Pilgrims’ Progress

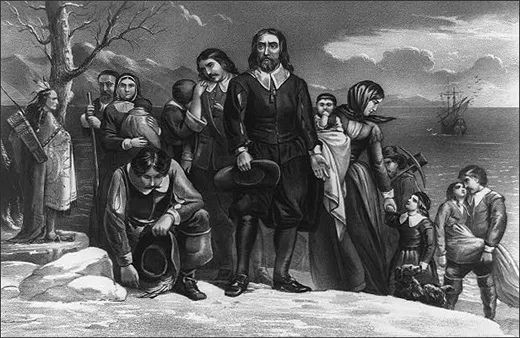

We retrace the travels of the ragtag group that founded Plymouth Colony and gave us Thanksgiving

On an autumn night in 1607, a furtive group of men, women and children set off in a relay of small boats from the English village of Scrooby, in pursuit of the immigrant's oldest dream, a fresh start in another country. These refugees, who would number no more than 50 or 60, we know today as Pilgrims. In their day, they were called Separatists. Whatever the label, they must have felt a mixture of fear and hope as they approached the dimly lit creek, near the Lincolnshire port of Boston, where they would steal aboard a ship, turn their backs on a tumultuous period of the Reformation in England and head across the North Sea to the Netherlands.

There, at least, they would have a chance to build new lives, to worship as they chose and to avoid the fate of fellow Separatists like John Penry, Henry Barrow and John Greenwood, who had been hanged for their religious beliefs in 1593. Like the band of travelers fleeing that night, religious nonconformists were seen as a threat to the Church of England and its supreme ruler, King James I. James' cousin, Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603), had made concerted efforts to reform the church after Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic faith in the 1530s. But as the 17th century got under way at the end of her long reign, many still believed that the new church had done too little to distinguish itself from the old one in Rome.

In the view of these reformers, the Church of England needed to simplify its rituals, which still closely resembled Catholic practices, reduce the influence of the clerical hierarchy and bring the church's doctrines into closer alignment with New Testament principles. There was also a problem, some of them felt, with having the king as the head of both church and state, an unhealthy concentration of temporal and ecclesiastical power.

These Church of England reformers came to be known as Puritans, for their insistence on further purification of established doctrine and ceremony. More radical were the Separatists, those who split off from the mother church to form independent congregations, from whose ranks would come the Baptists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and other Protestant denominations. The first wave of Separatist pioneers—that little band of believers sneaking away from England in 1607—would eventually be known as Pilgrims. The label, which came into use in the late 18th century, appears in William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation.

They were led by a group of radical pastors who, challenging the authority of the Church of England, established a network of secret religious congregations in the countryside around Scrooby. Two of their members, William Brewster and William Bradford, would go on to exert a profound influence on American history as leaders of the colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts, the first permanent European settlement in New England and the first to embrace rule by majority vote.

For the moment, though, they were fugitives, inner exiles in a country that did not want their brand of Protestantism. If caught, they faced harassment, heavy fines and imprisonment.

Beyond a few tantalizing details about the leaders Brewster and Bradford, we know very little about these English men and women who formed the vanguard of the Pilgrim's arrival in the New World—not even what they looked like. Only one, Edward Winslow, who became the third governor of Plymouth Colony in 1633, ever sat for his portrait, in 1651. We do know that they did not dress in black and white and wear stovepipe hats as the Puritans did. They dressed in earth tones—the green, brown and russet corduroy typical of the English countryside. And, while they were certainly religious, they could also be spiteful, vindictive and petty—as well as honest, upright and courageous, all part of the DNA they would bequeath to their adopted homeland.

To find out more about these pioneering Englishmen, I set off from my home in Herefordshire and headed north to Scrooby, now a nondescript hamlet set in a bucolic landscape of red brick farmhouses and gently sloping fields. The roadsides were choked with daffodils. Tractors chugged through rich fields with their wagons full of seed potatoes. Unlike later waves of immigrants to the United States, the Pilgrims came from a prosperous country, not as refugees escaping rural poverty.

The English do not make much of their Pilgrim heritage. "It's not our story," a former museum curator, Malcolm Dolby, told me. "These aren't our heroes." Nonetheless, Scrooby has made at least one concession to its departed predecessors: the Pilgrim Fathers pub, a low, whitewashed building, right by the main road. The bar used to be called the Saracen's Head but got a face-lift and a change of name in 1969 to accommodate American tourists searching their roots. A few yards from the pub, I found St. Wilfrid's church, where William Brewster, who would become the spiritual leader of Plymouth Colony, once worshiped. The church's current vicar, the Rev. Richard Spray, showed me around. Like many medieval country churches, St. Wilfrid's had a makeover in the Victorian era, but the structure of the building Brewster knew remained largely intact. "The church is famous for what's not in it," Spray said. "Namely, the Brewsters and the other Pilgrims. But it's interesting to think that the Thanksgiving meal they had when they got to America apparently resembled a Nottinghamshire Harvest Supper—minus the turkey!"

A few hundred yards from St. Wilfrid's, I found the remains of Scrooby Manor, where William Brewster was born in 1566 or 1567. This esteemed Pilgrim father gets little recognition in his homeland—all that greets a visitor is a rusting "No Trespassing" sign and a jumble of half-derelict barns, quite the contrast to his presence in Washington, D.C. There, in the Capitol, Brewster is commemorated with a fresco that shows him—or, rather, an artist's impression of him—seated, with shoulder-length hair and a voluminous beard, his eyes raised piously toward two chubby cherubs sporting above his head.

Today, this rural part of eastern England in the county of Nottinghamshire is a world away from the commerce and bustle of London. But in William Brewster's day, it was rich in agriculture and maintained maritime links to northern Europe. Through the region ran the Great North Road from London to Scotland. The Brewster family was well respected here until William Brewster became embroiled in the biggest political controversy of their day, when Queen Elizabeth decided to have her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, executed in 1587. Mary, a Catholic whose first husband had been the King of France, was implicated in conspiracies against Elizabeth's continued Protestant rule.

Brewster's mentor, the secretary of state, became a scapegoat in the aftermath of Mary's beheading. Brewster himself survived the crisis, but he was driven from the glittering court in London, his dreams of worldly success dashed. His disillusionment with the politics of court and church may have led him in a radical direction—he fatefully joined the congregation of All Saints Church in Babworth, a few miles down the road from Scrooby.

There the small band of worshipers likely heard the minister, Richard Clyfton, extolling St. Paul's advice, from Second Corinthians, 6:17, to cast off the wicked ways of the world: "Therefore come out from them, and be separate from them, says the Lord, and touch nothing unclean." (This bit of scripture probably gave the Separatists their name.) Separatists wanted a better way, a more direct religious experience, with no intermediaries between them and God as revealed in the Bible. They disdained bishops and archbishops for their worldliness and corruption and wanted to replace them with a democratic structure led by lay and clerical elders and teachers of their own choosing. They opposed any vestige of Catholic ritual, from the sign of the cross to priests decked out in vestments. They even regarded the exchanging of wedding rings as a profane practice.

A young orphan, William Bradford, was also drawn into the Separatist orbit during the country's religious turmoil. Bradford, who in later life would become the second governor of Plymouth Colony, met William Brewster around 1602-3, when Brewster was about 37 and Bradford 12 or 13. The older man became the orphan's mentor, tutoring him in Latin, Greek and religion. Together they would travel the seven miles from Scrooby to Babworth to hear Richard Clyfton preach his seditious ideas—how everyone, not just priests, had a right to discuss and interpret the Bible; how parishioners should take an active part in services; how anyone could depart from the official Book of Common Prayer and speak directly to God.

In calmer times, these assaults on convention might have passed with little notice. But these were edgy days in England. James I (James VI as King of Scotland) had ascended to the throne in 1603. Two years later, decades of Catholic maneuvering and subversion had culminated in the Gunpowder Plot, when mercenary Guy Fawkes and a group of Catholic conspirators came very close to blowing up Parliament and with them the Protestant king.

Against this turmoil, the Separatists were eyed with suspicion and more. Anything smacking of subversion, whether Catholic or Protestant, provoked the ire of the state. "No bishop, no king!" thundered the newly crowned king, making it clear that any challenge to church hierarchy was also a challenge to the Crown and, by implication, the entire social order. "I shall make them conform," James proclaimed against the dissidents, "or I will hurry them out of the land or do worse."

He meant it. In 1604, the Church introduced 141 canons that enforced a sort of spiritual test aimed at flushing out nonconformists. Among other things, the canons declared that anyone rejecting the practices of the established church excommunicated themselves and that all clergymen had to accept and publicly acknowledge the royal supremacy and the authority of the Prayer Book. It also reaffirmed the use of church vestments and the sign of the cross in baptism. Ninety clergymen who refused to embrace the new canons were expelled from the Church of England. Among them was Richard Clyfton, of All Saints at Babworth.

Brewster and his fellow Separatists now knew how dangerous it had become to worship in public; from then on, they would hold only secret services in private houses, such as Brewster's residence, Scrooby Manor. His connections helped to prevent his immediate arrest. Brewster and other future Pilgrims would also meet quietly with a second congregation of Separatists on Sundays in Old Hall, a timbered black-and-white structure in Gainsborough. Here under hand-hewn rafters, they would listen to a Separatist preacher, John Smyth, who, like Richard Clyfton before him, argued that congregations should be allowed to pick and ordain their own clergy and worship should not be confined only to prescribed forms sanctioned by the Church of England.

"It was a very closed culture," says Sue Allan, author of Mayflower Maid, a novel about a local girl who follows the Pilgrims to America. Allan leads me upstairs to the tower roof, where the entire town lay spread at our feet. "Everyone had to go to the Church of England," she said. "It was noted if you didn't. So what they were doing here was completely illegal. They were holding their own services. They were discussing the Bible, a big no-no. But they had the courage to stand up and be counted."

By 1607, however, it had become clear that these clandestine congregations would have to leave the country if they wanted to survive. The Separatists began planning an escape to the Netherlands, a country that Brewster had known from his younger, more carefree days. For his beliefs, William Brewster was summoned to appear before his local ecclesiastical court at the end of that year for being "disobedient in matters of Religion." He was fined £20, the equivalent of $5,000 today. Brewster did not appear in court or pay the fine.

But immigrating to Amsterdam was not so easy: under a statute passed in the reign of Richard II, no one could leave England without a license, something Brewster, Bradford and many other Separatists knew they would never be granted. So they tried to slip out of the country unnoticed.

They had arranged for a ship to meet them at Scotia Creek, where its muddy brown waters spool toward the North Sea, but the captain betrayed them to the authorities, who clapped them in irons. They were taken back to Boston in small open boats. On the way, the local catchpole officers, as the police were known, "rifled and ransacked them, searching to their shirts for money, yea even the women further than became modesty," William Bradford recalled. According to Bradford, they were bundled into the town center where they were made into "a spectacle and wonder to the multitude which came flocking on all sides to behold them." By this time, they had been relieved of almost all their possessions: books, clothes and money.

After their arrest, the would-be escapees were brought before magistrates. Legend has it that they were held in the cells at Boston's Guildhall, a 14th-century building near the harbor. The cells are still here: claustrophobic, cage-like structures with heavy iron bars. American tourists, I am told, like to sit inside them and imagine their forebears imprisoned as martyrs. But historian Malcolm Dolby doubts the story. "The three cells in the Guildhall were too small—only six feet long and five feet wide. So you are not talking about anything other than one-person cells. If they were held under any sort of arrest, it must have been house arrest against a bond, or something of that nature," he explains. "There's a wonderful illustration of the constables of Boston pushing these people into the cells! But I don't think it happened."

Bradford, however, described that after "a month's imprisonment," most of the congregation were released on bail and allowed to return to their homes. Some families had nowhere to go. In anticipation of their flight to the Netherlands, they had given up their houses and sold their worldly goods and were now dependent on friends or neighbors for charity. Some rejoined village life.

If Brewster continued his rebellious ways, he faced prison, and possibly torture, as did his fellow Separatists. So in the spring of 1608, they organized a second attempt to flee the country, this time from Killingholme Creek, about 60 miles up the Lincolnshire coast from the site of the first, failed escape bid. The women and children traveled separately by boat from Scrooby down the River Trent to the upper estuary of the River Humber. Brewster and the rest of the male members of the congregation traveled overland.

They were to rendezvous at Killingholme Creek, where a Dutch ship, contracted out of Hull, would be waiting. Things went wrong again. Women and children arrived a day early. The sea had been rough, and when some of them got seasick, they took shelter in a nearby creek. As the tide went out, their boats were seized by the mud. By the time the Dutch ship arrived the next morning, the women and children were stranded high and dry, while the men, who had arrived on foot, walked anxiously up and down the shore waiting for them. The Dutch captain sent one of his boats ashore to collect some of the men, who made it safely back to the main vessel. The boat was dispatched to pick up another load of passengers when, William Bradford recalled, "a great company, both horse and foot, with bills and guns and other weapons," appeared on the shore, intent on arresting the would-be departees. In the confusion that followed, the Dutch captain weighed anchor and set sail with the first batch of Separatists. The trip from England to Amsterdam normally took a couple of days—but more bad luck was in store. The ship, caught in a hurricane-force storm, was blown almost to Norway. After 14 days, the emigrants finally landed in the Netherlands. Back at Killingholme Creek, most of the men who had been left behind had managed to escape. The women and children were arrested for questioning, but no constable wanted to throw them in prison. They had committed no crime beyond wanting to be with their husbands and fathers. Most had already given up their homes. The authorities, fearing a backlash of public opinion, quietly let the families go. Brewster and John Robinson, another leading member of the congregation, who would later become their minister, stayed behind to make sure the families were cared for until they could be reunited in Amsterdam.

Over the next few months, Brewster, Robinson and others escaped across the North Sea in small groups to avoid attracting notice. Settling in Amsterdam, they were befriended by another group of English Separatists called the Ancient Brethren. This 300-member Protestant congregation was led by Francis Johnson, a firebrand minister who had been a contemporary of Brewster's at Cambridge. He and other members of the Ancient Brethren had done time in London's torture cells.

Although Brewster and his congregation of some 100 began to worship with the Ancient Brethren, the pious newcomers were soon embroiled in theological disputes and left, Bradford said, before "flames of contention" engulfed them. After less than a year in Amsterdam, Brewster's discouraged flock picked up and moved again, this time to settle in the city of Leiden, near the magnificent church known as Pieterskerk (St. Peter's). This was during Holland's golden age, a period when painters like Rembrandt and Vermeer would celebrate the physical world in all its sensual beauty. Brewster, meanwhile, had by Bradford's account "suffered much hardship....But yet he ever bore his condition with much cheerfulness and contentation." Brewster's family settled in Stincksteeg, or Stink Alley, a narrow, back alley where slops were taken out. The congregation took whatever jobs they could find, according to William Bradford's later recollection of the period. He worked as a maker of fustian (corduroy). Brewster's 16-year-old son, Jonathan, became a ribbon maker. Others labored as brewer's assistants, tobacco-pipe makers, wool carders, watchmakers or cobblers. Brewster taught English. In Leiden, good-paying jobs were scarce, the language was difficult and the standard of living was low for the English immigrants. Housing was poor, infant mortality high.

After two years the group had pooled together money to buy a house spacious enough to accommodate their meetings and Robinson's family. Known as the Green Close, the house lay in the shadow of Pieterskerk. On a large lot behind the house, a dozen or so Separatist families occupied one-room cottages. On Sundays, the congregation gathered in a meeting room and worshiped together for two four-hour services, the men sitting on one side of the church, the women on the other. Attendance was compulsory, as were services in the Church of England.

Not far from the Pieterskerk, I find William Brewstersteeg, or William Brewster Alley, where the rebel reformer oversaw a printing company later generations would call the Pilgrim Press. Its main reason for being was to generate income, largely by printing religious treatises, but the Pilgrim Press also printed subversive pamphlets setting out Separatist beliefs. These were carried to England in the false bottoms of french wine barrels or, as the English ambassador to the Netherlands reported, "vented underhand in His Majesty's kingdoms." Assisting with the printing was Edward Winslow, described by a contemporary as a genius who went on to play a crucial role in Plymouth Colony. He was already an experienced printer in England when, at age 22, he joined Brewster to churn out inflammatory materials.

The Pilgrim Press attracted the wrath of authorities in 1618, when an unauthorized pamphlet called the Perth Assembly surfaced in England, attacking King James I and his bishops for interfering with the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. The monarch ordered his ambassador in Holland to bring Brewster to justice for his "atrocious and seditious libel," but Dutch authorities refused to arrest him. For the Separatists, it was time to move again—not only to avoid arrest. They were also worried about war brewing between Holland and Spain, which might bring them under Catholic rule if Spain prevailed. And they recoiled at permissive values in the Netherlands, which, Bradford would later recall, encouraged a "great licentiousness of youth in that country." The "manifold temptations of the place," he feared, were drawing youths of the congregation "into extravagant and dangerous courses, getting the reins off their necks and departing from their parents."

About this time, 1619, Brewster disappears briefly from the historical record. He was about 53. Some accounts suggest that he may have returned to England, of all places, there to live underground and to organize his last grand escape, on a ship called the Mayflower. There is speculation that he lived under an assumed name in the London district of Aldgate, by then a center for religious nonconformists. When the Mayflower finally set sail for the New World in 1620, Brewster was aboard, having escaped the notice of authorities.

But like their attempts to flee England in 1607 and 1608, the Leiden congregation's departure for America 12 years later was fraught with difficulties. In fact, it almost didn't happen. In July, the Pilgrims left Leiden, sailing from Holland in the Speedwell, a stubby overrigged vessel. They landed quietly in Southampton on the south coast of England. There they gathered supplies and proceeded to Plymouth before sailing for America in the 60-ton Speedwell and the 180-ton Mayflower, a converted wine-trade ship, chosen for its steadiness and cargo capacity. But after "they had not gone far," according to Bradford, the smaller Speedwell, though recently refitted for the long ocean voyage, sprang several leaks and limped into port at Dartmouth, England, accompanied by the Mayflower. More repairs were made, and both set out again toward the end of August. Three hundred miles at sea, the Speedwell began leaking again. Both ships put into Plymouth—where some 20 of the 120 would-be Colonists, discouraged by this star-crossed prologue to their adventure, returned to Leiden or decided to go to London. A handful transferred to the Mayflower, which finally hoisted sail for America with about half of its 102 passengers from the Leiden church on September 6.

On their arduous, two-month voyage, the 90-foot ship was battered by storms. One man, swept overboard, held onto a halyard until he was rescued. Another succumbed to "a grievous disease, of which he died in a desperate manner," according to William Bradford. Finally, though, on November 9, 1620, the Mayflower sighted the scrubby heights of what is known today as Cape Cod. After traveling along the coast that their maps identified as New England for two days, they dropped anchor at the site of today's Provincetown Harbor of Massachusetts. Anchored offshore there on November 11, a group of 41 passengers—only the men—signed a document they called the Mayflower Compact, which formed a colony composed of a "Civil Body Politic" with just and equal laws for the good of the community. This agreement of consent between citizens and leaders became the basis for Plymouth Colony's government. John Quincy Adams viewed the agreement as the genesis of democracy in America.

Among the passengers who would step ashore to found the colony at Plymouth were some of America's first heroes—such as the trio immortalized by Longfellow in "The Courtship of Miles Standish": John Alden, Priscilla Mullins and Standish, a 36-year-old soldier—as well as the colony's first European villain, John Billington, who was hanged for murder in New England in 1630. Two happy dogs, a mastiff bitch and a spaniel belonging to John Goodman, also bounded ashore.

It was the beginning of another uncertain chapter of the Pilgrim story. With winter upon them, they had to build homes and find sources of food, while negotiating the shifting political alliances of Native American neighbors. With them, the Pilgrims celebrated a harvest festival in 1621—what we often call the first Thanksgiving.

Perhaps the Pilgrims survived the long journey from England to Holland to America because of their doggedness and their conviction that they had been chosen by God. By the time William Brewster died in 1644, at age 77, at his 111-acre farm at the Nook, in Duxbury, the Bible-driven society he had helped create at Plymouth Colony could be tough on members of the community who misbehaved. The whip was used to discourage premarital sex and adultery. Other sexual offenses could be punished by hanging or banishment. But these early Americans brought with them many good qualities too—honesty, integrity, industry, rectitude, loyalty, generosity, flinty self-reliance and a distrust of flashiness—attributes that survive down through the generations.

Many of the Mayflower descendants would be forgotten by history, but more than a few would rise to prominence in American culture and politics—among them Ulysses S. Grant, James A. Garfield, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Orson Welles, Marilyn Monroe, Hugh Hefner and George W. Bush.

Simon Worrall, who lives in Herefordshire, England, wrote about cricket in the October issue of Smithsonian.