Livin’ on the Dock of the Bay

From the Beats to CEOs, the residents of Sausalito’s houseboat community cherish their history and their neighbors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sausalito-house-boats-community-631.jpg)

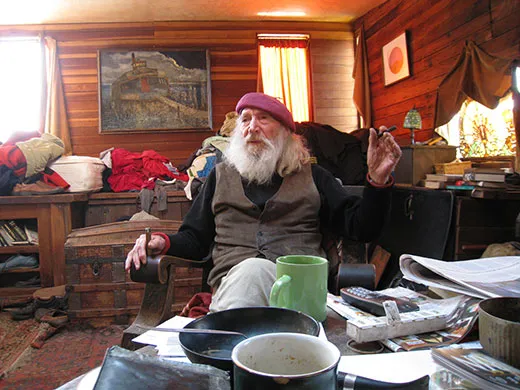

Larry Moyer faced me across a cluttered wooden table in the sitting room of the houseboat Evil Eye. He was wearing a brown suede vest. His eyes gleamed benevolently beneath a purple beret. A white beard billowed down his neck, thick as the smoke from his narrow black cigar.

Though Shel Silverstein has been gone 13 years, his spirit seemed to be with us as we relaxed in his former houseboat. Moyer—a filmmaker, painter and photographer who now stewards the Evil Eye—traveled with The Giving Tree author for years, when they worked together as a writer/photographer team for Playboy during the magazine’s first two decades. That was a while ago; Moyer turned 88 earlier this year. But he clearly recalls the story of how he and Silverstein arrived here, in Sausalito’s legendary houseboat community, 45 years ago.

“In February 1967, when I lived in a Greenwich Village apartment, a friend sent me a birthday present: A woman named Nicki knocked at my door, delivering a hot pastrami sandwich and a pickle.” Having just returned from San Francisco, Nicki suggested that the blossoming Haight-Ashbury scene would make a great feature for Playboy.

“So Shel and I got sent out West. We spent three months in the Haight. While we were there, we visited a friend of Nicki’s—rock guitarist Dino Valenti—here on the Sausalito waterfront.”

Moyer and Silverstein took in the scene. “There were a few hundred boats. It was total freedom. The music, the people, the architecture, the nudity—all we could say was, ‘Wow!’ So Shel bought a boat, and I bought a boat. And that was that.”

Today, 245 floating homes nose into the five docks at Sausalito’s Waldo Point Harbor. The scene’s a bit less wild. Pilots, physicians and executives now share the Richardson Bay waterfront with artists, writers and inveterate sea salts. Some of the houseboats are simple and unpresuming, enlivened with plaster gnomes and patrolled by tomcats. Others—custom-built dream homes valued upwards of $1.3 million—have appeared in films and magazines. And though the characters are as fascinating as they were in the ’60s, there’s a notable decline in public nudity.

Walking the docks in the early morning is a calming experience: an escape into a realm of broad light, subtle motion and seabird calls.

The variety of houseboats is astonishing. Though they’re physically close, the architectural styles are worlds apart. Each reflects the imagination (and/or means) of its owner. Some look like shotgun shacks, others like pagodas, bungalows or Victorians. Most defy a category altogether. There’s the prominent Owl, with its horned wooden tower and wide-eyed windows; the SS Maggie, a former 1889 steam schooner, now appointed like Thurston Howell III’s retreat; and the Dragon Boat, with its etched glass and Asian statuary. Quite a few look like what they are: former Navy ships, reimagined as private homes. They rise up from barges, tugboats, World War II landing craft, even subchasers. A couple, including the Evil Eye, are built atop balloon barges, ships whose lofted cables were designed to snare kamikaze aircraft.

Beyond the docks, a few lone houseboats rock in the open bay. These are the “anchor-outs”: solitary water-dwellers who rely on row boats and high tides to keep their homes provisioned. One of them is Moyer’s painting studio. The others belong to more elusive souls. They lend the neighborhood an air of mystery.

Larry Moyer’s arrival story isn’t typical, but his enthusiasm for the place wasn’t unusual. For certain people, life on the water has a magnetic appeal. Even today—as the harbor prepares for a makeover that will erase much of its storied past—the docks offer a sense of community and an otherworldly ambiance found almost nowhere else.

The houseboat era began in the late 19th century, when well-to-do San Franciscans kept “arks”—floating holiday homes—on local rivers and deltas. After the 1906 earthquake, some became semi-permanent refuges.

But the modern branch of Sausalito’s houseboat evolution began after World War II. Marinship Corporation, on Richardson Bay, operated a facility for building Liberty ships: vital transports that carried cargo into the Pacific theater. More than 20,000 people worked intensely on that effort. When the war ended, though, Marinship ceased operations almost overnight. Tons of wood, metal and scrap were left behind. Richardson Bay turned into an aquatic salvage yard, a tidal pool of possibilities.

Ecologist and Whole Earth Catalog creator Stewart Brand, who has lived on the tugboat Mirene since 1982, tells how “the former shipyard became a semi-outlaw area and riffraff moved in—floated in.” During the 1950s and ‘60s, as the Beats gave way to the hippies, the chance to construct rent-free homes out of abandoned boats and flotsam was a siren song that drew a spectrum of characters. Some were working artists, like Moyer, who bought and improved old boats. There were also musicians, drug dealers, misfits and other fringe-dwellers. The waterfront swelled into a community of squatters who, as Brand puts it, “had more nerve than money.”

“People lived here because they could afford it,” agreed Moyer. “You could find an old lifeboat hull to build on, and there was always stuff to recycle because of the shipyards. Whatever you wanted. If you needed a beam of wood ten feet long by one foot wide, one would come floating up.” Through the early 1970s, the Sausalito houseboat scene was a sort of anarchist commune. The heart and soul was the Charles Van Damme, a derelict 1916 ferry that served as community center, restaurant and rumpus room.

Shel Silverstein wasn’t the only celebrity in the mix. Artist Jean Varda shared the ferry Vallejo with Buddhist writer/philosopher Alan Watts. In 1967 Otis Redding wrote his hit “Dock of the Bay” on a Sausalito houseboat (which one, exactly, is still a matter of controversy). Actors Sterling Hayden, Rip Torn and Geraldine Page all kept floating homes. The roll call would in time include Brand, author Anne Lamott, Bill Cosby and environmentalist Paul Hawken.

But the good times didn’t last. A paradise for some, the chaotic community—with its wacky architecture, filched electricity and untreated sewage—was an eyesore to others. Local developers set their sites on revamping the Sausalito waterfront, with its dizzying real estate potential.

At the park’s edge stand the antique paddle wheel and steam stack of the Charles Van Damme, all that remain of the now bulldozed ferry. Doug Storms, a commercial diver who has lived on the waterfront since 1986, led me past a small waterfront garden.

“In the 1960s and early ‘70s, there was the classic conflict between the haves and have-nots,” said the sinewy Storms. "Between the developers and the local community, many who were living here rent-free."

The result was a long and ugly battle known as “The Houseboat Wars.” Dramatized in a folksy 1974 film (Last Free Ride), the battle pit the waterfront’s squatter community against the combined might of the local police, city council and Coast Guard.

Ultimately, the developers more or less prevailed. Most of the houseboats were relocated along a series of five new docks, built by the Waldo Point Harbor company. Their electricity and sewage lines are now up to code. The process of gentrification on the new docks has been steady and not altogether unwelcome. Though they bristle at the monthly slip fees, many old-timers have seen the value of their floating homes skyrocket.

But a small community of mavericks, including Storms, refused to be bullied. The “Gates Co-op,” as their dock is called, remains a throwback to the old days. With its tangles of electrical wire, wobbly walkways and erratic sanitation, it looks more like Katmandu than California.

And so it will stay until July, when Waldo Point Harbor is supposed to begin a long-delayed reconfiguration process. Along with many other “improvements” (depending on your point of view), the funky co-op will be dismantled, and its residents relocated in subsidized houseboats at new or existing berths.

Will it actually happen? No one knows. The obstacles to getting anything done on the waterfront seem endless. There’s a much-loved example of this phenomenon, known simply as “the pickleweed story.”

Some years ago, the story goes, a goat lived at the co-op docks. It grazed freely, cropping all the nearby pickleweed. Then, as now, the parking lots near the docks flooded at high tides, sometimes destroying cars. The locals had a permit—approved by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—to raise the parking lots, using landfill.

As happens every few years, the Army colonel in charge was rotated out. Around the same time, the goat died—and the pickleweed grew back. When the new colonel toured the area, he shook his head. “Pickleweed means these are wetlands," he said. “And you’re not allowed to build on a wetland.” And so, for the loss of a goat, went the permit.

“Every year they say they're going to do the reconfiguration,” Joe Tate informed me with a grin. “But nothing has changed here very much—not since they bulldozed the Charles Van Damme back in 1983.”

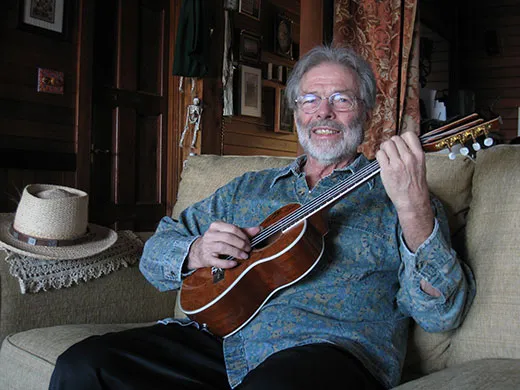

The scrappy Tate, now 72, arrived here from St. Louis in 1964. He was the rebel leader during the Houseboat Wars, and lead singer/guitarist for the legendary RedLegs, the waterfront’s homegrown rock band. (Their current incarnation, The Gaters, plays most Saturday nights at Sausalito’s No-Name Bar.) Tate grew up along the Mississippi, where his father was a riverboat pilot. His boating and building skills—and reckless good humor—are evident to anyone who’s seen Last Free Ride.

“I’m known as the ‘King of the Waterfront,’ and I don't know why.” Tate conceded. “I did lead the charge against the developers—but in 1976, in the middle of the whole thing, I sailed away with my family.” Tate, weary of the constant struggle, headed south. “We went to Costa Rica, to Mexico and to Hawaii. I thought we were going to find something better.” He shrugged. “We didn’t.”

Tate moved back to the waterfront in 1979. He now lives on the Becky Thatcher: the same houseboat (albeit renovated) that Larry Moyer bought in 1967 for $1,000. From his living room window Tate can look onto a broad channel, flanked by floating homes. “They say they’re going to fill all that up with boats from the co-op. I’m not looking forward to that,” he sighed. “But a lot of the people they’re going to bring over are old friends of mine.”

I asked Tate if he feels that, in retrospect, the Houseboat Wars were won or lost.

“We didn't lose completely,” he said. “I mean, they were going to run us out of here!” By fighting back, the Gates Co-op people reached an agreement with the developers; those who moved onto the Waldo Point docks got 20-year leases. “So we’ve settled into a steady state of exploitation,” the former rebel sighed, “where the rent goes up every year.”

“But we’re managing,” he allowed cheerfully. “With all the old ‘Gaters’ and the new people, too. After all these years, we’re still a community.”

There are pros and cons to houseboat living, but Tate hit the nail on the head. One afternoon, while exploring the docks with a San Francisco physician named Paul Boutigny, I understood the importance of community to this enclave of Sausalito.

Boutigny and his wife are new arrivals on Main Dock, having moved there from the Haight in 2010. Young and affluent, they represent the oft-maligned trend toward gentrification. Still, they’ve been welcomed by their neighbors. Sharing a meal with Boutigny, who’s clearly enchanted by his new neighborhood, it’s easy to understand why.

“Everybody who moves here brings something different,” he said passionately. “And everybody, rich or poor, is part of the waterfront—from the anchor-outs to the huge houseboats at the ends of the docks. Everybody’s connected by one fact: We live on the water. Now that doesn’t mean that we all know each other. But there’s a commonality we all share.”

“There are people on welfare, there are millionaires, there are outstanding artists, there are computer whizzes,” agreed Henry Baer, a retired dentist on dock South 40. “I’ve lived in apartment buildings with 20 units; maybe you know your next-door neighbor, because you meet them at the mailbox. Here, walking to and from your boat, you meet half the people on the dock. Yes, we all come from diverse economic backgrounds. But when there’s a problem, everybody comes out and helps one another.”

Day after day, on dock after dock, I heard confirming stories: people going out in kayaks, checking their neighbors’ moorings before an El Niño storm; houseboats rescued from fire or flood, even while the owners were on another continent. There’s an unwritten code of cooperation, tempered by a hard-wired respect for privacy.

“It’s not something we indoctrinate people about,” said Larry Clinton, president of the Sausalito Historical Society and a houseboat resident since 1982. “We don’t put people through an orientation when they move here. They just get it. It’s the most amazing phenomenon of self-help in a community that I’ve encountered.”

Another big perk is that the community, as Clinton pointed out, is not limited to humans. “The fish and birds change from season to season—even with changes of the tide, because some birds prefer low tide. The egrets and herons come out then and peck thru the mud.”

A sea lion swam past, glancing briefly at its bipedal neighbors. Clinton laughed. “My wife says that looking out our glass doors is like having the Nature Channel on all day long.”

Not all the creatures are as benign. At low tide raccoons can invade houseboats through open windows, causing culinary mayhem. And in the summer of 1986, Richardson Bay residents were bedeviled by an eerie thrumming that sounded like a Russian sub, or an alien spaceship. A marine biologist was called in. He discovered that the noise came from creatures called humming toadfish, which attached themselves to the hulls during mating season. (Instead of fighting the creatures, the community named an annual festival after them.)

What else goes wrong? Well, the parking lots still flood at high tide. And carrying a load of groceries between car and boat is no fun in the driving rain.

Sometimes, just the notion of a “floating home” is enough to panic newcomers. Henry and Renée Baer have lived on the “Train Wreck,” one of the most remarkable dwellings on the Sausalito docks, since 1993. Built by architect Keith Emons around the bisected carriage of a 1900 Pullman car, it’s a masterpiece—and a monumental investment.

“In the early days, every time we came back from a trip I would run up the dock in a panic,” Renée confessed, “until I could see our roof. Then I’d breath a sigh of relief, because I knew it was still there. It hadn’t sunk, or floated out to sea, with all my clothes and everything gone.”

Realistically, though, houseboat owners have fewer natural catastrophes to contend with than their friends in San Francisco or the Oakland Hills.

“We don’t care about earthquakes here,” Stewart Brand pointed out as we shared lunch aboard Mirene. “Or wildfire. We don’t even care about sea level rise very much…yet.” (Of all the houseboats, I learned, Mirene is the only seaworthy vessel. The docks are more like a trailer park than an RV campground, with most of the houseboats encased in concrete hulls. It’s a Faustian bargain: They’re protected from rot and ocean organisms at the price of immobility.)

“And I was surprised to discover,” he continued, “that the absence of trees is not a bug, its a feature. Leaves do not fall on your deck. Trees do not fall on you. And if you want to see the sun, its always there.”

South 40, “A” Dock and Liberty; Main and Issaquah; each of the five-plus Waldo Point docks feels like a tribal settlement, with bloodlines extending across the waterfront. All have a distinct personality and a clannish pride. Some are known for their lush plantings, others for their oddball sculptures, cocktail parties, feral cats, or flights of architecture.

South 40, where I spent several stormy nights, won my fealty. It hosts some of the quirkiest houseboats, including the majestic old Owl, the Train Wreck, the Becky Thatcher and the Ameer, the only original 19th-century ark still afloat on Richardson Bay (and the former home of beloved Sausalito writer and cartoonist Phil Frank).

Though every dock is different, together they’re a subculture. It’s not easy to categorize the people who gravitate toward houseboats—but fascination with the ever-changing marine environment is a common denominator.

Cyra McFadden, a writer and editor whose 1977 The Serial peeled the veneer off the Marin social scene, has lived at Waldo Point for 14 years. Her spacious home, with its fireplace, framed artworks and picture-book view of Mount Tamalpais, “is really a town house on a barge,” McFadden acknowledged. “It doesn’t feel particularly like a boat. But it moves—ever so slightly—and the view will change through the window. Or I’ll be at the table having breakfast, suddenly aware that the wind is coming from a different direction. I love the creaking noises, and the bubbling that the boat makes when the tide comes. I love the fact that this house is alive.”

“I think people come here because they don’t want to feel boxed in,” added Susan Neri, a portrait artist who lives aboard the small but cozy landing craft Lonestar. “It’s an ecosystem where the water meets the land, and nothing is quite the same from day to day. There’s also the reflective quality of living here. It may come from the reflections that we live with every day, off the bay and the boats, in the house and all around us.” She looks out her window, a kinetic view of clouds and gulls. “For me, its a bit of living on the edge,” she said. “It’s magical. I can’t imagine living on the land again.”

My final afternoon, I stop by the Evil Eye for a word with Larry Moyer. The waterfront sage greets me warmly and lights up a cigar.

“I’m a bit overwhelmed,” I tell him. “I’ve heard more stories than I can possibly absorb. But I’m still searching for a through-line; something to tie it all together.”

Moyer nods. A war-torn tomcat curls up in his lap. “Look behind you,” he says, “and weep.”

I turn around. There’s a bookshelf above his desk, overflowing with film reels, videotapes and cassettes. During his decades as a photographer and artist, Moyer has shot hundreds of hours of film: scenes of the houseboats, the community, the music, the bawdy shenanigans on the docks. I turn back to him, amazed by this treasure-trove of footage. Moyer grins and shrugs his shoulders.

“I’ve lived here 45 years,” he says. “And I don’t have a through-line!"

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.