In Haiti, the Art of Resilience

Within weeks of January’s devastating earthquake, Haiti’s surviving painters and sculptors were taking solace from their work

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Haiti-art-in-earthquake-rubble-631.jpg)

Six weeks had passed since a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti, killing 230,000 people and leaving more than 1.5 million others homeless. But the ground was still shaking in the nation’s rubble-strewn capital, Port-au-Prince, and 87-year-old Préfète Duffaut wasn’t taking any chances. One of the most prominent Haitian artists of the past 50 years was sleeping in a crude tent made of plastic sheeting and salvaged wood, fearful his earthquake-damaged house would collapse at any moment.

“Did you feel the tremors last night?” Duffaut asked.

Yes, I had felt the ground shake in my hotel room around 4:30 that morning. It was the second straight night of tremors, and I was feeling a bit stressed. But standing next to Duffaut, whose fantastical naive paintings I have admired for three decades, I resolved to put my anxieties on hold.

It was Duffaut, after all, who had lived through one of the most horrific natural disasters of modern times. Not only was he homeless in the poorest nation of the Western Hemisphere, his niece and nephew had died in the earthquake. Gone, too, were his next-door neighbors in Port-au-Prince. “Their house just completely collapsed,” Duffaut said. “Nine people were inside.”

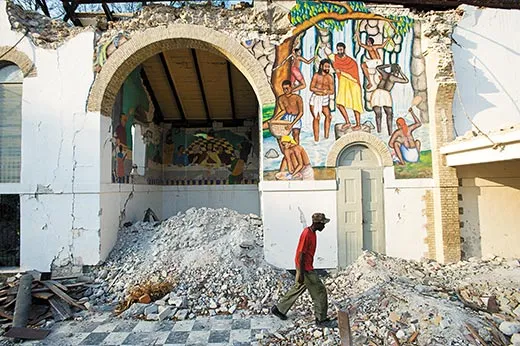

The diabolical 15- to 20-second earthquake on January 12 also stole a sizable chunk of Duffaut’s—and Haiti’s—artistic legacy. At least three artists, two gallery owners and an arts foundation director died. Thousands of paintings and sculptures—valued in the tens of millions of dollars—were destroyed or badly damaged in museums, galleries, collectors’ homes, government ministries and the National Palace. The celebrated biblical murals that Duffaut and other Haitian artists painted at Holy Trinity Cathedral in the early 1950s were now mostly rubble. The Haitian Art Museum at College St. Pierre, run by the Episcopal Church, was badly cracked. And the beloved Centre d’Art, the 66-year-old gallery and school that jump-started Haiti’s primitive art movement—making collectors out of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Bill and Hillary Clinton, the filmmaker Jonathan Demme and thousands of others—had crumbled. “The Centre d’Art is where I sold my first piece of art in the 1940s,” Duffaut said quietly, tugging on the white beard he had grown since the earthquake.

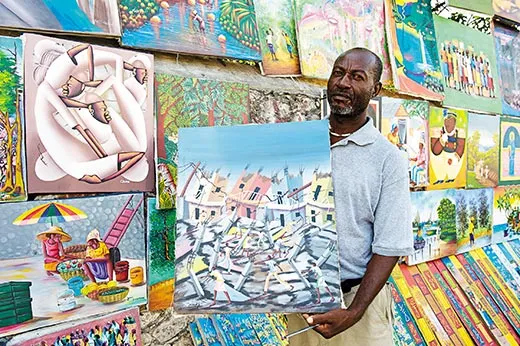

Duffaut disappeared from his tent and returned a few moments later with a painting that displayed one of his trademark imaginary villages, a rural landscape dominated by winding, gravity-defying mountain roads filled with tiny people, houses and churches. Then he retrieved another painting. And another. Suddenly, I was surrounded by six Duffauts—and all were for sale.

Standing beside his tent, which was covered by a tarpaulin stamped USAID, Duffaut flashed a satisfied grin.

“How much?” I asked.

“Four thousand dollars [each],” he said, suggesting the price local galleries would charge.

Not having more than $50 in my pocket, I had to pass. But I was delighted that Préfète Duffaut was open for business. “My future paintings will be inspired by this terrible tragedy,” he told me. “What I have seen on the streets has given me a lot of ideas and added a lot to my imagination.” There was an unmistakable look of hope in the old master’s eyes.

“Deye mon, gen mon,” a Haitian proverb, is Creole for “beyond the mountains, more mountains.”

Impossibly poor, surviving on less than $2 a day, most Haitians have made it their life’s work to climb over, under and around obstacles, be they killer hurricanes, food riots, endemic diseases, corrupt governments or the ghastly violence that appears whenever there is political upheaval. One victim of these all too frequent calamities has been Haitian culture: even before the earthquake, this French- and Creole-speaking Caribbean island nation of nearly ten million people did not have a publicly owned art museum or even a single movie theater.

Still, Haitian artists have proved astonishingly resilient, continuing to create, sell and survive through crisis after crisis. “The artists here have a different temperament,” Georges Nader Jr. told me in his fortress-like gallery in Pétionville, the once-affluent, hillside Port-au-Prince suburb. “When something bad happens, their imagination just seems to get better.” Nader’s family has been selling Haitian art since the 1960s.

The notion of making a living by creating and selling art first came to Haiti in the 1940s, when an American watercolorist named DeWitt Peters moved to Port-au-Prince. Peters, a conscientious objector to the world war then underway, took a job teaching English and was struck by the raw artistic expression he found at every turn—even on the local buses known as tap-taps.

He founded Centre d’Art in 1944 to organize and promote untrained artists, and within a few years, word had gone out that something special was happening in Haiti. During a visit to the center in 1945, André Breton, the French writer, poet and a leader of the cultural movement known as Surrealism, swooned over the work of a self-described houngan (voodoo priest) and womanizer named Hector Hyppolite, who often painted with chicken feathers. Hyppolite’s creations, on subjects ranging from still lifes to voodoo spirits to scantily clad women (presumed to be his mistresses), sold for a few dollars each. But, Breton wrote, “all carried the stamp of total authenticity.” Hyppolite died of a heart attack in 1948, three years after joining Centre d’Art and one year after his work was displayed at a triumphant (for Haiti as well as for him) United Nations-sponsored exhibition in Paris.

In the years that followed, the Haitian art market relied largely on the tourists who ventured to this Maryland-size nation, 700 or so miles from Miami, to savor its heady mélange of naive art, Creole food, smooth dark rum, hypnotic (though, at times, staged) voodoo ceremonies, high-energy carnivals and riotously colored bougainvillea. (Is it any wonder Haitian artists never lacked for inspiration?)

Though tourists largely shied away from Haiti in the 1960s, when self-declared president-for-life François “Papa Doc” Duvalier ruled through terror enforced by his personal army of Tonton Macoutes, they returned after his death in 1971, when his playboy son, Jean-Claude (known as “Baby Doc”), took charge.

I got my first glimpse of Haitian art when I interviewed Baby Doc in 1977. (His reign as president-for-life ended abruptly when he fled the country in 1986 for France, where he lives today at age 59 in Paris.) I was hooked the moment I bought my first painting, a $10 market scene done on a flour sack. And I was delighted that every painting, iron sculpture and sequined voodoo flag I carried home on subsequent trips gave me further insight into a culture that is a blend of West African, European, native Taíno and other homegrown influences.

Although some nicely done Haitian paintings could be bought for a few hundred dollars, the best works by early masters such as Hyppolite and Philomé Obin (a devout Protestant who painted scenes from Haitian history, the Bible and his family’s life) eventually commanded tens of thousands of dollars. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C. added Haitian primitives to their collections. And Haiti’s reputation as a tourist destination was reinforced by the eclectic parade of notables—from Barry Goldwater to Mick Jagger—who checked into the Hotel Oloffson, the creaky gingerbread retreat that is the model for the hotel in The Comedians, Graham Greene’s 1966 novel about Haiti.

Much of this exuberance faded in the early 1980s amid political strife and the dawn of the AIDS pandemic. U.S. officials classified Haitians as being among the four groups at highest risk for HIV infection. (The others were homosexuals, hemophiliacs and heroin addicts.) Some Haitian doctors called this designation unwarranted, even racist, but the perception stuck that a Haitian holiday was not worth the risk.

Though tourism waned, the galleries that sponsored Haitian painters and sculptors targeted sales to overseas collectors and the increasing numbers of journalists, development workers, special envoys, physicians, U.N. peacekeepers and others who found themselves in the country.

“Haitians are not a brooding people,” said gallery owner Toni Monnin, a Texan who moved to Haiti in the boom-time ’70s and married a local art dealer. “Their attitude is: ‘Let’s get on with it! Tomorrow is another day.’”

At the Gingerbread gallery in Pétionville, I was introduced to a 70-year-old sculptor who wore an expression of utter despondence. “I have no home. I have no income. And there are days when me and my family don’t eat,” Nacius Joseph told me. Looking for financial support, or at least a few words of encouragement, he was visiting the galleries that had bought and sold his work over the years.

Joseph told gallery owner Axelle Liautaud that his days as a woodcarver, creating figures such as La Sirene, the voodoo queen of the ocean, were over. “All my tools are broken,” he said. “I can’t work. All of my apprentices, the people who helped me, have left Port-au-Prince, gone to the provinces. I’m very discouraged. I have lost everything!”

“But don’t you love what you’re doing?” Liautaud asked.

Joseph nodded.

“Then you have to find a way to do it. This is a situation where you have to have some drive because everyone has problems.”

Joseph nodded again, but looked to be near tears.

Though the gallery owners were themselves hurting, many were handing out money and art supplies to keep the artists employed.

At her gallery a few blocks away, Monnin told me that in the days following the quake she distributed $14,000 to more than 40 artists. “Right after the earthquake, they simply needed money to buy food,” she said. “You know, 90 percent of the artists I work with lost their homes.”

Jean-Emmanuel “Mannu” El Saieh, whose late father, Issa, was one of the earliest promoters of Haitian art, was paying a young painter’s medical bills. “I just talked to him on the phone, and you don’t have to be a doctor to know he’s still suffering from shock,” El Saieh said at his gallery, just up a rutted road from the Oloffson hotel, which survived the quake.

Though most of the artists I encountered had become homeless, they did not consider themselves luckless. They were alive, after all, and aware that the tremblement de terre had killed many of their friends and colleagues, such as the octogenarian owners of the Rainbow Gallery, Carmel and Cavour Delatour; Raoul Mathieu, a painter; Destimare Pierre Marie Isnel (a.k.a. Louco), a sculptor who worked with discarded objects in the downtown Grand Rue slum; and Flores “Flo” McGarrell, an American artist and film director who in 2008 moved to Jacmel (a town with splendid French colonial architecture, some of which survived the quake) to head up a foundation that supported local artists.

The day I arrived in Port-au-Prince, I heard rumors of another possible casualty—Alix Roy, a reclusive, 79-year-old painter who had been missing since January 12. I knew Roy’s work well: he painted humorous scenes from Haitian life, often chubby kids dressed up as adults in elaborate costumes, some wearing oversize sunglasses, others balancing outrageously large fruits on their heads. Although he was a loner, Roy was an adventurous sort who had also lived in New York, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.

A few nights later, Nader called my room at Le Plaza (one of the few hotels in the capital open for business) with some grim news. Not only had Roy died in the rubble of the gritty downtown hotel where he lived, his remains were still buried there, six weeks later. “I’m trying to find someone from the government to pick him up,” Nader said. “That’s the least the Haitian government can do for one of its best artists.”

The next day, Nader introduced me to Roy’s sister, a retired kindergarten director in Pétionville. Marléne Roy Etienne, 76, told me her older brother had rented a room on the top floor of the hotel so he could look down on the street for inspiration.

“I went to look for him after the earthquake but couldn’t even find where the hotel had been because the entire street—Rue des Césars—was rubble,” she said. “So I stood in front of the rubble where I thought Alix might be and said a prayer.”

Etienne’s eyes teared when Nader assured her he would continue pressing government officials to retrieve her brother’s remains.

“This is hard,” she said, reaching for a handkerchief. “This is really hard.”

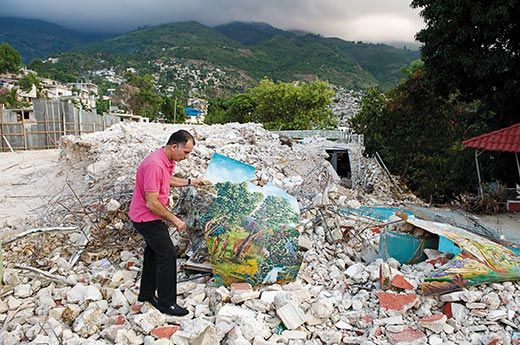

Nader had been through some challenging times himself. Although he had not lost any family members, and his gallery in Pétionville was intact, the 32-room house where his parents lived, and where his father, Georges S. Nader, had built a gallery that contained perhaps the largest collection of Haitian art anywhere, had crumbled.

The son of Lebanese immigrants, the elder Nader was long considered one of Haiti’s best-known and most successful art dealers, having established relationships with hundreds of artists since he opened a gallery downtown in 1966. He moved into the mansion in the hillside Croix-Desprez neighborhood a few years later and, in addition to the gallery, built a museum that showcased many of Haiti’s finest artists, including Hyppolite, Obin, Rigaud Benoit and Castera Bazile. When he retired a few years ago, Nader turned over the gallery and museum to his son John.

The elder Nader had been taking a nap with his wife when the quake struck at 4:53 p.m. “We were rescued within ten minutes because our bedroom did not collapse,” he told me. What Nader saw when he was led outside was horrifying. His collection had become a hideous pile of debris with thousands of paintings and sculptures buried under giant blocks of concrete.

“My life’s work is gone,” Nader, 78, told me by telephone from his second home in Miami, where he has been living since the quake. Nader said he never bought insurance for his collection, which the family estimated to be worth more than $20 million.

With the rainy season approaching, Nader’s sons hired a dozen men to pick, shovel and jackhammer their way through the debris, looking for anything that could be salvaged.

“We had 12,000 to 15,000 paintings here,” Georges Nader Jr. told me as we stomped through the sprawling heap, which reminded me of a bombed-out village from a World War II documentary. “We’ve recovered about 3,000 paintings and about 1,800 of those are damaged. Some other paintings were taken by looters in the first days after the earthquake.”

Back at his gallery in Pétionville, Nader showed me a Hyppolite still life he had recovered. I recognized it, having admired the painting in 2009 at a retrospective at the Organization of American States’ Art Museum of the Americas in Washington. But the 20- by 20-inch painting was now broken into eight pieces. “This will be restored by a professional,” Nader said. “We have begun restoring the most important paintings we have recovered.”

I heard other echoes of cautious optimism as I visited cultural sites across Port-au-Prince. A subterranean, government-run historical museum that contained some important paintings and artifacts had survived. So did a private voodoo and Taíno museum in Mariani (near the quake’s epicenter) and an ethnographic collection in Pétionville. People associated with the destroyed Holy Trinity Cathedral and Centre d’Art, as well as the Episcopal Church’s structurally feeble Haitian Art Museum, assured me that these institutions will be rebuilt. But no one could say how or when.

The United Nations has announced that 59 countries and international organizations have pledged $9.9 billion as “the down payment Haiti needs for wholesale national renewal.” But there’s no word on how much of that money, if any, will ever reach the cultural sector.

“We deeply believe that Haitians living abroad can help us with the funds,” said Henry Jolibois, an artist and architect who is a technical consultant to the Haitian prime minister’s office. “For the rest, we must convince other entities in the world to participate, such as the museums and private collectors who have huge Haitian naive painting collections.”

At the Holy Trinity Cathedral 14 murals had long offered a distinctively Haitian take on biblical events. My favorite was the Marriage at Cana by Wilson Bigaud, a painter who excelled at glimpses into everyday Haitian life—cockfights, market vendors, baptismal parties, rara band parades. While some European artists portrayed the biblical event at which Christ turned water into wine as being rather formal, Bigaud’s Cana was a decidedly casual affair with a pig, rooster and two Haitian drummers looking on. (Bigaud died this past March 22 at age 79.)

“That Marriage at Cana mural was very controversial,” Haiti’s Episcopal bishop, Jean Zaché Duracin, told me in his Pétionville office. “In the ’40s and ’50s many Episcopalians left the church in Haiti and became Methodists because they didn’t want these murals at the cathedral. They said, ‘Why? Why is there a pig in the painting?’ They didn’t understand there was a part of Haitian culture in these murals.”

Duracin told me it took him three days to gather the emotional strength to visit Holy Trinity. “This is a great loss, not only for the Episcopal church but for art worldwide,” he said.

Visiting the site myself one morning, I saw two murals that were more or less intact—The Baptism of Our Lord by Castera Bazile and Philomé Obin’s Last Supper. (A third mural, Native Street Procession, by Duffaut, has survived, says former Smithsonian Institution conservator Stephanie Hornbeck, but others were destroyed.)

At the Haitian Art Museum, chunks of concrete had fallen on some of the 100 paintings on exhibit. I spotted one of Duffaut’s oldest, largest and finest imaginary village paintings propped against a wall. A huge piece was missing from the bottom. A museum employee told me the piece had not been found. As I left, I reminded myself that although thousands of paintings had been destroyed in Haiti, thousands of others survived, and many are outside the country in private collections and institutions, including the Waterloo Center for the Arts in Iowa and the Milwaukee Art Museum, which have important collections of Haitian art. I also took comfort from conversations I had had with artists like Duffaut, who were already looking beyond the next mountain.

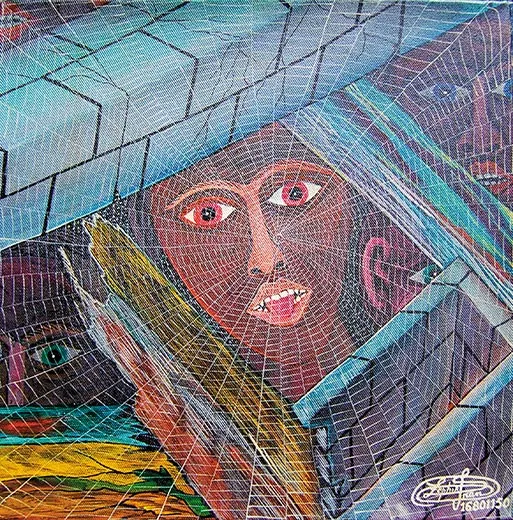

No one displays Haiti’s artistic resolve more than Frantz Zéphirin, a gregarious 41-year-old painter, houngan and father of 12, whose imagination is as large as his girth.

“I’m very lucky to be alive,” Zéphirin told me late one afternoon in the Monnin gallery, where he was putting the finishing touches on his tenth painting since the quake. “I was in a bar on the afternoon of the earthquake, having a beer. But I decided to leave the bar when people starting talking about politics. And I’m glad I left. The earthquake came just one minute later, and 40 people died inside that bar.”

Zéphirin said he walked several hours, at times climbing over corpses, to get to his house. “That’s where I learned that my stepmother and five of my cousins had died,” he said. But his pregnant girlfriend was alive; so were his children.

“That night, I decided I had to paint,” Zéphirin said. “So I took my candle and went to my studio on the beach. I saw a lot of death on the way. I stayed up drinking beer and painting all night. I wanted to paint something for the next generation, so they can know just what I had seen.”

Zéphirin led me to the room in the gallery where his earthquake paintings were hung. One shows a rally by several fully clothed skeletons carrying a placard written in English: “We need shelters, clothes, condoms and more. Please help.”

“I’ll do more paintings like these,” Zéphirin said. “Each day 20 ideas for paintings pass in my head, but I don’t have enough hands to make all of them.” (Smithsonian commissioned the artist to create the painting that appears on the cover of this magazine. It depicts the devastated island nation with grave markers, bags of aid money and birds of mythic dimensions delivering flowers and gifts, such as “justice” and “health.”) In March, Zéphirin accepted an invitation to show his work in Germany. And two months later, he would head to Philadelphia for a one-man show, titled “Art and Resilience,” at the Indigo Arts Gallery.

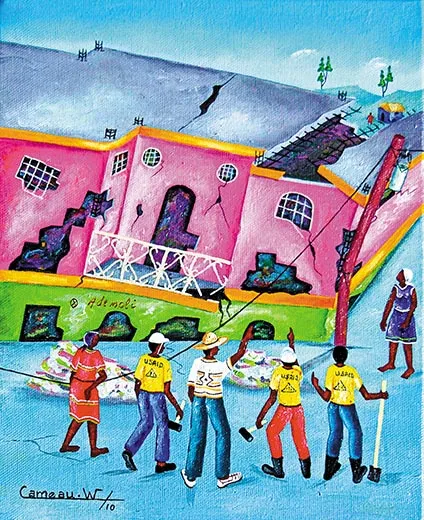

A few miles up a mountain road from Pétionville, one of Haiti’s most celebrated contemporary artists, Philippe Dodard, was preparing to bring more than a dozen earthquake-inspired paintings to Arte Américas, an annual fair in Miami Beach. Dodard showed me a rather chilling black-and-white acrylic that was inspired by the memory of a friend who perished in an office building. “I’m calling this painting Trapped in the Dark,” he said.

I have no idea how Dodard, a debonair man from Haiti’s elite class whose paintings and sculptures confirm his passion for his country’s voodoo and Taíno cultures, had found time to paint. He told me he had lost several friends and family members in the quake, as well as the headquarters of the foundation he helped create in the mid-1990s to promote culture among Haitian youth. And he was busily involved in a project to convert a fleet of school buses—donated by the neighboring Dominican Republic—into mobile classrooms for displaced students.

Like Zéphirin, Dodard seemed determined to work through his grief with a paintbrush in hand. “How can I continue living after one of the biggest natural disasters in the history of the world? I can’t,” he wrote in the inscription that would appear next to his paintings at the Miami Beach show. “Instead I use art to express the deep change that I see around and inside me.”

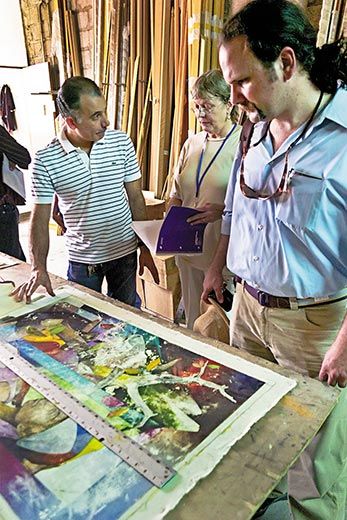

For the Haitian art community, more hopeful news was on the way. In May, the Smithsonian Institution launched an effort to help restore damaged Haitian treasures. Led by Richard Kurin, under secretary for history, art and culture, and working with private and other public organizations, the Institution established a “cultural recovery center” at the former headquarters of the U.N. Development Program near Port-au-Prince.

“It’s not every day at the Smithsonian that you actually get to help save a culture,” Kurin says. “And that’s what we’re doing in Haiti.”

On June 12, after months of preparation, conservators slipped on their gloves in the Haitian capital and got to work. “Today was a very exciting day for...conservators, we got objects into the lab! Woo hoo!” the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Hugh Shockey enthused on the museum’s Facebook page.

Kurin sounded equally pumped. “The first paintings we brought in were painted by Hector Hyppolite. So we were restoring those on Sunday,” he told me a week later. “Then on Monday our conservator from the American Art Museum was restoring Taíno, pre-Colombian artifacts. Then on Tuesday the paper conservator was dealing with documents dating from the era of the Haitian struggle for independence. And then the next day we were literally on the scaffolding at the Episcopal cathedral, figuring out how we’re going to preserve the three murals that survived.”

The task undertaken by the Smithsonian and a long list of partners and supporters that includes the Haitian Ministry of Culture and Communication, the International Blue Shield, the Port-au-Prince-based foundation FOKAL and the American Institute for Conservation seemed daunting; thousands of objects need restoration.

Kurin said the coalition will train several dozen Haitian conservators to take over when the Smithsonian bows out in November 2011. “This will be a generation-long process in which Haitians do this themselves,” he said, adding that he hopes donations from the international community will keep the project alive.

Across the United States, institutions such as the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, galleries such as Indigo Arts in Philadelphia and Haitian-Americans such as Miami-based artist Edouard Duval Carrié were organizing sales and fund-raisers. And more Haitian artists were on the move—some to a three-month residency program sponsored by a gallery in Kingston, Jamaica, others to a biennial exhibition in Dakar, Senegal.

Préfète Duffaut stayed in Haiti. But during an afternoon we spent together he seemed energized and, though Holy Trinity was mostly a pile of rubble, he was making plans for a new mural. “And my mural in the new cathedral will be better than the old ones,” he promised.

Meanwhile, Duffaut had just finished a painting of a star he saw while sitting outside his tent one night. “I’m calling this painting The Star of Haiti,” he said. “You see, I want all of my paintings to send a message.”

The painting showed one of Duffaut’s imaginary villages inside a giant star that was hovering like a spaceship over the Haitian landscape. There were mountains in the painting. And people climbing. Before bidding the old master farewell, I asked him what message he wanted this painting to send.

“My message is simple,” he said without a moment’s hesitation. “Haiti will be back.”

Bill Brubaker, formerly a Washington Post writer, has long followed Haitian art. In her photographs and books, Alison Wright focuses on cultures and humanitarian efforts.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.