Rain Forest Rebel

In the Amazon, researchers documenting the ways of native peoples join forces with a chief to stop illegal developers from destroying the wilderness

Inside a thatched-roof schoolhouse in Nabekodabadaquiba, a village deep in Brazil's Amazon rain forest, Surui Indians and former military cartographers huddle over the newest weapons in the tribe's fight for survival: laptop computers, satellite maps and hand-held global positioning systems. At one table, Surui illustrators place a sheet of tracing paper over a satellite image of the Sete de Setembro indigenous reserve, the enclave where this workshop is taking place. Painstakingly, the team maps out the sites of bow-and-arrow skirmishes with their tribal enemies, as well as a bloody 1960s attack on Brazilian telegraph workers who were laying cable through their territory. "We Suruis are a warrior tribe," one of the researchers says proudly.

A few feet away, anthropologists sketch out groves of useful trees and plants on another map. A third team charts the breeding areas of the territory's wildlife, from toucans to capybaras, the world's largest rodent. When the task is finished, in about a month, the images will be digitized and overlaid to create a map documenting the reserve in all its historical, cultural and natural richness. "I was born in the middle of the forest, and I know every corner of it," says Ibjaraga Ipobem Surui, 58, one of the tribal elders whose memories have been tapped. "It's very beautiful work."

The project, intended to document an indigenous culture, appears harmless enough. But this is a violent region, where even innocuous attempts to organize the Indians can provoke brutal responses from vested interests. In the past five years, 11 area tribal chiefs, including 2 members of the Surui tribe and 9 from the neighboring Cinta Largas, have been gunned down—on the orders, say tribe members, of loggers and miners who have plundered Indian reserves and who regard any attempt to unite as a threat to their livelihoods. Some of these murdered chiefs had orchestrated protests and acts of resistance, blocking logging roads and chasing gold miners from pits and riverbeds—actions that disrupted operations and caused millions of dollars in lost revenue. In August, the Surui chief who, along with tribal elders, brought the map project to the reserve, 32-year-old Almir Surui, received an anonymous telephone call warning him, he says, to back off. "You are potentially hurting many people," he says he was told. "You'd better be careful." Days later, two Surui youths alleged at a tribal meeting that they had been offered $100,000 by a group of loggers to kill Almir Surui.

For the past 15 years, Almir—a political activist, environmentalist and the first member of his tribe to attend a university—has been fighting to save his people and the rain forest they inhabit in the western state of Rondônia. His campaign, which has gained the support of powerful allies in Brazil and abroad, has inspired comparisons to the crusade of Chico Mendes, the Brazilian rubber tapper who led a highly publicized movement against loggers and cattle ranchers in neighboring Acre state in the 1980s. "If it weren't for people like Almir, the Surui would have been destroyed by now," says Neri Ferigobo, a Rondônia state legislator and an important political ally. "He's brought his people back from near extinction; he's made them understand the value of their culture and their land."

Almir's campaign has reached its fullest expression in the mapmaking project. Besides documenting the tribe's history and traditions and detailing its landscape, in an endeavor known as ethnomapping, his scheme could have significant economic effect. As part of the deal for bringing ethnomapping to his people—an ambitious project that will provide training, jobs and other benefits to the near-destitute Surui—Almir persuaded 14 of the 18 Surui chiefs to declare a moratorium on logging in their parts of the reserve. Although the removal of timber from the indigenous areas is illegal, an estimated 250 logging trucks go in and out of the reserve monthly, according to tribal leaders, providing timber to 200 sawmills, employing some 4,000 people, scattered throughout the region. After Almir persuaded the chiefs to unite in a logging ban, many of them threw chains over logging roads, and the amount of timber leaving the rain forest has decreased. That's when the first death threat came in. In mid-August, Almir flew for his own protection to Brasília, where federal police promised to launch an investigation and provide him with bodyguards; neither, he says, was forthcoming. Days later, an American environmental group, the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), evacuated him to Washington, D.C., where he remained until late September. After returning home, he says, someone tried to run him off the road as he traveled back to the reserve. "I have no doubt they were trying to kill me," he says.

When I asked him if he saw parallels between himself and Chico Mendes, who was shot dead by a contract killer at his home in December 1988, he waved his hand dismissively. "I've got no desire to become a dead hero," he replied. Asked what precautions he was taking, however, he shrugged and, with a touch of bravado, answered: "I rely on the spirits of the forest to protect me."

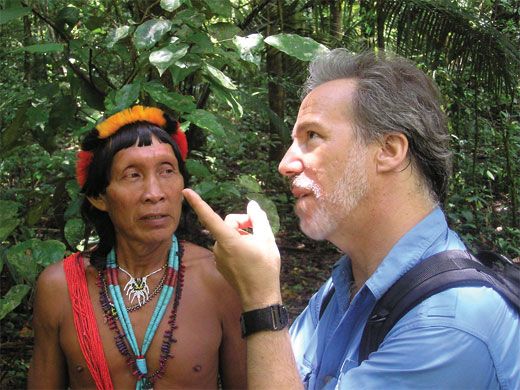

I first met Almir on a humid morning in mid-October, after flying three hours north from Brasília to Porto Velho (pop. 305,000), Rondônia's steamy capital and the gateway to the Amazon. The chief had been back in Brazil only a couple of weeks following his hasty evacuation to Washington. He had invited me to travel with him to the Sete de Setembro Reserve, the 600,000-acre enclave set aside for the Surui by the Brazilian government in 1983. The reserve is named after the day, September 7, 1968, that the Surui had their first face-to-face contact with white men: the meeting took place after Brazilian officials from the Indian affairs department had placed trinkets—machetes, pocketknives, axes—in forest clearings as a gesture of friendship, gradually winning the Indians' trust. (By coincidence, the 7th of September is also the date, in 1822, that Brazil declared its independence from Portugal.)

Almir was waiting at the arrival gate. He is a short, stocky man with a bulldog head, a broad nose and jet-black hair cut in traditional bangs in front and worn long in back. He greeted me in Portuguese (he speaks no English) and led the way to his Chevrolet pickup truck parked out front. Almir was joined by Vasco van Roosmalen, Brazil program director for the Amazon Conservation Team, which is funding the ethnomapping project. A tall, amiable, 31-year-old Dutchman, van Roosmalen grew up in the Brazilian Amazon, where his father, a noted primatologist, discovered several new species of monkey. Also on the trip was Uruguayan Marcelo Segalerba, the team's environmental coordinator. After a lunch of dorado stew, manioc and rice at a local café, we set out on the Rondônia Highway, the BR-364, on the 210-mile drive southeast to the reserve, past cattle ranches, farms and hardscrabble towns that looked as if they'd been thrown up overnight. As we approached the ramshackle roadside settlement of Ariquemes, Almir told us, "This land belonged to the Ariquemes tribe, but they were wiped out by the white men. Now the only trace of them is the name of this town."

Less than two generations ago, the Surui were among several large groups of Indians who roamed an area of primary rain forest along the borders of what are now Rondônia and Mato Grosso states. They wore loincloths, lived off the animals they hunted with bows and arrows and trapped in the forest, and battled for territory with other tribes in the area. (Known in their own language as the Paiterey, or "Real People," the Surui acquired their now more commonly used name in the 1960s. That was when Brazilian government officials asked the rival Zora tribe to identify a more elusive group the officials had also seen in the forest. The Zora answered with a word that sounded like "surui," meaning "enemy.") Then, in the early 1980s, Brazil embarked on the most ambitious public-works project in the country's history: a two-lane asphalt road that today runs east-west for at least 2,o00 miles from the state of Acre, through Rondônia and into the neighboring state of Mato Grosso. Financed by the World Bank and the Brazilian government, the multi-billion-dollar project attracted hundreds of thousands of poor farmers and laborers from Brazil's densely populated south in search of cheap, fertile land. A century and a half after the American West was settled by families in wagon trains, Brazil's conquest of its wilderness unfolded as newcomers penetrated deeper into the Amazon, burning and clear-cutting the forest. They also clashed frequently, and often violently, with indigenous tribes armed only with bows and arrows.

What followed was a pattern familiar to students of the American West: a painful tale of alcoholism, destruction of the environment and the disappearance of a unique culture. Catholic and evangelical missionaries stripped the Indians of their myths and their traditions; exposure to disease, especially respiratory infections, killed off thousands. Some tribes simply vanished. The Surui population dropped from about 2,000 before "contact" to a few hundred by the late 1980s. The psychological devastation was nearly as severe. "When you have this white expansion, the Indians start seeing themselves as the white man sees them—as savages, as obstacles to development," explains Samuel Vieira Cruz, an anthropologist and a founder of Kanindé, an Indian rights group based in Porto Velho. "The structure of their universe gets obliterated."

In 1988, faced with a population on the verge of dying out, Brazil ratified a new constitution that recognized the Indians' right to reclaim their original lands and preserve their way of life. Over the next decade, government land surveyors demarcated 580 Indian reserves, 65 percent of them in the Amazon. Today, according to FUNAI, the federal department established in 1969 to oversee Indian affairs, Indian tribes control 12.5 percent of the national territory, though they number just 450,000, or .25 percent of Brazil's total population. These reserves have become islands of natural splendor and biodiversity in a ravaged landscape: recent satellite imagery of the Amazon shows a few islands of green, marking the Indian enclaves, surrounded by vast splotches of orange, where agriculture, ranching and logging have eradicated the woodlands.

The Brazilian government has been largely supportive of the Amazon mapmaking projects. In 2001 and 2002, the Amazon Conservation Team collaborated on two ambitious ethnomapping schemes with FUNAI and remote indigenous tribes in the Xingu and Tumucumaque reserves. In 2003, the Brazilian ambassador to the United States, Roberto Abdenur, presented the new maps at a press conference in Washington. According to van Roosmalen, ACT maintains "good relationships" with nearly all agencies of the Brazilian government that deal with Indian affairs.

But the future of the reserves is in doubt. Land disputes between Indians and developers are growing, as increasing assassinations of tribal leaders attest. A 2005 report by Amnesty International declared that the "very existence of Indians in Brazil" is being threatened. Pro-development politicans, including Ivo Cassol, the governor of Rondônia, who was returned to office with 60 percent of the vote this past September, call for the exploiting of resources on Indian reserves. Cassol's spokesman, Sergio Pires, told me matter-of-factly that "the history of colonization has been the history of exterminating Indians. Right now you have small groups left, and eventually they will all disappear."

Throughout Brazil, however, advocates of rain forest preservation are countering pro-development forces. President Lula da Silva recently announced a government plan to create a coherent rain forest policy, auctioning off timber rights in a legally sanctioned area. JorgeViana, former governor of the state of Acre, told the New York Times, "This is one of the most important initiatives that Brazil has ever adopted in the Amazon, precisely because you are bringing the forest under state control, not privatizing it." Another state governor, Eduardo Braga of Amazonas, created the Zona Franca Verde (Green Free Trade Zone), which lowered taxes on sustainable rain forest products, from nuts to medicinal plants, in order to increase their profitability. Braga has set aside 24 million acres of rain forest since 2003.

The stakes are high. If indigenous peoples disappear, environmentalists say, the Amazon rain forest will likely vanish as well. Experts say as much as 20 percent of the forest, sprawling over 1.6 million square miles and covering more than half of Brazil, has already been destroyed. According to Brazil's Environmental Ministry, deforestation in the Amazon in 2004 reached its second-highest rate ever, with ranchers, soybean farmers and loggers burning and cutting down 10,088 square miles of rain forest, an area roughly the size of Vermont. "The fate of indigenous cultures and that of the rain forest are intricately intertwined," says Mark Plotkin, founding director of ACT, which is providing financial and logistical support to the Surui's mapping project and several others in the rain forest. So far the organization has ethnomapped 40 million acres in Brazil, Suriname and Columbia. By 2012, it hopes to have put together maps covering 138 million acres of Indian reserves, much of it contiguous. "Without the rain forest, these traditional cultures cannot survive," Plotkin says. "At the same time, indigenous peoples have repeatedly been shown to be the most effective guardians of the rain forests they inhabit."

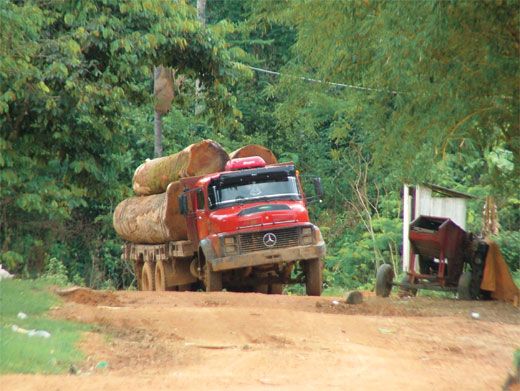

After two days driving into the Amazon with Almir, we turned off from the Rondônia Highway and bounced down a dirt road for half an hour. Farmers with blond hair and Germanic features stared impassively from the roadside—part of a wave of migrants who came up to the Amazon from the more densely populated southern Brazilian states in the 1970s and '80s. Just before a sign that marks the entrance to the Sete de Setembro Reserve, Almir pulled up next to a small lumber mill. It was one of dozens, he said, that have sprung up on the edge of the reserve to process mahogany and other valuable hardwoods plundered from the forest, often with the complicity of tribal chiefs. Two flatbed trucks, piled with 40-foot logs, were parked in front of a low, wood-plank building. The sawmill operator, accompanied by his adolescent son, sat on a bench and stared, unsmiling, at Almir. "I've complained about them many times, but they're still here," Almir told me.

Moments later, we found ourselves in the jungle. The screams of spider and howler monkeys and the squawks of red macaws echoed from dense stands of bamboo, wild papaya, mahogany, bananas and a dozen varieties of palm. It had rained the night before, and the truck churned in a sea of red mud, grinding with difficulty up a steep hill.

We arrived at a small Surui village, where a mapmaking seminar was taking place. Tribal elders had been invited here to share their knowledge with researchers on the project. They congregated on benches around rough tables beneath a palm-frond canopy, alongside a creek that, I was told, was infested with piranhas. The elders were striking men in their 50s and 60s, a few even older, with bronze skin, black hair cut in bangs and faces adorned with tribal tattoos—thin blue lines that ran horizontally and vertically along their cheekbones. The oldest introduced himself as Almir's father, Marimo Surui. A former tribal chief, Marimo, 85, is a legend among the Indians; in the early 1980s, he single-handedly seized a logging truck and forced the driver to flee. Dozens of policemen surrounded the truck in response, and Marimo confronted them alone, armed only with a bow and arrow. "They had machine guns and revolvers, but when they saw me with my bow and arrow, they shouted, 'Amigo! Amigo! Don't shoot,' and tried to hide behind a wall," he told me. "I followed them and said, 'You cannot take this truck.'" The police, apparently bewildered by the sight of an angry Indian in war paint with a bow and arrow, retreated without firing a shot.

The incident will undoubtedly be included in the Surui map. In the first phase of the process, Indians trained as cartographic researchers traveled to villages across the reserve and interviewed shamans (the Surui have only three left, all in their 80s), tribal elders and a broad spectrum of tribe members. They identified significant locations to be mapped—ancestral cemeteries, ancient hunting grounds, battle sites and other areas of cultural, natural and historical importance. In phase two, the researchers journeyed on foot or by canoe through the reserve with GPS systems to verify the places described. (In previous mapmaking exercises, the elders' memories of locations have proved nearly infallible.) The initial phase has brought younger Indians in touch with a lost history. Almir hopes that by infusing the Surui with pride in their world, he can unite them in resistance to those who want to eradicate it.

Almir Surui is one of the youngest Surui members with a clear memory of the early Indian-white battles. In 1982, when he was 7, the Surui rose up to drive settlers out of the forest. "The Surui came to this settlement with bows and arrows, grabbed the white invaders, hit them with bamboo sticks, stripped them and sent them out in their underwear," Almir tells me, as we sit on plastic chairs on the porch of his blue-painted concrete-block house in Lapetania on the southwest edge of the reserve. The hamlet is named after a white settler who built a homestead here in the 1970s. The cleared land was taken back by the Indians in the wake of the revolt; they built their own village on top of it. Shortly thereafter, the police foiled a planned massacre of the Surui by whites; FUNAI stepped in and marked out the borders of the Sete de Setembro Reserve.

The demarcation of their territory, however, could not keep out the modern world. And though the Surui were forced to integrate into white society, they derived few benefits from it. A shortage of schools, poor medical care, alcoholism and steady depletion of the forest thinned their ranks and deepened their poverty. This problem only increased in the late 1980s, when the Surui divided into four clans and dispersed to different corners of the reserve, a strategic move intended to help them better monitor illicit logging. Instead, it turned them into factions.

At age 14, while attending secondary school in Cacoal, Almir Surui began showing up at tribal meetings at the reserve. Three years later, in 1992, at 17, he was elected chief of the Gamep, one of the four Surui clans, and began looking for ways to bring economic benefits to his people while preserving their land. He came to the attention of an indigenous leader in Brazil's Minas Gerais state, Ailton Krenak, who helped him obtain a scholarship to the University of Goiânia, near Brasília. "Education can be a double-edged sword for the Indians, because it brings them into contact with white men's values," says Samuel Vieira Cruz. "Almir was an exception. He spent three years in college, but he kept his ties to his people."

Almir got his first big opportunity to demonstrate his political skills a couple of years later. In the mid-1990s, the World Bank launched a $700 million agricultural project, Plana Fora, designed to bring corn-threshing equipment, seeds, fertilizers and other aid to the reserves. Almir and other tribal leaders soon realized, however, that the Indians were receiving almost none of the promised money and material. In 1996, he confronted the World Bank representative and demanded that the lender bypass FUNAI, the intermediary, and give the money directly to the tribes. In Porto Velho, Almir organized a protest that drew 4,000 Indians from many different tribes. Then, in 1998, the young chief was invited to attend a meeting of the World Bank board of directors in Washington, D.C. where a restructuring of the project would be discussed.

Twenty-three years old, speaking no English, Almir and another Brazilian rain forest activist, Jose Maria dos Santos, who had joined him on the trip, checked into a Washington hotel and ventured out to find something to eat. They walked into the first restaurant they happened upon and pointed at random to items on the menu. The waitress laid a plate of sushi in front of Almir and a chocolate cake before his colleague. "We skimmed the chocolate fudge off the cake and didn't eat anything else," he says. For the next week, he says, the two ate all their meals at a chicken rotisserie near their hotel. He convinced the World Bank to audit its loan to Rondônia.

Back home, Almir began reaching out to the press, religious leaders and sympathetic politicians to publicize and support his cause. Powerful government figures came to see him as a threat. "The governor pleaded with me to stop the [World Bank] campaign, and he offered me 1 percent of the $700 million project to do so. I refused," Almir tells me. "Later, in Porto Velho, [the governor's staffers] put a pile of cash in front of me, and I said, 'Give me the telephone and I'll call O Globo [one of Brazil's largest newspapers] to photograph the scene.' They said, 'If you tell anybody about this you will disappear.'" In the end, the World Bank plan was restructured, and the Indians did get paid directly.

Other accomplishments followed. Almir successfully sued the state of Rondônia to force officials to build schools, wells and medical clinics within the reserve. He also focused on bringing the Surui back from near extinction, advising families to have more children and encouraging people from other tribes to settle on Surui land; the population has risen from several hundred in the late 1980s to about 1,100 today, half of what it was before contact. "Without Almir, his work and leaders like him, the Surui would probably have joined tribes like the Ariquemes and disappeared into the vacuum of Rondônia history," van Roosmalen told me. "One has to remember what stakes these people are facing. It is not one of poverty versus riches, but survival in the face of annihilation."

Soon after we arrive in the Surui villages to observe the mapmaking project, Almir leads me through a hodgepodge of thatched and tin-roofed structures surrounding an unkempt square of grass and asphalt. A dozen women, surrounded by naked children, sit on the concrete patio of a large house making necklaces out of armadillo spines and palm seed shells. A broken Honda motorbike rusts in the grass; a capuchin monkey sits tethered by a rope. A bristly wild pig, somebody's pet, lies panting in the noonday heat. The village has a shabby, somnolent air. Despite Almir's efforts, economic opportunities remain minimal—handicraft selling and cultivation of manioc, bananas, rice and beans. A few Surui are teachers at the reserve's primary school; some of the elders collect government pensions. "It's a poor place," Almir says. "The temptation to surrender to the loggers are great."

With the encouragement of Almir and a handful of like-minded chiefs, the Surui have begun exploring economic alternatives to logging. Almir leads van Roosmalen and me on a trail that wanders past his village; we are quickly swallowed up by the rain forest. Almir points out mahogany saplings that he has planted to replace trees cut down illegally. The Surui have also revived a field of shade-grown coffee started decades ago by white settlers. His "50-year plan" for Surui development, which he and other village chiefs drafted in 1999, calls also for extraction of therapeutic oils from the copaiba tree, the cultivation of Brazil nuts and acai fruits and the manufacture of handicrafts and furniture. There is even talk about a "certified logging" program that would allow some trees to be cut and sold under strict controls. Profits would be distributed among tribe members, and for every tree cut, a sapling would be planted.

After half an hour, we arrive at an Indian roundhouse, or lab-moy, a 20-foot-high, dome-like structure built of thatch, supported by bamboo poles. Almir and two dozen other Surui built the structure in 15 days last summer. They intend to use it as an indigenous research and training center. "The struggle is to guarantee [the Surui] alternative incomes: the process has now begun," Almir says.

He has no illusions about the difficulty of his task, realizing that the economic alternatives he has introduced take time and that the easy money proffered by loggers is hard to resist. "The chiefs know it's wrong, but they're attracted to the cash," van Roosmalen says. "The leaders get up to $1,000 a month. It's the most divisive issue that the Surui have to deal with." Henrique Yabadai Surui, a clan chief and one of Almir's allies in the fight, had told me that the unity of 14 chiefs opposed to logging has begun to fray. "We've started receiving threats, and there's no security. Messages have been sent: 'Stop getting in the way.' It is very difficult. We all have children that we need to take care of."

We stop unannounced at an Indian village at the eastern edge of the reserve. A logging truck, with five huge hardwoods stacked in back, is parked on the road. We walk past barking dogs, chickens and the charred remains of a roundhouse that burned down the week before in a fire that was started, we are told, by a 6-year-old boy who had been playing with matches. Joaquim Surui, the village chief, is taking a nap in a hammock in front of his house. Wearing a T-shirt bearing the English words LIVE LIFE INTENSELY, he jumps to his feet. When we inquire about the truck, he fidgets. "We're not permitting logging anymore," he says. "We're going to try out economic alternatives. That lumber truck was the last one we allowed. It's broken down, and the driver went off to get spare parts." Later, I ask Almir if he believes Joaquim's story. "He's lying," he says. "He's still in business with the loggers."

Almir Surui doesn't expect much official help. Although FUNAI, the Indian affairs agency, is charged with protecting natural resources within the reserves, several former FUNAI officials are said to have ties to the timber and mining industries, and the agency, according to indigenous leaders and even some FUNAI administrators, has been ineffectual in stopping the illegal trade.

Neri Ferigobo, the Rondônia legislator and ally of the Surui, says FUNAI remains vulnerable to pressure from top politicians in the Amazon. "All Rondônia's governors have been development-oriented," he charges. "The people who founded Rondônia had a get-rich-quick mentality, and that has carried down to today."

As for Almir Surui, he is on the road constantly these days, his work funded by the Brazilian government and various international organizations, particularly the Amazon Conservation Team. He commutes by small planes between Brasília, Porto Velho and other Brazilian cities, attending a stream of donor meetings and indigenous affairs conferences. He says he gets barely four days a month at home, not enough to keep in close touch with his community. "I'd like to spend more time here, but I've got too many responsibilities."

I asked Neri Ferigobo, Almir's ally in the Rondônia state legislature, if Almir's increasing activism made his assassination likely. "People know that if Almir is killed, he'll be another Chico Mendes, but that doesn't give him total protection," Ferigobo told me. "Still, I think Almir will survive. I don't think they'd be that rash to kill him."

About 4 p.m. of the third day, the mapmaking seminar draws to a close. The Indians are preparing to celebrate with an evening of dancing, singing and displays of bow-and-arrow prowess. With the encouragement of Almir and other Indian leaders, the tribe has revived its traditional dances and other rituals. Outside the schoolhouse, a dozen elders have adorned themselves in feathered headdresses and belts of armadillo hide; now they daub themselves with black war paint made from the fruit of the jenipapo tree. (The elders insist on decorating me as well, and I reluctantly agree; it will take more than three weeks for the paint to fade.) Marimo Surui, Almir's father, brandishes a handmade bow and a fistful of arrows; each has been fashioned from two harpy-eagle feathers and a slender bamboo shaft that narrows to a deadly point. I ask how he feels about the work his son is doing, and about the threats he has received. He answers in his native Indian language, which is translated first into Portuguese, then English. "It's bad for a father to have a son threatened," he says, "but everyone of us has passed through dangerous times. It is good that he's fighting for the future."

Almir lays a hand on his father's shoulder. He has painted the lower part of his face the color of charcoal, and even dressed in Western clothing—jeans, polo shirt, Nikes—he cuts a fierce figure. I ask him how white Brazilians react to him when he is so adorned. "It makes them nervous," he tells me. "They think it means that the Indians are getting ready for another war." In a way, that war has already begun, and Almir, like his father 25 years before him, stands virtually unprotected against his enemies.

Freelancer Joshua Hammer is based in Berlin. Photographer Claudio Edinger works out of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)