Shooting the American Dream in Suburbia

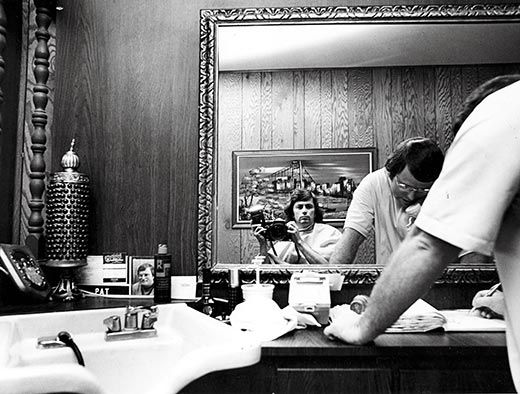

Bill Owens was seeking a fresh take on suburban life when he spotted a plastic-rifle-toting boy named Richie Ferguson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Indelible-Bill-Owens-photo-of-Richie-Ferguson-631.jpg)

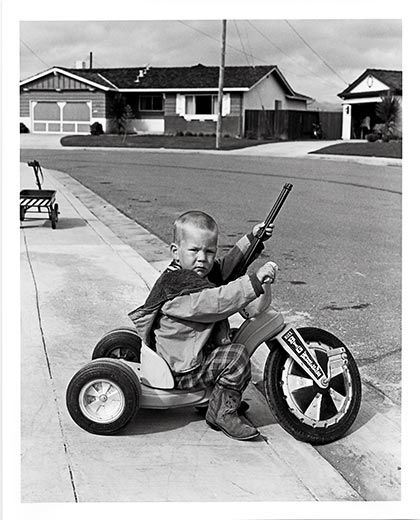

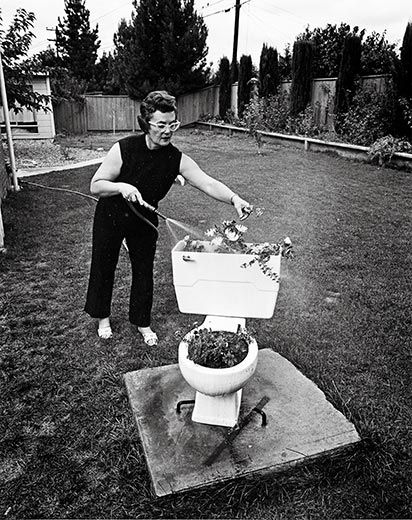

Bill Owens spent the late 1960s and early ’70s as a photographer for the Livermore Independent News, a thrice-weekly newspaper serving towns and communities east of San Francisco Bay, some of which were being swallowed by new housing developments. In those clusters of cookie-cutter tract houses, freshly painted and sodded, Owens faced a daunting task.

“I worked all week taking pictures for the newspaper, which often sent me to places where there weren’t any images,” Owens recalls. “But I still had to come back with a picture.”

Over time, Owens got to know the people in the new houses, and he discovered their devotion to the American dream—“three kids, the dog, the station wagon, the boat,” as he puts it. On weekends, he made pictures for himself—most of them portraits that reflected that dream. Or not. “I would go to houses in the East Bay where sometimes there was just no picture,” he told me. “I thought of those as ‘friend stops.’ ”

One day in 1971, he was leaving just such a stop in the town of Dublin when he spotted, in the next-door driveway, a crew-cut kid in cowboy boots riding a Big Wheel and holding a plastic rifle. He recognized the lad as 4-year-old Richie Ferguson. “The body language is just right,” Owens would later tell an interviewer, “and I didn’t pose him. I just said, ‘Richie!’—bang, took the picture—and you’re done.”

The Ferguson portrait became one of the most evocative images in Suburbia, a collection Owens published in 1972 to considerable acclaim. (Most recently, the picture was added to a new edition of Ken Light’s Witness in Our Time: Working Lives of Documentary Photographers.) oberSoon private collectors and museums, including the Museums of Modern Art in San Francisco and New York City, were buying his work. Within the decade two sequels, Our Kind of People (1975) and Working (I Do it for the Money)(1977), followed. Owens is a “keen and sympathetic observer of the daily rituals of life amid tract homes,” the Los Angeles Times later wrote.

His portraits were not news, but given the style and the subject matter, they were definitely new: they personalized a national aspiration and gave treeless neighborhoods the feeling of pioneer settlements. The décor might seem odd and the subjects might appear a bit disoriented, but the pictures have a relaxed intimacy that invites the viewer to look these new suburbanites in the eye, not down at them.

Owens, who is now 72, grew up on a farm in Citrus Heights, near Sacramento. Coming from the same sort of agricultural community that the new developments were devouring, he might have resented their upwardly hopeful inhabitants, but he says he didn’t.

“My parents came through the Depression,” he told me. “They weren’t judgmental people, and I guess that was passed on to me.” Plus, his influences—Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee and Arthur Rothstein, as well as Edward Steichen’s landmark 1955 “Family of Man” exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York—were acutely empathetic.

Owens came to photography in a roundabout way: after flunking out of Chico State College (now California State University, Chico) in 1960, he hitchhiked around the world and spent two years as a Peace Corps volunteer in Jamaica (“I needed to go somewhere where they spoke English,” he says) before returning to Chico State to finish his degree in industrial arts. He then studied photography at San Francisco State College for three semesters before the Livermore Independent News found his name on a “seeking work” list in a local employment office.

In the 1980s, Owens gave up on photography. Or rather, he says, “pho- tography gave up on me. You can’t make a living as a photographer if you live in the suburbs.” He worked at odd jobs and eventually became a brewer and distiller of some note (he pioneered California’s brew-pub movement) and the author of several books on beer and spirits. “I used to make beer when I was in college,” he told me one recent afternoon, after serving a glass of his own whiskey at his house in the East Bay town of Hayward. He took up picture-taking again with the advent of digital photography and after Suburbia was republished in 1999.

In 2000, nearly 30 years after his first portrait of Richie Ferguson, Owens made a second one of him for the New York Times. Ferguson, now a 43-year-old electrician, lives with his wife, Deanna, and their two children, ages 8 and 6, in Dublin, about a mile from where Owens first met him. He has graduated to a truly big wheel, a flame-painted Harley-Davidson motorcycle—a gift from Deanna. “I’d ridden dirt bikes as a kid, and when I turned 30 I guess my wife decided it was time for the real thing,” he says.

Ferguson has no memory of Owens taking the now-famous portrait. “My family had an original [print of it],” he says, “but I didn’t think it was a big deal. Kids don’t think about those things. I guess, to me, he was just a guy taking pictures.”

Now the more recent portrait hangs on gallery walls along with the original. “Bill calls me when he has an exhibition, and my wife and I always go,” Ferguson says. “When people see me in the picture, they treat me like I’m famous.”

Frequent contributor Owen Edwards is, like Bill Owens and Richie Ferguson, a resident of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)