The Great Wall of China Is Under Siege

China’s ancient 4,000-mile barrier, built to defend the country against invaders, is under renewed attack

The Great Wall of China snakes along a ridge in front of me, its towers and ramparts creating a panorama that could have been lifted from a Ming dynasty scroll. I should be enjoying the view, but I'm focused instead on the feet of my guide, Sun Zhenyuan. Clambering behind him across the rocks, I can't help but marvel at his footwear. He is wearing cloth slippers with wafer-thin rubber soles, better suited to tai chi than a trek along a mountainous section of the wall.

Sun, a 59-year-old farmer turned preservationist, is conducting a daily reconnaissance along a crumbling 16th-century stretch of the wall overlooking his home, Dongjiakou village, in eastern Hebei Province. We stand nearly 4,000 twisting miles from where the Great Wall begins in China's western deserts—and only 40 miles from where it plunges into the Bohai Sea, the innermost gulf of the Yellow Sea on the coast of northeast China. Only 170 miles distant, but a world away, lies Beijing, where seven million spectators are about to converge for the Summer Olympics. (The massive earthquake that hit southern China in May did not damage the wall, although tremors could be felt on sections of it near Beijing.)

Hiking toward a watchtower on the ridge above us, Sun sets a brisk pace, stopping only to check his slippers' fraying seams. "They cost only ten yuan [$1.40]," he says, "but I wear out a pair every two weeks." I do a quick calculation: over the past decade, Sun must have burned through some 260 pairs of shoes as he's carried out his crusade to protect one of China's greatest treasures—and to preserve his family's honor.

Twenty-one generations ago, in the mid-1500s, Sun's ancestors arrived at this hilly outpost wearing military uniforms (and, presumably, sturdier footwear). His forebears, he says, were officers in the Ming imperial army, part of a contingent that came from southern China to shore up one of the wall's most vulnerable sections. Under the command of General Qi Jiguang, they added to an earlier stone and earthen barrier, erected nearly two centuries before at the beginning of the Ming dynasty. Qi Jiguang also added a new feature—watchtowers—at every peak, trough and turn. The towers, built between 1569 and 1573, enabled troops to shelter in secure outposts on the wall itself as they awaited Mongol attacks. Even more vitally, the towers also functioned as sophisticated signaling stations, enabling the Ming army to mitigate the wall's most impressive, but daunting, feature: its staggering length.

As we near the top of the ridge, Sun quickens his pace. The Great Wall looms directly above us, a 30-foot-high face of rough-hewed stone topped by a two-story watchtower. When we reach the tower, he points at the Chinese characters carved above the arched doorway, which translate to Sunjialou, or Sun Family Tower. "I see this as a family treasure, not just a national treasure," Sun says. "If you had an old house that people were damaging, wouldn't you want to protect it?"

He gazes toward the horizon. As he conjures up the dangers that Ming soldiers once faced, the past and present seem to intertwine. "Where we're standing is the edge of the world," he says. "Behind us is China. Out there"—he gestures toward craggy cliffs to the north—"the land of the barbarians."

Few cultural landmarks symbolize the sweep of a nation's history more powerfully than the Great Wall of China. Constructed by a succession of imperial dynasties over 2,000 years, the network of barriers, towers and fortifications expanded over the centuries, defining and defending the outer limits of Chinese civilization. At the height of its importance during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Great Wall is believed to have extended some 4,000 miles, the distance from New York to Milan.

Today, however, China's most iconic monument is under assault by both man and nature. No one knows just how much of the wall has already been lost. Chinese experts estimate that more than two-thirds may have been damaged or destroyed, while the rest remains under siege."The Great Wall is a miracle, a cultural achievement not just for China but for humanity," says Dong Yaohui, president of the China Great Wall Society. "If we let it get damaged beyond repair in just one or two generations, it will be our lasting shame."

The barbarians, of course, have changed. Gone are the invading Tatars (who broke through the Great Wall in 1550), Mongols (whose raids kept Sun's ancestors occupied) and Manchus (who poured through uncontested in 1644). Today's threats come from reckless tourists, opportunistic developers, an indifferent public and the ravages of nature. Taken together, these forces—largely byproducts of China's economic boom—imperil the wall, from its tamped-earth ramparts in the western deserts to its majestic stone fortifications spanning the forested hills north of Beijing, near Badaling, where several million tourists converge each year.

From its origins under the first emperor in the third century B.C., the Great Wall has never been a single barrier, as early Western accounts claimed. Rather, it was an overlapping maze of ramparts and towers that was unified only during frenzied Ming dynasty construction, beginning in the late 1300s. As a defense system, the wall ultimately failed, not because of intrinsic design flaws but because of the internal weaknesses—corruption, cowardice, infighting—of various imperial regimes. For three centuries after the Ming dynasty collapsed, Chinese intellectuals tended to view the wall as a colossal waste of lives and resources that testified less to the nation's strength than to a crippling sense of insecurity. In the 1960s, Mao Zedong's Red Guards carried this disdain to revolutionary excess, destroying sections of an ancient monument perceived as a feudal relic.

Nevertheless, the Great Wall has endured as a symbol of national identity, sustained in no small part by successive waves of foreigners who have celebrated its splendors—and perpetuated its myths. Among the most persistent fallacies is that it is the only man-made structure visible from space. (In fact, one can make out a number of other landmarks, including the pyramids. The wall, according to a recent Scientific American report, is visible only "from low orbit under a specific set of weather and lighting conditions.") Mao's reformist successor, Deng Xiaoping, understood the wall's iconic value. "Love China, Restore the Great Wall," he declared in 1984, initiating a repair and reconstruction campaign along the wall north of Beijing. Perhaps Deng sensed that the nation he hoped to build into a superpower needed to reclaim the legacy of a China whose ingenuity had built one of the world's greatest wonders.

Today, the ancient monument is caught in contemporary China's contradictions, in which a nascent impulse to preserve the past confronts a headlong rush toward the future. Curious to observe this collision up close, I recently walked along two stretches of the Ming-era wall, separated by a thousand miles—the stone ramparts undulating through the hills near Sun's home in eastern Hebei Province and an earthen barrier that cuts across the plains of Ningxia in the west. Even along these relatively well-preserved sections, threats to the wall—whether by nature or neglect, by reckless industrial expansion or profit-hungry tour operators—pose daunting challenges.

Yet a small but increasingly vocal group of cultural preservationists act as defenders of the Great Wall. Some, like Sun, patrol its ramparts. Others have pushed the government to enact new laws and have initiated a comprehensive, ten-year GPS survey that may reveal exactly how long the Great Wall once was—and how much of it has been lost.

In northwest China's Ningxia region, on a barren desert hilltop, a local shepherd, Ding Shangyi, and I gaze out at a scene of austere beauty. The ocher-colored wall below us, constructed of tamped earth instead of stone, lacks the undulations and crenelations that define the eastern sections. But here, a simpler wall curves along the western flank of the Helan Mountains, extending across a rocky moonscape to the far horizon. For the Ming dynasty, this was the frontier, the end of the world—and it still feels that way.

Ding, 52, lives alone in the shadow of the wall near Sanguankou Pass. He corrals his 700 sheep at night in a pen that abuts the 30-foot-tall barrier. Centuries of erosion have rounded the wall's edges and pockmarked its sides, making it seem less a monumental achievement than a kind of giant sponge laid across gravelly terrain. Although Ding has no idea of the wall's age—"a hundred years old," Ding guesses, off by about three and a half centuries—he reckons correctly that it was meant to "repel the Mongols."

From our hilltop, Ding and I can make out the remnants of a 40-foot-high tower on the flats below Sanguankou. Relying on observation sites like this one, soldiers transmitted signals from the front lines back to the military command. Employing smoke by day and fire at night, they could send messages down the line at a rate of 620 miles per day—or about 26 miles per hour, faster than a man on horseback.

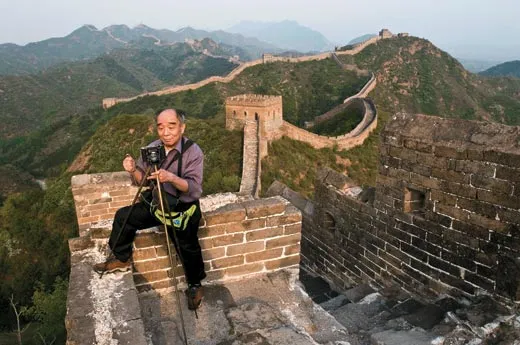

According to Cheng Dalin, a 66-year-old photographer and a leading authority on the wall, the signals also conveyed the degree of threat: an incursion of 100 men required one lighted beacon and a round of cannon fire, he says, while 5,000 men merited five plumes of smoke and five cannon shots. The tallest, straightest columns of smoke were produced by wolf dung, which explains why, even today, the outbreak of war is described in literary Chinese as "a rash of wolf smoke across the land."

Nowhere are threats to the wall more evident than in Ningxia. The most relentless enemy is desertification—a scourge that began with construction of the Great Wall itself. Imperial policy decreed that grass and trees be torched within 60 miles of the wall, depriving enemies of the element of surprise. Inside the wall, the cleared land was used for crops to sustain soldiers. By the middle of the Ming dynasty, 2.8 million acres of forest had been converted to farmland. The result? "An environmental disaster," says Cheng.

Today, with the added pressures of global warming, overgrazing and unwise agricultural policies, China's northern desert is expanding at an alarming rate, devouring approximately one million acres of grassland annually. The Great Wall stands in its path. Shifting sands may occasionally expose a long-buried section—as happened in Ningxia in 2002—but for the most part, they do far more harm than good. Rising dunes swallow entire stretches of wall; fierce desert winds shear off its top and sides like a sandblaster. Here, along the flanks of the Helan Mountains, water, ironically enough, is the greatest threat. Flash floods run off denuded highlands, gouging out the wall's base and causing upper levels to teeter and collapse.

At Sanguankou Pass, two large gaps have been blasted through the wall, one for a highway linking Ningxia to Inner Mongolia—the wall here marks the border—and the other for a quarry operated by a state-owned gravel company. Trucks rumble through the breach every few minutes, picking up loads of rock destined to pave Ningxia's roads. Less than a mile away, wild horses lope along the wall, while Ding's sheep forage for roots on rocky hills.

The plundering of the Great Wall, once fed by poverty, is now fueled by progress. In the early days of the People's Republic, in the 1950s, peasants pilfered tamped earth from the ramparts to replenish their fields, and stones to build houses. (I recently visited families in the Ningxia town of Yanchi who still live in caves dug out of the wall during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76.) Two decades of economic growth have turned small-scale damage into major destruction. In Shizuishan, a heavily polluted industrial city along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia, the wall has collapsed because of erosion—even as the Great Wall Industrial Park thrives next door. Elsewhere in Ningxia, construction of a paper mill in Zhongwei and a petrochemical factory in Yanchi has destroyed sections of the wall.

Regulations enacted in late 2006—focusing on protecting the Great Wall in its entirety—were intended to curb such abuses. Damaging the wall is now a criminal offense. Anyone caught bulldozing sections or conducting all-night raves on its ramparts—two of many indignities the wall has suffered—now faces fines. The laws, however, contain no provisions for extra personnel or funds. According to Dong Yaohui, president of the China Great Wall Society, "The problem is not lack of laws, but failure to put them into practice."

Enforcement is especially difficult in Ningxia, where a vast, 900-mile-long network of walls is overseen by a cultural heritage bureau with only three employees. On a recent visit to the region, Cheng Dalin investigated several violations of the new regulations and recommended penalties against three companies that had blasted holes in the wall. But even if the fines were paid—and it's not clear that they were—his intervention came too late. The wall in those three areas had already been destroyed.

Back on the hilltop, I ask Ding if watching the wall's slow disintegration provokes a sense of loss. He shrugs and offers me a piece of guoba, the crust of scorched rice scraped from the bottom of a pot. Unlike Sun, my guide in Hebei, Ding confesses that he has no special feeling for the wall. He has lived in a mud-brick shack on its Inner Mongolian side for three years. Even in the wall's deteriorated condition, it shields him from desert winds and provides his sheep with shelter. So Ding treats it as nothing more, or less, than a welcome feature in an unforgiving environment. We sit in silence for a minute, listening to the sound of sheep ripping up the last shoots of grass on these rocky hills. This entire area may be desert soon, and the wall will be more vulnerable than ever. It's a prospect that doesn't bother Ding. "The Great Wall was built for war," he says. "What's it good for now?"

A week later and a thousand miles away in Shandong Province, I stare at a section of wall zig-zagging up a mountain. From battlements to watchtowers, the structure looks much like the Ming wall at Badaling. On closer inspection, however, the wall here, near the village of Hetouying, is made not of stone but of concrete grooved to mimic stone. The local Communist Party secretary who oversaw the project from 1999 on must have figured that visitors would want a wall like the real thing at Badaling. (A modest ancient wall, constructed here 2,000 years before the Ming, was covered over.)

But there are no visitors; the silence is broken only when a caretaker arrives to unlock the gate. A 62-year-old retired factory worker, Mr. Fu—he gives only his surname—waives the 30-cent entrance fee. I climb the wall to the top of the ridge, where I'm greeted by two stone lions and a 40-foot-tall statue of Guanyin, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. When I return, Mr. Fu is waiting to tell me just how little mercy the villagers have received. Not long after factories usurped their farmland a decade ago, he says, the party secretary persuaded them to invest in the reproduction wall. Mr. Fu lost his savings. "It was a waste of money," he says, adding that I'm the first tourist to visit in months. "Officials talk about protecting the Great Wall, but they just want to make money from tourism."

Certainly the Great Wall is big business. At Badaling, visitors can buy Mao T-shirts, have their photo taken on a camel or sip a latte at Starbucks—before even setting foot on the wall. Half an hour away, at Mutianyu, sightseers don't even have to walk at all. After being disgorged from tour buses, they can ride to the top of the wall in a cable car.

In 2006 golfers promoting the Johnnie Walker Classic teed off from the wall at Juyongguan Pass outside Beijing. And last year the French-owned fashion house Fendi transformed the ramparts into a catwalk for the Great Wall's first couture extravaganza, a media-saturated event that offended traditionalists. "Too often," says Dong Yaohui, of the China Great Wall Society, "people see only the exploitable value of the wall and not its historical value."

The Chinese government has vowed to restrict commercialization, banning mercantile activities within a 330-foot radius of the wall and requiring wall-related revenue to be funneled into preservation. But pressure to turn the wall into a cash-generating commodity is powerful. Two years ago, a melee broke out along the wall on the border between Hebei and Beijing, as officials from both sides traded punches over who could charge tourist fees; five people were injured. More damaging than fists, though, have been construction crews that have rebuilt the wall at various points—including a site near the city of Jinan where fieldstone was replaced by bathroom tiles. According to independent scholar David Spindler, an American who has studied the Ming-era wall since 2002, "reckless restoration is the greatest danger."

The Great Wall is rendered even more vulnerable by a paucity of scholarship. Spindler is an exception. There is not a single Chinese academic—indeed, not a scholar at any university in the world—who specializes in the Great Wall; academia has largely avoided a subject that spans so many centuries and disciplines—from history and politics to archaeology and architecture. As a result, some of the monument's most basic facts, from its length to details of its construction, are unknown. "What exactly is the Great Wall?" asks He Shuzhong, founder and chairman of the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (CHP), a nongovernmental organization. "Nobody knows exactly where it begins or ends. Nobody can say what its real condition is."

That gap in knowledge may soon be closing. Two years ago, the Chinese government launched an ambitious ten-year survey to determine the wall's precise length and assess its condition. Thirty years ago, a preliminary survey team relied on little more than tape measures and string; today, researchers are using GPS and imaging technology. "This measuring is fundamental," says William Lindesay, a British preservationist who heads the Beijing-based International Friends of the Great Wall. "Only when we know exactly what is left of the Great Wall can we begin to understand how it might be saved."

As Sun Zhenyuan and I duck through the arched doorway of his family watchtower, his pride turns to dismay. Fresh graffiti scars the stone walls. Beer bottles and food wrappers cover the floor. This kind of defilement occurs increasingly, as day-trippers drive from Beijing to picnic on the wall. In this case, Sun believes he knows who the culprits are. At the trail head, we had passed two obviously inebriated men, expensively attired, staggering down from the wall with companions who appeared to be wives or girlfriends toward a parked Audi sedan. "Maybe they have a lot of money," Sun says, "but they have no culture."

In many villages along the wall, especially in the hills northeast of Beijing, inhabitants claim descent from soldiers who once served there. Sun believes his ancestral roots in the region originated in an unusual policy shift that occurred nearly 450 years ago, when Ming General Qi Jiguang, trying to stem massive desertions, allowed soldiers to bring wives and children to the frontlines. Local commanders were assigned to different towers, which their families treated with proprietary pride. Today, the six towers along the ridge above Dongjiakou bear surnames shared by nearly all the village's 122 families: Sun, Chen, Geng, Li, Zhao and Zhang.

Sun began his preservationist crusade almost by accident a decade ago. As he trekked along the wall in search of medicinal plants, he often quarreled with scorpion hunters who were ripping stones from the wall to get at their prey (used in the preparation of traditional medicines). He also confronted shepherds who allowed their herds to trample the ramparts. Sun's patrols continued for eight years before the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center began sponsoring his work in 2004. CHP chairman He Shuzhong hopes to turn Sun's lonely quest into a full-fledged movement. "What we need is an army of Mr. Suns," says He. "If there were 5,000 or 10,000 like him, the Great Wall would be very well protected."

Perhaps the greatest challenge lies in the fact that the wall extends for long stretches through sparsely populated regions, such as Ningxia, where few inhabitants feel any connection to it—or have a stake in its survival. Some peasants I met in Ningxia denied that the tamped-earth barrier running past their village was part of the Great Wall, insisting that it looked nothing like the crenelated stone fortifications of Badaling they've seen on television. And a Chinese survey conducted in 2006 found that only 28 percent of respondents thought the Great Wall needed to be protected. "It's still difficult to talk about cultural heritage in China," says He, "to tell people that this is their own responsibility, that this should give them pride."

Dongjiakou is one of the few places where protection efforts are taking hold. When the local Funin County government took over the CHP program two years ago, it recruited 18 local residents to help Sun patrol the wall. Preservation initiatives like his, the government believes, could help boost the sagging fortunes of rural villages by attracting tourists who want to experience the "wild wall." As leader of his local group, Sun is paid about $120 per year; others receive a bit less. Sun is confident that his family legacy will continue into the 22nd generation: his teenage nephew now joins him on his outings.

From the entrance to the Sun Family Tower, we hear footsteps and wheezing. A couple of tourists—an overweight teenage boy and his underweight girlfriend—climb the last steps onto the ramparts. Sun flashes a government-issued license and informs them that he is, in effect, the constable of the Great Wall. "Don't make any graffiti, don't disturb any stones and don't leave any trash behind," he says. "I have the authority to fine you if you violate any of these rules." The couple nods solemnly. As they walk away, Sun calls after them: "Always remember the words of Chairman Deng Xiaoping: ‘Love China, Restore the Great Wall!'"

As Sun cleans the trash from his family's watchtower, he spies a glint of metal on the ground. It's a set of car keys: the black leather ring is imprinted with the word "Audi." Under normal circumstances, Sun would hurry down the mountain to deliver the keys to their owners. This time, however, he'll wait for the culprits to hike back up, looking for the keys—and then deliver a stern lecture about showing proper respect for China's greatest cultural monument. Flashing a mischievous smile, he slides the keys into the pocket of his Mao jacket. It's one small victory over the barbarians at the gate.

Brook Larmer, formerly the Shanghai bureau chief for Newsweek, is a freelance writer who lives in Bangkok, Thailand. Photographer Mark Leong is based in Beijing.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.