Sketching the Earliest Views of the New World

The watercolors that John White produced in 1585 gave England its first startling glimpse of America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/braveworld_dec08_631.jpg)

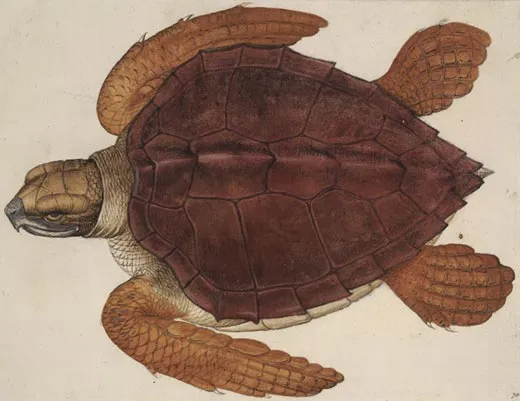

John White wasn't the most exacting painter that 16th-century England had to offer, or so his watercolors of the New World suggest. His diamondback terrapin has six toes instead of five; one of his native women, the wife of a powerful chief, has two right feet; his study of a scorpion looks cramped and rushed. In historical context, though, these quibbles seem unimportant: no Englishman had ever painted America before. White was burdened with unveiling a whole new realm.

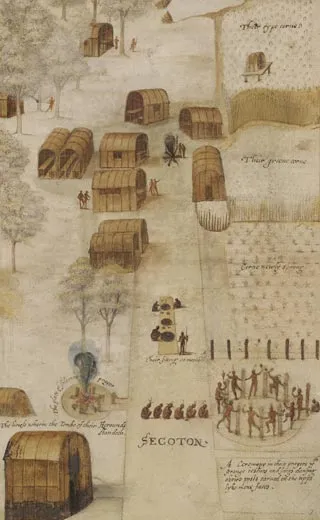

In the 1580s, England had yet to establish a permanent colonial foothold in the Western Hemisphere, while Spain's settlements in Central and South America were thriving. Sir Walter Raleigh sponsored a series of exploratory, and extraordinarily perilous, voyages to the coast of present-day North Carolina (then called Virginia, for the "Virgin Queen" Elizabeth) to drum up support for a colony among British investors. White, a gentleman-artist, braved skirmishes with Spanish ships and hurricanes to go along on five voyages between 1584 and 1590, including a 1585 expedition to found a colony on Roanoke Island off the Carolina coast. He would eventually become the governor of a second, doomed colony the British established there, but in 1585 he was commissioned to "drawe to life" the area's natural bounty and inhabitants. Who lived there, people back at court wanted to know; what did they look like; and what did they eat? This last question was vital, because Europe had recently entered a mini ice age and crops were suffering. Many of White's watercolors serve as a kind of pictorial menu. His scene of the local Algonquians fishing shows an enticing array of catches, including catfish, crab and sturgeon; other paintings dwell on cooking methods and corn cultivation.

"The message was: 'Come to this place where everything is neat and tidy and there is food everywhere!'" says Deborah Harkness, a science historian at the University of Southern California who studied White's watercolors and has written a book on Elizabethan London.

Occasionally, though, White seems to have been captivated by less digestible fare. He painted a magnificent watercolor study of a tiger swallowtail butterfly, and on a stop for provisions in the West Indies he rendered a "flye which in the night semeth a flame of fyer"—a firefly. These oddities, as much as his more practical illustrations, lodged in the Elizabethan imagination: engravings based on them were published in 1590, kindling interest in England's distant claims.

Today White's dozens of watercolors—the only surviving visual record of the land and peoples encountered by England's first settlers in America—remain vital documents for colonial scholars, who rejoiced when the works were exhibited earlier this year by the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh, the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Jamestown Settlement in Virginia. Owned by the British Museum, White's originals must be kept in storage, away from the damaging effects of light, for decades at a time; their transatlantic visit was a rarity.

Little is known about White's background. We do, however, know he married Thomasine Cooper in 1566 and they had at least two children. Before the 1585 expedition he may have been employed in Queen Elizabeth's Office of Revels, and he was almost certainly a gentleman—well educated and well connected; watercolor was considered a genteel medium, far more refined than oil. White sketched in graphite pencil and colored with indigo, vermilion and ground gold and silver leaf, among other pigments.

It's unclear when he actually completed his iconic American series, but he made his observations in the summer of 1585. After crossing the Atlantic, his ship stopped briefly in the West Indies, where White saw (and at some point painted)—in addition to the firefly—plantains, pineapples, flamingos and other curiosities. Soon afterward the ex-plorers sailed north to the Carolina coast.

As they built a crude fort on Roanoke, White went on excursions and began depicting the native Algonquian peoples. He detailed their ceremonies, ossuaries and meals of hulled corn. He carefully rendered the puma tail dangling from one chief's apron and a medicine man's pouch of tobacco or herbs. "White was documenting an unknown population," says Peter Mancall, an early American historian at the University of Southern California who delivered the opening lecture for the Yale exhibition. "He was trying to show how women carried their children, what a sorcerer looked like, how they fished."

But White probably also tweaked his Algonquian portraits. The swaggering poses are borrowed from European painting conventions, and one chief carries a gigantic bow that, according to the catalog, "would have reminded any English person looking at it of the similarity between English soldiers and Indian warriors." Other scenes, posed or not, were likely painted with investors in mind. An Algonquian chief, for instance, wears a large copper pendant, signaling that the precious metal was to be found in the New World. Scholars believe this may be Wingina, the "King of Roanoke," who was beheaded not long after White's 1585 visit because an English commander saw him as a threat. (Indeed, the chief probably did not appreciate the colonists' demands on his village's food stores.) On paper, however, the chief's expression is pleasant, perhaps even amused. There is almost no evidence of any English presence in the watercolors. Though tensions with the Indians had started to mount, White portrays an untouched world. This may have been a practical decision on his part: the British already knew what colonists looked like. But, in light of the Algonquians' eventual fate (they would soon be decimated by what they called "invisible bullets"—white men's diseases), the absence of any Europeans is also ominous. The only discernible sign of their arrival in Roanoke is a tiny figure in the arms of an Algonquian girl: a doll in Elizabethan costume.

The girl "is looking up at her mother as if to say, 'Is this someone I could meet or even possibly be?'" says Joyce Chaplin, an American history professor at Harvard University who wrote an essay for the exhibition catalog. "It's very poignant."

White's paintings and the text accompanying them (written by Thomas Harriot, a scientist also on the 1585 voyage) are virtually all that remain of that time and place. After presenting his paintings in England to an unknown patron, possibly Raleigh or the queen, White returned to Roanoke in 1587 as governor, bringing with him more than a hundred men, women and children. Their supplies quickly ran out, and White, leaving members of his own family on the island, returned to England for assistance. But English relations with the great sea power Spain had deteriorated, and as the Armada threatened, he was unable to get back to Roanoke until 1590. By then, the English settlers had vanished, and the mystery of the "Lost Colony" was born. It's still unclear whether the settlers died or moved south to assimilate with a friendly native village. At any rate, because of rough seas, the approaching hurricane season and damage to his ship, White was able to search for the colonists for only about a day and never learned the fate of his daughter, Elinor, his son-in-law, Ananias Dare, and his granddaughter, Virginia, the first English child born in North America.

Such hardships, British Museum curator Kim Sloan writes in the show's catalog, lead one to wonder "what drove this man even to begin, never mind persist in, an enterprise that lost him his family, his wealth and very nearly his life." White's own last years are also lost to history: the final record of his life is a letter from 1593 to Richard Hakluyt (an English author who wrote about voyages to America), in which White sums up his last trip—"as lucklesse to many, as sinister to my selfe."

Today some of the plants and animals White painted, including a glaring loggerhead turtle, are threatened. Even the watercolors themselves are in precarious condition, which is why the British Museum displays them only once every few decades. In the mid-19th century they sustained heavy water damage in a Sotheby's auction house fire. Chemical changes in the silver pigments have turned them black, and other colors are mere shadows of what they once were.

The originals were engraved and copied countless times, and versions showed up in everything from costume books to encyclopedias of insects. The paintings of Indians became so entrenched in the English consciousness that they were difficult to displace. Generations of British historians used White's illustrations to describe Native Americans, even those from other regions. Later painters, including the 18th-century natural history artist Mark Catesby, modeled their works on versions of White's watercolors.

Britain did not establish a permanent colony until Jamestown in 1607, nearly two decades after White left America for the last time. Jamestown was a settlement of businessmen: there was no gentleman-artist on hand to immortalize the native people there. In fact, the next major set of American Indian portraits would not appear until George Catlin painted the peoples of the Great Plains more than 200 years later.

Magazine staff writer Abigail Tucker reported on rare color photographs from the Korean War in the November issue.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.