The Scurlock Studio: Picture of Prosperity

For more than half a century the Scurlock Studio chronicled the rise of Washington’s black middle class

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Scurlock-Marian-Anderson-Lincoln-Memorial-631.jpg)

Long before a black family moved into the president’s quarters at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C. was an African-American capital: as far back as Reconstruction, black families made their way to the city on their migration north. By the turn of the 20th century, the District of Columbia had a strong and aspiring black middle class, whose members plied almost every trade in town. Yet in 1894, a black business leader named Andrew F. Hilyer noted an absence: “There is a splendid opening for a first class Afro-American photographer as we all like to have our pictures taken.”

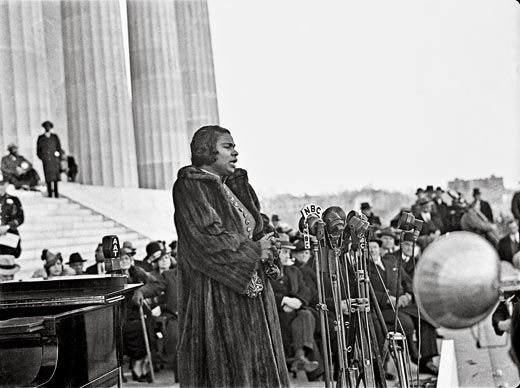

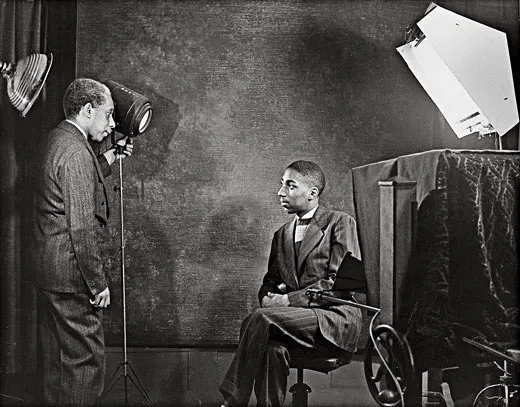

Addison Scurlock filled the bill. He had come to Washington in 1900 from Fayetteville, North Carolina, with his parents and two siblings. Although he was only 17, he listed “photographer” as his profession in that year’s census. After apprenticing with a white photographer named Moses Rice from 1901 to 1904, Scurlock started a small studio in his parents’ house. By 1911, he had opened a storefront studio on U Street, the main street of Washington’s African-American community. He put his best portraits in the front window.

“There’d be a picture of somebody’s cousin there,” Scurlock’s son George would recall much later, “and they would say, ‘Hey, if you can make him look that good, you can make me look better.’ ” Making all his subjects look good would remain a Scurlock hallmark, carried on by George and his brother Robert.

A Scurlock camera was “present at almost every significant event in the African-American community,” recalls former D.C. Councilwoman Charlene Drew Jarvis, whose father, Howard University physician Charles Drew, was a Scurlock subject many times. Dashing all over town—to baptisms and weddings, to balls and cotillions, to high-school graduations and to countless events at Howard, where he was the official photographer—Addison Scurlock became black Washington’s “photographic Boswell—the keeper of the visual memory of the community in all its quotidian ordinariness and occasional flashes of grandeur and moment,” says Jeffrey Fearing, a historian who is also a Scurlock relative.

The Scurlock Studio grew as the segregated city became a mecca for black artists and thinkers even before the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. U Street became known as “Black Broadway,” as its jazz clubs welcomed talents including Duke Ellington (who lived nearby), Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey. They and other entertainers received the Scurlock treatment, along with the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington; soon no black dignitary’s visit to Washington was complete without a Scurlock sitting. George Scurlock would say it took him a while to realize that his buddy Mercer Ellington’s birthday parties—with Mercer’s dad (a.k.a. the Duke) playing “Happy Birthday” at the piano—were anything special.

At a time when minstrel caricature was common, Scurlock’s pictures captured black culture in its complexity and showed black people as they saw themselves. “The Scurlock Studio and Black Washington: Picturing the Promise,” an exhibition presented through this month by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, features images of young ballerinas in tutus, of handsomely dressed families in front of fine houses and couples in gowns and white tie at the NAACP’s winter ball.

“You see these amazing strivers, you see these people who have acquired homes and businesses,” says Lonnie Bunch, director of the museum, whose permanent home on the National Mall is scheduled to open in 2015. (The current exhibition is at the National Museum of American History.) “In some ways I think the Scurlocks saw themselves as partners with Du Bois in...crafting a new vision of America, a vision where racial equality and racial improvement was possible.”

One 1931 image depicts the girls of Camp Clarissa Scott at Highland Beach, Maryland—a Chesapeake Bay vacation spot founded by blacks of means who had been barred from whites-only beaches. “It was nice, real nice,” says one of the campers, Phyllis Bailey Washington, now 90 and living in Silver Spring, Maryland. “In the evening we’d have singalongs and campfires and cookouts.”

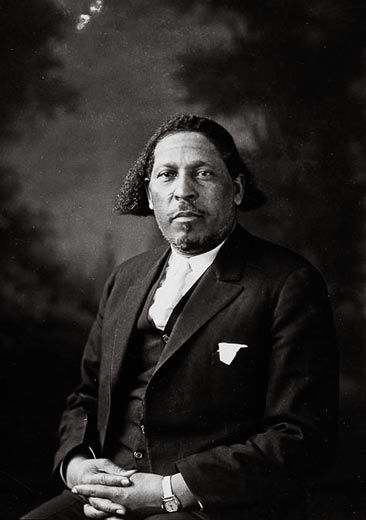

After the Scurlock brothers graduated from Howard (Robert in 1937 and George in 1941), they worked in the family business—Robert was trusted to photograph singer Marian Anderson’s famous 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial—and took it in new directions. From 1947 to 1951 they ran a photography school, where they briefly taught Jacqueline Bouvier (who would become the “Inquiring Camera Girl” for the Washington Times-Herald before marrying John F. Kennedy). Robert, in particular, began to show a photojournalistic streak, contributing pictures to Ebony magazine and the Afro-American, the Pittsburgh Courier and the Chicago Defender. When rioters beset Washington after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, he went into the streets with his camera.

The brothers bought the business from their father in 1963, the year before he died at age 81. They ran it with at times waning enthusiasm. Integration, while welcome and long overdue, gradually diluted their traditional client base as blacks found new places to work and live. And studio photography itself began to change. “Nowadays, in the era of fast turnaround, everybody wants to know how fast you can do it,” Robert told a reporter in 1990. “Nobody asks, ‘How good can you do it?’ ” George left the business in 1977 and made his living selling cars. He died in 2005 at age 85. After Robert’s death at age 77 in 1994, his widow, Vivian, closed the studio.

The discouragements of the later years did not prevent the Scurlocks from tending to their legacy, and in 1997, the Scurlock Studio Collection—some 250,000 negatives and 10,000 prints, plus cameras and other equipment—entered the Smithsonian Institution’s archives. “Due to its sheer size, the collection’s secrets are barely beginning to be uncovered,” Donna M. Wells and David E. Haberstich write in a catalog essay for “Picturing the Promise.”

But the more than 100 images now on exhibit hint at the scope and significance of the Scurlocks’ work. Throughout the bleakest days of segregation, with its privations and indignities, generations of black Washingtonians entered the Scurlock Studio confident they would be portrayed in the best light.

David Zax has written for Smithsonian on the photographers Emmet Gowin and Neal Slavin. He lives in New York City.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)