Searching for Buddha in Afghanistan

An archaeologist insists a third giant statue lies near the cliffs where the Bamiyan Buddhas, destroyed in 2001, once stood

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bamiyan-cliff-face-cavity-Buddha-631.jpg)

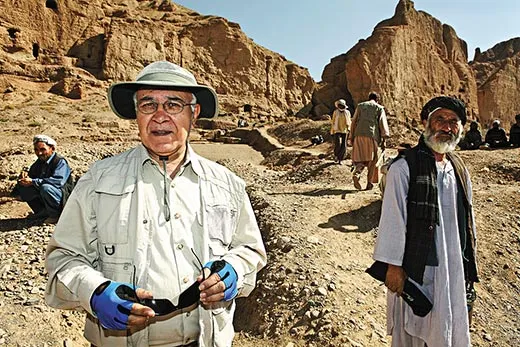

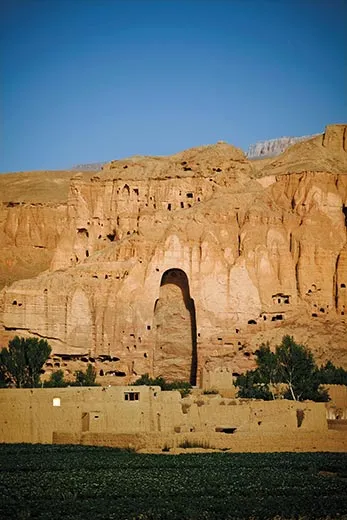

Clad in a safari suit, sun hat, hiking boots and leather gloves, Zemaryalai Tarzi leads the way from his tent to a rectangular pit in the Bamiyan Valley of northern Afghanistan. Crenulated sandstone cliffs, honeycombed with man-made grottoes, loom above us. Two giant cavities about a half-mile apart in the rock face mark the sites where two huge sixth-century statues of the Buddha, destroyed a decade ago by the Taliban, stood for 1,500 years. At the base of the cliff lies the inner sanctum of a site Tarzi calls the Royal Monastery, an elaborate complex erected during the third century that contains corridors, esplanades and chambers where sacred objects were stored.

"We're looking at what used to be a chapel covered with murals," the 71-year-old archaeologist, peering into the pit, tells me. Rulers of the Buddhist kingdom—whose religion had taken root across the region along the Silk Road—made annual pilgrimages here to offer donations to the monks in return for their blessings. Then, in the eighth century, Islam came to the valley, and Buddhism began to wane. "In the third quarter of the ninth century, a Muslim conqueror destroyed everything—including the monastery," Tarzi says. "He gave Bamiyan the coup de grâce, but he couldn't destroy the giant Buddhas." Tarzi gazes toward the two empty niches, the one to the east 144 feet high and the one to the west 213 feet high. "It took the Taliban to do that."

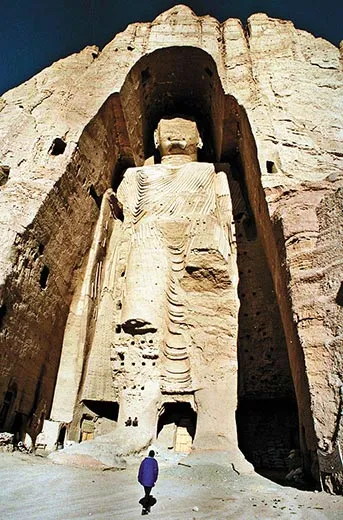

The Buddhas of Bamiyan, carved out of the cliff's malleable rock, long presided over this peaceful valley, protected by its near impregnable position between the Hindu Kush mountains to the north and the Koh-i-Baba range to the south. The monumental figures survived the coming of Islam, the scourge of Muslim conqueror Yaqub ibn Layth Saffari, the invasion and annihilation of virtually the entire Bamiyan population by Mongol warriors led by Genghis Khan in A.D. 1221 and the British-Afghan wars of the 19th century. But they couldn't survive the development of modern weaponry or a fanatical brand of Islam that gained ascendancy in Afghanistan following the war between the Soviet Union and the mujahedeen in the 1980s: almost ten years ago, in March 2001, after being denounced by Taliban fanatics as "false idols," the statues were pulverized with high explosives and rocket fire. It was an act that generated worldwide outrage and endures as a symbol of mindless desecration and religious extremism.

From almost the first moment the Taliban were driven from power at the end of 2001, art historians, conservationists and others have dreamed of restoring the Buddhas. Tarzi, however, has another idea. Somewhere in the shadow of the niches, he believes, lies a third Buddha—a 1,000-foot-long reclining colossus built at roughly the same time as the standing giants. His belief is based on a description written 1,400 years ago by a Chinese monk, Xuanzang, who visited the kingdom for several weeks. Tarzi has spent seven years probing the ground beneath the niches in search of the fabled statue. He has uncovered seven monasteries, fragments of a 62-foot-long reclining Buddha and many pieces of pottery and other Buddhist relics.

But other scholars say the Chinese monk may have mistaken a rock formation for the sculpture or was confused about the Buddha's location. Even if the reclining Buddha once existed, some hypothesize that it crumbled into dust centuries ago. "The Nirvana Buddha"—so called because the sleeping Buddha is depicted as he was about to enter the transcendent state of Nirvana—"remains one of archaeology's greatest mysteries," says Kazuya Yamauchi, an archaeologist with the Japan Center for International Cooperation in Conservation, who has carried out his own search for it. "It is the dream of archaeologists to find it."

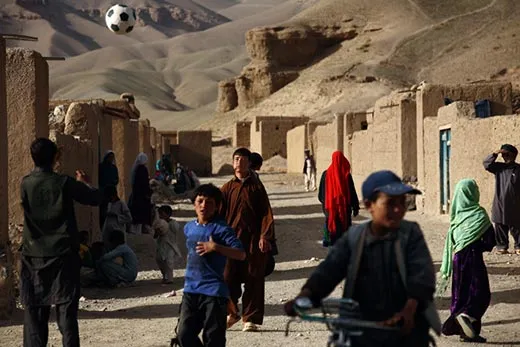

Time may be running out. Ever since U.S., coalition and Afghan Northern Alliance forces pushed the Taliban out of Afghanistan, remote Bamiyan—dominated by ethnic Hazaras who defied the Pashtun-dominated Taliban regime and suffered massacres at their hands—has been an oasis of tranquillity. But this past August, insurgents, likely Taliban, ambushed and killed a New Zealand soldier in northern Bamiyan—the first killing of a soldier in the province since the beginning of the war. "If the Taliban grows stronger elsewhere in Afghanistan, they could enter Bamiyan from different directions," says Habiba Sarabi, governor of Bamiyan province and the country's sole female provincial leader. Residents of Bamiyan—as well as archaeologists and conservationists—have lately been voicing the fear that even if new, reconstructed Buddhas rise in the niches, the Taliban would only blow them up again.

To visit Tarzi on his annual seven-week summer dig in Bamiyan, the photographer Alex Masi and I left Kabul at dawn in a Land Cruiser for a 140-mile, eight-hour journey on a dirt road on which an improvised explosive device had struck a U.N. convoy only days before. The first three hours, through Pashtun territory, were the riskiest. We drove without stopping, slumped low in our seats, wary of being recognized as foreigners. After snaking through a fertile river valley hemmed in by jagged granite and basalt peaks, we arrived at a suspension bridge marking the start of Hazara territory. "The security situation is now fine," our driver told us. "You can relax."

At the opening of the Bamiyan Valley, we passed a 19th-century mud fort and an asphalt road, part of a $200 million network under construction by the U.S. government and the Asian Development Bank. Then the valley widened to reveal a scene of breathtaking beauty: golden fields of wheat, interspersed with green plots of potato and bordered by the snowcapped, 18,000-foot peaks of the Hindu Kush and stark sandstone cliffs to the north. Finally we came over a rise and got our first look at the gaping cavities where the giant Buddhas once stood.

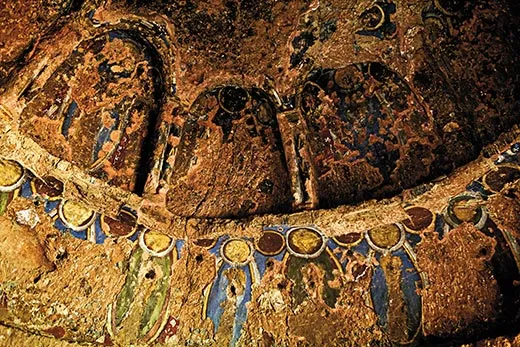

The vista was probably not much different from that which greeted Xuanzang, the monk who had left his home in eastern China in A.D. 629 and followed the Silk Road west across the Taklamakan Desert, arriving in Bamiyan several years later. Xuanzang was welcomed into a prosperous Buddhist enclave that had existed for some 500 years. There, cut from the cliffs, stood the greatest of the kingdom's symbols: a 180-foot-tall western Buddha and its smaller 125-foot-tall eastern counterpart—both gilded, decorated with lapis lazuli and surrounded by colorful frescoes depicting the heavens. The statues wore masks of wood and clay that in the moonlight conveyed the impression of glowing eyes, perhaps because they were embedded with rubies. Their bodies were draped in stucco tunics of a style worn by soldiers of Alexander the Great, who had passed through the region on his march to the Khyber Pass almost 1,000 years before. "[Their] golden hues sparkle on every side, and [their] precious ornaments dazzle the eyes by their brightness," wrote Xuanzang.

A member of a branch of Afghanistan's royal family, Tarzi first visited the Buddhas as an archaeology student in 1967. (He would earn a degree from the University of Strasbourg, in France, and become a prominent art historian and archaeologist in Kabul.) During the next decade, he returned to Bamiyan repeatedly to survey restoration work; the masks and some of the stucco garments had eroded away or been looted centuries earlier; the Buddhas were also crumbling.

"I visited every square inch of Bamiyan," he told me. It was during this time, he said, that he became convinced, based on Xuanzang's description, of the existence of a third Buddha. The monk mentioned a second monastery, in addition to the Royal Monastery, which is near the western Buddha. Inside it, he wrote, "there is a figure of Buddha lying in a sleeping position, as when he attained Nirvana. The figure is in length about 1,000 feet or so."

In 1978, a coup led by radical Marxists assassinated Afghanistan's first president; Tarzi's search for the sleeping Buddha was put on hold. Believing his life was in danger, Tarzi fled the country. "I left for Paris and became a refugee," he told me. He worked as a waiter in a restaurant in Strasbourg, married twice and had three children—daughters Nadia and Carole, and son David. Tarzi began teaching archaeology and became a full professor at the University of Strasbourg.

Back in Bamiyan, trouble was brewing. After several failed attempts to conquer the province, Taliban forces cut deals with Tajik and Hazara military leaders and marched in unopposed in September 1998. Many Hazara fled just ahead of the occupation. My interpreter, Ali Raza, a 26-year-old Hazara who grew up in the shadow of the eastern Buddha and played among the giant statues as a child, remembers his father calling the family together one afternoon. "He said, 'You must collect your clothes; we have to move as soon as possible, because the Taliban have arrived. If they don't kill us, we will be lucky.'" They gathered their mules and set out on foot, hiking south over snowy mountain passes to neighboring Maidan Wardak province; Raza later fled to Iran. The family didn't return home for five years.

In February 2001, Al Qaeda-supporting Taliban radicals, having won a power struggle with moderates, condemned the Buddhas as "idolatrous" and "un-Islamic" and announced their intention to destroy them. Last-ditch pleas by world leaders to Mullah Omar, the Taliban's reclusive, one-eyed leader, failed. During the next month, the Taliban—with the help of Arab munitions experts—used artillery shells and high explosives to destroy both figures. A Hazara construction worker I'll call Abdul, whom I met outside an unfinished mosque in the hills above Bamiyan, told me that the Taliban had conscripted him and 30 other Hazaras to lay plastic explosives on the ground beneath the larger Buddha's feet. It took three weeks to bring down the statue, Abdul told me. Then "the Taliban celebrated by slaughtering nine cows." Koichiro Matsuura, the head of UNESCO, the U.N.'s cultural organization, declared it "abominable to witness the cold and calculated destruction of cultural properties which were the heritage of...the whole of humanity." U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell deemed it a "tragedy."

Tarzi was in Strasbourg when he heard the news. "I watched it on television, and I said, 'This is not possible. Lamentable,'" he said.

Over lunch in the house he rents each summer in Bamiyan, he recounted the campaign he waged to return to Afghanistan after U.S. Special Forces and the Northern Alliance drove Osama bin Laden's protectors from power. In 2002, with the help of acquaintances such as the French philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, Tarzi persuaded the French government to give him funding (it has ranged from the equivalent of $40,000 to $50,000 a year) to search for the third Buddha. He flew to Bamiyan in July of that year and announced to a fiercely territorial warlord who had taken charge of the area that he planned to begin excavations. Tarzi was ordered to leave at once. "There was no real government in place, and I had nothing in writing. [Afghan] President [Hamid] Karzai wasn't aware of the mission. So I went back to France." The following year, Tarzi returned to Kabul, where Karzai received him warmly and gave a personal guarantee of safe passage.

One morning, I joined Tarzi in a tent beside the excavation site; we walked along a gully where some digging was going on. During his first excavation, in 2003, he told me with a touch of bravado, "The valley was filled with mines, but I wasn't afraid. I said, 'Follow me, and if I explode, you can take a different route.' And I took out a lot of mines myself, before the de-mining teams came here." Tarzi stopped before a second excavation pit and called to one of his diggers, a thin, bearded Hazara man who walked with a slight limp. The man, Tarzi told me, had lost both legs to a mine five years ago. "He was blown up just above where we're standing now, next to the giant Buddha," he added, as I shifted nervously. "We fitted him with prostheses, and he went back to work."

The archaeologist and I climbed into a minibus and drove to a second excavation site, just below the eastern niche where the smaller Buddha stood. He halted before the ruins of a seventh-century stupa, or relic chamber, a heap of clay and conglomerate rock. "This is where we started digging back in 2003, because the stupa was already exposed," Tarzi said. "It corresponded with Xuanzang's description, 'east of the Royal Monastery.' I thought at the beginning that the Buddha would be lying here, underneath the wheat fields. So I dug here, and I found a lot of ceramics, sculptures, but no Buddha."

Tarzi now gazed at the stupa with dismay. The 1,400-year-old ruin was covered with socks, shirts, pants and underwear, laundry laid out to dry by families living in nearby grottoes. "Please take a picture of the laundry drying on top of my stupa," he told one of the five University of Strasbourg graduate students who had joined him for the summer. Tarzi turned toward the cliff face, scanning the rough ground at its base. "If the great Buddha exists," he said, "it's there, at the foot of the great cliffs."

Not everyone is convinced. To be sure, Xuanzang's account is widely accepted. "He was remarkably accurate," says Nancy Dupree, an American expert on Afghan art and culture who has lived in Kabul for five decades. "The fact that he mentioned it means that there must have been something there." Kosaku Maeda, a retired professor of archaeology in Tokyo and one of the world's leading experts on the Bamiyan Valley, agrees that the monk probably did see a Sleeping Buddha. But Maeda believes that the figure, which was likely made of clay, would have crumbled into dust centuries ago. "If you think of a 1,000-foot-long reclining Buddha, then it would require 100 to 130 feet in height," he said. "You should see such a hill. But there is nothing." Kazuya Yamauchi, the Japanese archaeologist, believes Xuanzang's description of the figure's location is ambiguous. He contends it lies in a different part of the valley, Shari-i-Gholghola, or the "City of Screams," where the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan massacred thousands of inhabitants.

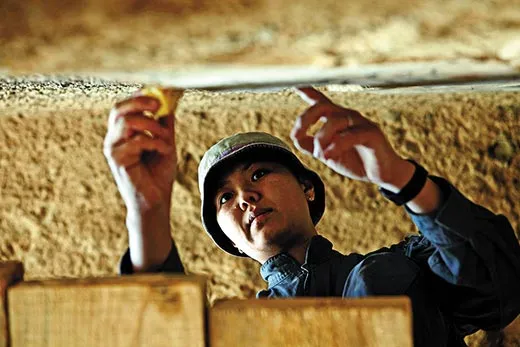

A short while after my outing with Tarzi, I climbed up some rickety metal scaffolding inside the eastern niche with Bert Praxenthaler, a Munich-based art historian and sculptor from the International Council on Monuments and Sites, a nongovernmental organization that receives UNESCO funding to shore up the niche walls, which were badly damaged by the Taliban blasts. In one of his first visits here some years ago, Praxenthaler recalls, he was rappelling inside the niche when he realized it was about to cave in. "It is just mud and pebbles baked together over millions of years," he said. "It lacks a natural cement, so the stone is rather weak. One slight earthquake would have destroyed everything." Praxenthaler and his team pumped 20 tons of mortar into cracks and fissures in the niche, then drilled dozens of long steel rods into the walls to support it."They are now stable," he said. Pointing to some faint smudges on the rough wall, he added: "You can see traces of the fingers of Buddhist workers, from 1,500 years ago." Praxenthaler's work led him to some serendipitous discoveries, including a tiny fabric bag—"closed with rope and sealed with two stamps"—concealed in a crevice behind the giant Buddha at the time it was constructed. "We still haven't opened it yet," he told me. "We think there is a Buddhist relic inside." (Praxenthaler is organizing a research project that will examine the presumably fragile contents.)

Preservation of the niches—work on the western one is scheduled to begin soon—is the first step, Praxenthaler said, in what many hope will be the reconstitution of the destroyed statues. During the past decade, conservationists, artists and others have floated many proposals, ranging from constructing concrete replicas to leaving the niches empty. Hiro Yamagata, a Japanese artist based in California, suggested that laser images of the Buddhas be projected onto the cliff face—an idea later abandoned as too costly and impractical.

For his part, Praxenthaler supports a method known as anastylosis, which involves combining surviving pieces of the Buddhas with modern materials. "It would be a fragmented Buddha, with gaps and holes, and later, they could fill in the gaps in a suitable way," he said. This approach has gathered strong backing from Governor Sarabi, as well as from archaeologists and art conservators, but it may not be feasible: most of the original Buddhas were pulverized, leaving only a few recognizable fragments. In addition, few Afghan officials think it politically wise, given the Islamic fervor and xenophobic sentiment of much of the country, especially among the Pashtun, to embrace a project celebrating the country's Buddhist past. "Conservation is OK, but at the moment they are critical about what smells like rebuilding the Buddha," Praxenthaler said. Others, including Tarzi, believe the niches should remain empty. New Buddhas, says Nancy Dupree, would turn Bamiyan into "an amusement park, and it would be a desecration to the artists who created the originals. The empty niches have a poignancy all their own." Tarzi agrees. "Leave the two Buddha niches as two pages of history," he told me, "so that future generations will know that at a certain moment, folly triumphed over reason in Afghanistan."

The funding that Tarzi currently gets from the French government allows him and his graduate students to fly from Strasbourg to Bamiyan each July, pay the rent on his house and employ guards and a digging team. He says he has been under no pressure to hasten his search, but the longer the work continues, the greater the likelihood his benefactors will run out of patience. "I've discovered sculptures, I've discovered the stupa, I've discovered the monasteries, I've developed a panorama of Bamiyan civilization from the first century to the arrival of Genghis Khan," he says. "The scientific results have been good."

Tarzi also continues to enjoy support from Afghan officials and many of his peers. "Tarzi is a well-educated, experienced Afghan archaeologist, and we need as many of those as we can get," says Brendan Cassar, the Kabul-based cultural specialist for UNESCO, which declared Bamiyan a World Heritage site in 2003. Nancy Dupree told me that Tarzi "wants to return something to Afghans to bolster their confidence and their belief [in the power of] their heritage. It's more than archaeology for him." But his ultimate goal, she fears, may never be realized. "What he has done is not to be sniffed at, he's found things there, but whether he will find the reclining Buddha, I really doubt."

After seven years of searching, even Tarzi has begun to hedge his bets. "I still have hope," he told me as we walked through irrigated fields of potatoes at the edge of his eastern excavations. "But I'm getting older—and weaker. Another three years, then I'll be finished."

Joshua Hammer reports from his base in Berlin. Photographer Alex Masi travels the world on assignment from London.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)