”

The sound of the bomb was a soft, distant thud, but I knew it was a powerful one and steeled myself for the scene I knew I would find. It was midafternoon on a Thursday, the busiest shopping time of the week, and the sidewalk bazaars were crowded. The terrorists had been clever: first a small package on a bicycle exploded, drawing a curious crowd. Several moments later, a far larger bomb detonated in a parked taxi, shattering shop windows, engulfing cars in flames and hurling bodies in the air. Firemen were hosing blood and bits of glass off the street and sirens wailed. Fruits and cigarettes lay crushed; a boy who sold them on the sidewalk had been taken away, dead.

As my colleagues and I rushed back to our offices to write our reports, news of a second attack reached us: a gunman had approached President Karzai’s car in the southern city of Kandahar and fired through the window, narrowly missing him before being shot dead by American bodyguards. Karzai appeared on TV several hours later, wearing a confident grin and dismissing the attack as an occupational hazard, but he must have been at least as shaken as the rest of us.

The list of those with motive and means to subvert the emerging order was long, but like the taxi bomb that killed 30 people on that September day in 2002, most terrorist crimes were never solved. In many parts of the country, militia commanders commonly known as warlords maintained a tight grip on power, running rackets and imposing their political will with impunity. People feared and loathed the warlords, pleading with the government and its foreign allies to disarm them. But the gunmen, with little respect for central authority and many skeletons left over from the rapacious civil-war era of the early 1990s, openly defied the disarmament program that was a key element of the U.N.-backed plan for transition to civilian rule.

Karzai’s own tenuous coalition government in Kabul was rent by constant disputes among rival factions. The most powerful were a group of former commanders from the northern PanjshirValley, ethnic Tajiks who controlled thousands of armed men and weapons and who viewed themselves as the true liberators of Afghanistan from Soviet occupation and Taliban dictatorship. Although formally part of the government, they distrusted Karzai and used their official fiefdoms in the state security and defense apparatus to wield enormous power over ordinary citizens.

Karzai was an ethnic Pashtun from the south who controlled no army and exercised little real power. His detractors derided him as the “mayor of Kabul” and an American puppet, and after the assassination attempt he became a virtual prisoner in his palace, protected by a squad of American paramilitary commandos sent by the Bush administration.

I observed Karzai closely for three years, and I never saw him crack. In public, he was charming and cheerful under impossible circumstances, striding into press conferences with a casual, self-confident air and making solemn vows for reforms he knew he could not possibly deliver. In interviews, he was effortlessly cordial and relentlessly upbeat, though I always sensed the barely concealed frustration of a leader in a straitjacket. Everyone, perhaps no one more than the president, knew that without American B-52 bombers leaving streaks across the sky at crucial moments, the Afghan democratic experiment could collapse.

Instead the country lurched, more or less according to plan, from one flawed but symbolic political milestone to the next. First came the emergency Loya Jerga of June 2002, an assembly of leaders from across the country that rubberstamped Karzai as president but also opened the doors to serious political debate. Then came the constitutional assembly of December 2003, which almost collapsed over such volatile issues as whether the national anthem should be sung in Pashto or Dari—but which ultimately produced a charter that embraced both modern international norms and conservative Afghan tradition.

The challenge that occupied the full first half of 2004 was how to register some ten million eligible voters in a country with poor roads, few phones, low literacy rates and strong rural taboos against allowing women to participate in public life. After a quarter-century of strife and oppression, Afghans were eager to vote for their leaders, but many feared retaliation from militia commanders and opposed any political procedure that would bring their wives and sisters into contact with strange men.

There was also the problem of the Taliban. By 2003, the fundamentalist Islamic militia had quietly regrouped and rearmed along the Pakistan border. They began sending out messages, warning all foreign infidels to leave. Operating in small, fast motorbike squads, they kidnapped Turkish and Indian workers on the new Kabul to Kandahar highway, ambushed and shot a team of Afghan well-diggers, and then executed Bettina Goislard, a young French woman who worked for the U.N. refugee agency.

Once voter registration began, the Taliban shifted targets, attacking and killing half a dozen Afghan registration workers. But the extremists miscalculated badly. Afghans were determined to vote, and even in the conservative Pashtun belt of the southeast, tribal elders cooperated with U.N. teams to find culturally acceptable ways for women to cast their ballots.

One June day, driving through the hills of KhostProvince in search of registration stories, I came upon a highway gas station with a line of men outside, waiting to have their voter ID photos taken. When I asked politely about the arrangements for women, I was led to a farmhouse filled with giggling women. None could read or write, but a high-school girl filled out each voting card, guessing at their ages, and an elderly man carried them to the gas station. “We want our women to vote, so we have made this special arrangement,” a village leader explained to me proudly. “If they cross the road and some strange driver sees them, people would talk.”

Ballrooms twinkled with fairy lights, amplified music pulsed and pounded, young women in slinky sequined dresses twirled across the floor. Kabul was in a post-Taliban wedding frenzy; a society re-knitting itself and reestablishing its rituals after years of repression and flight. Ornate salons were booked around the clock, and beauty parlors were crammed with brides being made up like geishas.

But despite the go-go glitter, each wedding—like everything related to romance and marriage—was conducted by traditional Afghan rules. Salons were divided by walls or curtains into separate women’s and men’s sections. The newlyweds were virtual strangers, their match arranged between families and their courtship limited to tightly chaperoned visits. After the ceremony, the bride was expected to move in with her husband’s family, for life. By religious law, he could divorce her at will, or marry up to three additional women. She had almost no rights at all. Even if she were abused or abandoned, it was considered a deep family shame if she sought a divorce, and a judge would admonish her to be more dutiful and reconcile.

On some levels, the departure of the Taliban brought new freedom and opportunity to women. Teachers and secretaries and hairdressers could return to work, girls could enroll in school again, and housewives could shop unveiled without risk of a beating from the religious police. In cities, fashionable women began wearing loose but smart black outfits with chic pumps. Women served as delegates to both Loya Jerga assemblies, the new constitution set aside parliamentary seats for women, and a female pediatrician in Kabul announced her candidacy for president.

But when it came to personal and sexual matters, political emancipation had no impact on a conservative Muslim society, where even educated urban girls did not expect to date or choose their mates. In Kabul, I became close friends with three women—a doctor, a teacher and a nurse—all articulate professionals who earned a good portion of their families’ income. Over three years, I knew them first as single, then engaged and finally married to grooms chosen by their families.

My three friends, chatty and opinionated about politics, were far too shy and embarrassed to talk with me about sex and marriage. When I delicately tried to ask how they felt about having someone else choose their spouse, or if they had any questions about their wedding night—I was 100 percent certain none had ever kissed a man—they blushed and shook their heads. “I don’t want to choose. That is not our tradition,” the nurse told me firmly.

Village life was even more impervious to change, with women rarely allowed to leave their family compounds. Many communities forced girls to leave school once they reached puberty, after which all contact with unrelated males was prohibited. During one visit to a village in the Shomali Plain, I met a woman with two daughters who had spent the Taliban years as refugees in Pakistan and recently moved home. The older girl, a bright 14-year-old, had completed sixth grade in Kabul, but now her world had shrunk to a farmyard with chickens to feed. I asked her if she missed class, and she nodded miserably. “If we left her in school, it would bring shame on us,” the mother said with a sigh.

For a western woman like me, life in Kabul grew increasingly comfortable. As the number of foreigners increased, I drew fewer stares and began to wear jeans with my blousy tunics. There were invitations to diplomatic and social functions, and for the first time since the end of Communist rule in 1992, liquor became easily available.

Yet despite the more relaxed atmosphere, Kabul was still no place for the pampered or faint of heart. My house was in an affluent district, but often there was no hot water, and sometimes no water at all; I took countless bucket baths on shivering mornings with tepid water from the city tap. Urban dust entered every crack, covered every surface with a fine gritty layer, turned my hair to straw and my skin to parchment. Just outside my door was a fetid obstacle course of drainage ditches and rarely collected garbage, which made walking a hazard and jogging out of the question.

Electricity was weak and erratic, although the municipal authorities set up a rationing system so residents could plan ahead; I regularly set my alarm for 5 a.m. so I could wash clothes before the 6 a.m. power cut. I became so accustomed to dim light that when I finally returned to the United States, I was shocked by how bright the rooms seemed.

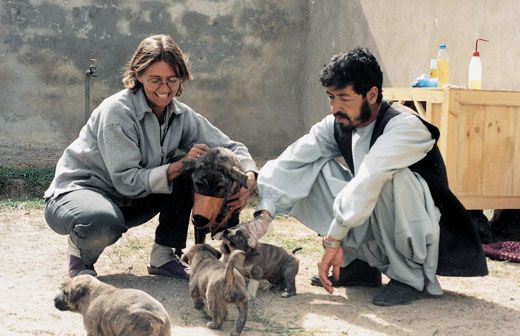

For all the stories I covered and the friends I made, what gave real meaning and purpose to my years in Kabul was something else entirely. I had always been an animal lover, and the city was full of emaciated, sickly stray dogs and cats. One by one they found their way into my house, and within a year it was functioning as a shelter. There were no small animal veterinary services—indeed, no culture of pets, unless one counted fighting dogs and roosters—so I treated the animals with pharmacy drugs and patient observation, and almost all of them bounced back.

Mr. Stumpy, a mangy cat whose hind leg had been crushed by a taxi and then amputated, hopped around the sun porch. Pak, a sturdy pup whose mother had been poisoned to death, buried bones in my backyard. Pshak Nau, a wild cat who lived over the garage, was gradually lured by canned tuna into domesticity. Honey, a pretty dog I bought for $10 from a man who was strangling her, refused to leave my side for days. Se Pai, a black kitten who was scavenging garbage on three legs, became a contented parlor cat after a terrible wound on his fourth leg healed.

One freezing night I found a dog so starved she could no longer walk, and I had to carry her home. I had no space left by then, but an Afghan acquaintance, an eccentric mathematician named Siddiq Afghan, said she was welcome to stay in his yard if she could reach accommodation with his flock of sheep. For an entire winter, I brought Dosty food twice a day, while she eyed the sheep and put on weight.

My happiest hours in Afghanistan were spent nursing these animals back to health, and my proudest accomplishment was opening a real animal shelter in a run-down house, which I refurbished and stocked and staffed so it would continue after I left. I also brought some of the animals back with me to America, a complicated and expensive ordeal in itself. Mr. Stumpy landed on a farm in Vermont, where his new owners soon sent me a photograph of an unrecognizably sleek, white creature. Dosty found a permanent home with a couple in Maryland, where she was last reported leaping halfway up oak trees to protect my friends from marauding squirrels. Pak, at this writing, is gnawing on an enormous bone in my backyard in Virginia.

Although I grew attached to Kabul, it was in the countryside that I experienced true generosity from people who had survived drought and war, hunger and disease. On a dozen trips, I forced myself to swallow greasy stews offered around a common pot—with bread serving as the only utensil—by families who could ill-afford an extra guest. And in remote villages, I met teachers who had neither chalk nor chairs nor texts, but who had devised ingenious ways to impart knowledge.

Over three years, I ventured into perhaps 20 provinces, usually in hasty pursuit of bad news. In Baghlan, where an earthquake toppled an entire village, I listened with my eyes closed to the sounds of a man digging and a woman wailing. In Oruzgan, where a U.S. gunship mistakenly bombed a wedding party, killing several dozen women and children, I contemplated a jumble of small plastic sandals left unclaimed at the entrance. In Logar, a weeping teacher showed me a two room schoolhouse for girls that had been torched at midnight. In Paktia, a dignified policeman twisted himself into a pretzel to show me how he had been abused in U.S. military custody.

During a trip to Nangarhar in the eastern part of the country, I was invited on a rollicking and uplifting adventure: a three-day field mission with U.S. military doctors and veterinarians. We straddled sheep to squirt deworming goo in their mouths, watched baby goats being born, and held stepladders so the vets could climb up to examine camels. We also glimpsed the brutal lives of Afghan nomads, who lived in filthy tents and traveled ancient grazing routes. A crippled girl was brought to us on a donkey for treatment; children were given the first toothbrushes they had ever seen; mothers asked for advice on how to stop having so many babies. By the time we were finished, hundreds of people were a little healthier and 10,000 animals had been vaccinated.

I also made numerous trips to poppy-growing areas, where the pretty but noxious crop, once nearly wiped out by the Taliban, made such a vigorous comeback that by late 2003 it accounted for more than half of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product and yielded as much as 75 percent of the world’s heroin. Drug trafficking began to spread as well, and U.N. experts warned that Afghanistan was in danger of becoming a “narco-state” like Colombia.

Along roads in Nangarhar and Helmand provinces, fields of emerald poppy shoots stretched in both directions. Children squatted busily along the rows, weeding the precious crop with small scythes. Village leaders showed me their hidden stores of poppy seeds, and illiterate farmers, sweating behind ox teams, paused to explain precisely why it made economic sense for them to plow under their wheat fields for a narcotic crop.

In March 2004, visiting a village in Helmand, I stopped to photograph a poppy field in scarlet blossom. Asmall girl in a bright blue dress ran up to my driver, beseeching him to appeal to me: “Please don’t destroy our poppies,” she said to him. “My uncle is getting married next month.” She could not have been older than 8, but she already knew that her family’s economic future—even its ability to pay for a wedding—depended on a crop that foreigners like me wanted to take away.

It was in Helmand also that I met Khair Mahmad, a toothless and partly deaf old man who had turned a corner of his simple stone house into a sanctuary of knowledge. The high school where he taught had been bombed years before and was still open to the sky; classes were held in U.N. tents. Mahmad invited us home to lunch, but we were pressed for time and declined. Then, a few miles on our way back to Kabul, our vehicle had a flat tire and we limped back to the area’s only gas station, which turned out to be near Mahmad’s house.

When we entered it, his family was eating a lunch of potatoes and eggs on the patio, and the old man leapt up to make room for us. Then he asked, a bit shyly, if we would like to see his study. I was impatient to leave, but assented out of courtesy. He led us up some stairs to a small room that seemed to glow with light. Every wall was covered with poems, Koranic verses and colored drawings of plants and animals. “Possessions are temporary but education is forever,” read one Islamic saying. Mahmad had perhaps a ninth-grade education, but he was the most knowledgeable man in his village, and for him it was a sacred responsibility. I felt humbled to have met him, and grateful for the flat tire that had led me to his secret shrine.

It was at such moments that I remembered why I was a journalist and why I had come to Afghanistan. It was in such places that I felt hope for the country’s future, despite the bleak statistics, the unaddressed human rights abuses, the seething ethnic rivalries, the widening cancer of corruption and drugs, and the looming struggle between the nation’s conservative Islamic soul and its compelling push to modernize.

When election day finally arrived, international attention focused on allegations of fraud at the polls, threats of Taliban sabotage and opposition sniping at Karzai’s advantages. In the end, as had been widely predicted, the president won handily over 17 rivals about whom most voters knew almost nothing. But at an important level, many Afghans who cast their ballots were not voting for an individual. They were voting for the right to choose their leaders, and for a system where men with guns did not decide their fates.

I had read all the dire reports; I knew things could still fall apart. Although the election was remarkably free of violence, a number of terrorist bombings and kidnappings struck the capital in the weeks that followed. But as I completed my tour of duty and prepared to return to the world of hot water and bright lights, smooth roads and electronic voting booths, I preferred to think of that chilly village schoolhouse and the face of that young farmer, poking a ballot into a plastic box and smiling to himself as he strode out of the room, wrapping his shawl a little tighter against the cold autumn wind.