Saving Machu Picchu

Will the opening of a bridge give new life to the surrounding community or further encroach upon the World Heritage Site?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/machu-wide.jpg)

When Hiram Bingham, a young Yale professor, discovered Machu Picchu in 1911, he found a site overrun with vegetation. At an altitude of nearly 8,000 feet, the ruins, which sat above the cloud line in Peru's Andes Mountains, had remained relatively undisturbed for more than 300 years. Media in the United States declared it one of South America's most important and well-preserved sites.

Now nearly 2,500 tourists visit Machu Picchu everyday. This influx of visitors has caused a dilemma: How can Peru promote the ruins as a tourist destination, while also preserving the fragile ancient city? In March, a controversial bridge opened within the Machu Picchu buffer zone, some four kilometers outside of the sanctuary, making available yet another pathway to visitors. This development has caused heightened alarm among those who find it increasingly difficult to protect the World Heritage Site.

Bingham probably never envisioned the sheer number of people visiting Machu Picchu today. After all, he came upon the site by chance. While exploring Peru on a scientific expedition, Bingham met a local tavern-keeper Melchior Arteaga who described ruins at the top of a high mountain. In July 1911, a farmer in the area led Bingham up a treacherous incline through thickly matted jungle to an ancient city.

Buried under hundreds of years of brush and grass, the settlement was a collection of beautiful stone buildings and terraced land—evidence of advanced agricultural knowledge. This site, Bingham believed, was the birthplace of the Inca society, one of the world's largest Native American civilizations.

At its height, the empire that natives called Tahuantinsuyu spanned some 2,500 miles across what is now Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Bolivia and parts of Argentina. It was a society of great warriors with both architectural and agricultural know-how, whose 300-year reign came to an end in the 1500s when Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his army invaded the area.

Machu Picchu, Bingham came to believe, was not only the birthplace of the Inca, but the last surviving city of the empire as well. He also thought that the area held a great religious significance. With evidence of a high number of female remains, Bingham postulated that the city was home to a cult of women, deemed the Virgins of the Sun, who found safe haven here, away from the Spanish conquistadors.

Bingham took several hundred pictures of Machu Picchu and published his findings in National Geographic. The explorer also shipped several thousand artifacts back to Yale for further investigation. That the university still has many of these on display has become a point of contention in recent years between Yale and the Peruvian government.

After years of analysis, scholars have put forth an explanation of Machu Picchu that differs from Bingham's interpretation. Archaeological evidence points to a more balanced ratio of female and male remains at the site, dismissing the Virgins of the Sun story. Instead, they believe the early Incan ruler Pachacútec set up Machu Picchu as one of his royal retreats. In the mid 1400s, the Inca constructed the city with intensive planning that complemented its natural settings. A couple thousand people lived there in its heyday, but they quickly evacuated the city during the Spanish invasion. Save for a couple of farmers, the city was left abandoned for hundreds of years.

Peru recognized the cultural tourist attraction it had in Machu Picchu right away after Bingham re-discovered it, but many years passed before backpackers arrived on holiday. In the 1950s and 60s, tourists could visit the site and, after being admitted by a lone guard, take a nearly private tour of the area. In 1983, UNESCO named Machu Picchu a World Heritage Site for its cultural significance in the area. In the 1990s, as Peru's guerrilla war ended, more and more visitors flocked to the area. Now some 300,000 people visit every year, arriving by foot, train, even helicopter.

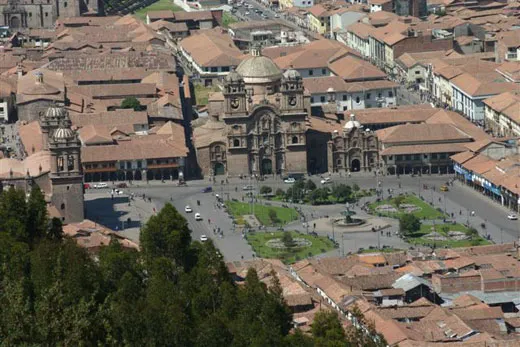

Tourism at Machu Picchu now boosts Peru's economy to more than $40 million a year. Aguas Calientes, a town constructed at the base of mountain, has become a tourist mecca with more than a hundred hotels, souvenir shops and restaurants. Perurail, a railway owned by Cuzco to the base of the mountain, where a bus takes tourists to the top.

Predictably, the tourist boom has impacted the area. The thousands of people hiking through the ancient Inca city have worn down its fragile pathways. In 2000, during the shooting of a beer commercial, a crane damaged a sacred stone pillar on the site. Afraid that the site would become overrun, UNESCO issued the Peruvian government a warning and threatened to put Machu Picchu on the endangered sites list. This means that the government has not maintained the site to UNESCO standards. "It's the first step in removing the site from the World Heritage list," says Roberto Chavez, the task team leader for the Vilcanota Valley Rehabilitation and Management Project, a World Bank initiative devised to protect Peru's Sacred Valley and promote sustainable tourism in the area. In response, the Peruvian Institute of Culture limited the number of visitors to 2,500 a day, although this number is still under review.

"A group of experts is studying how many visitors the site can exactly support without causing damage to the structure," says Jorge Zegarra Balcazar, director of the Institute of Culture. "Right now, the experts feel that more than 2,500 could contribute to the deterioration of the site."

A few miles from Machu Picchu sits Santa Teresa. Isolated by the surrounding mountains, the town has not benefited from tourism as much as Cuzco and Aguas Calientas. The community, instead, relies on its produce to bring in money. In the past, locals loaded their wares in Santa Teresa on a train that traveled to Cuzco. In 1998, a flood washed away the bridge that connected the train to the town. The government refused to rebuild it because of its close proximity to Machu Picchu. This forced some locals to travel to Cuzco on a badly worn road around mountains, in all, nearly a 15-hour trip. Others crossed the Vilcanota River using a makeshift bridge made of a metal cable and pulley system, where they pulled themselves across while sitting in what amounts to a human-sized bucket. From there, they took their goods to a train stationed at a hydroelectric power plant located within the sanctuary of Machu Picchu.

In 2006, Felia Castro, then mayor of the province, authorized the construction of a new bridge. She felt it would bring tourism to the area and also break the monopoly of Perurail, one of the only motorized routes to the foot of Machu Picchu's hill. The railway, which has operated since 1999, charges anywhere between $41 and $476, depending on how luxurious the ride, for roundtrip tickets from Cuzco to Machu Picchu.

More importantly, the bridge, which Castro planned to open to automobile traffic, reduces the drive to Cuzco significantly, and it also provides a quicker connection to the train at the hydroelectric plant. The bridge was so important to Castro that she ignored warnings and orders from the government and other organizations, who feared the new outlet for tourists, automobiles, and trucks would further harm the health of Machu Picchu. She even told press she would was willing to go to jail for its construction.

"We are dead set against it," says Chavez, who adds that automobile traffic has threatened other World Heritage Sites in the area. His group sought an injunction against the bridge, stalling construction for some time. Now that it has opened, the World Bank project staff hopes to restrict automobile traffic on the bridge, and they are working on alternatives such as pedestrian bridges for the locals in the area.

Balcazar at Peru's Institute of Culture endorses the bridge, but not its location, which sits inside the buffer zone of Machu Picchu. "Originally the bridge was for pedestrians only," says Balcazar. "Mayor Felia Castro opened the bridge to vehicle use. We are concerned about the conservation of Machu Picchu."

Others find the construction of the bridge a little less black and white. "This is a very complicated issue," says Norma Barbacci, Director of Field Projects at the World Monument Fund in New York. She understands that there is a local need, but still remains concerned for the health of Machu Picchu. "Every time you open a road or a railway, it's not just the bridge, it's all of the potential development."

Now that the bridge is complete—it opened March 24th to no protests—,the different organizations involved have resolved to work together. "All the different parties have joined forces with the Institute of Culture and World Heritage to bring a compromise to restrict the use of public transportation and private vehicles on the bridge," says Balcazar.

UNESCO is sending a team in late April and May to evaluate what impact, if any, the bridge has had on Machu Picchu. Chavez anticipates that UNESCO may once again threaten to put Machu Picchu on the endangered sites list. If this happens, he says, "it would be a black eye for the government, especially a government that relies on tourism."

Whitney Dangerfield is a regular contributor to Smithsonian.com.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.