The Political History of Cap and Trade

How an unlikely mix of environmentalists and free-market conservatives hammered out the strategy known as cap-and-trade

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/pollution-power-plant-631.jpg)

John B. Henry was hiking in Maine's Acadia National Park one August in the 1980s when he first heard his friend C. Boyden Gray talk about cleaning up the environment by letting people buy and sell the right to pollute. Gray, a tall, lanky heir to a tobacco fortune, was then working as a lawyer in the Reagan White House, where environmental ideas were only slightly more popular than godless Communism. "I thought he was smoking dope," recalls Henry, a Washington, D.C. entrepreneur. But if the system Gray had in mind now looks like a politically acceptable way to slow climate change—an approach being hotly debated in Congress—you could say that it got its start on the global stage on that hike up Acadia's Cadillac Mountain.

People now call that system "cap-and-trade." But back then the term of art was "emissions trading," though some people called it "morally bankrupt" or even "a license to kill." For a strange alliance of free-market Republicans and renegade environmentalists, it represented a novel approach to cleaning up the world—by working with human nature instead of against it.

Despite powerful resistance, these allies got the system adopted as national law in 1990, to control the power-plant pollutants that cause acid rain. With the help of federal bureaucrats willing to violate the cardinal rule of bureaucracy—by surrendering regulatory power to the marketplace—emissions trading would become one of the most spectacular success stories in the history of the green movement. Congress is now considering whether to expand the system to cover the carbon dioxide emissions implicated in climate change—a move that would touch the lives of almost every American. So it's worth looking back at how such a radical idea first got translated into action, and what made it work.

The problem in the 1980s was that American power plants were sending up vast clouds of sulfur dioxide, which was falling back to earth in the form of acid rain, damaging lakes, forests and buildings across eastern Canada and the United States. The squabble about how to fix this problem had dragged on for years. Most environmentalists were pushing a "command-and-control" approach, with federal officials requiring utilities to install scrubbers capable of removing the sulfur dioxide from power-plant exhausts. The utility companies countered that the cost of such an approach would send them back to the Dark Ages. By the end of the Reagan administration, Congress had put forward and slapped down 70 different acid rain bills, and frustration ran so deep that Canada's prime minister bleakly joked about declaring war on the United States.

At about the same time, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) had begun to question its own approach to cleaning up pollution, summed up in its unofficial motto: "Sue the bastards." During the early years of command-and-control environmental regulation, EDF had also noticed something fundamental about human nature, which is that people hate being told what to do. So a few iconoclasts in the group had started to flirt with marketplace solutions: give people a chance to turn a profit by being smarter than the next person, they reasoned, and they would achieve things that no command-and-control bureaucrat would ever suggest.

The theory had been brewing for decades, beginning with early 20th-century British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou. He argued that transactions can have effects that don't show up in the price of a product. A careless manufacturer spewing noxious chemicals into the air, for instance, did not have to pay when the paint peeled off houses downwind—and neither did the consumer of the resulting product. Pigou proposed making the manufacturer and customer foot the bill for these unacknowledged costs—"internalizing the externalities," in the cryptic language of the dismal science. But nobody much liked Pigou's means of doing it, by having regulators impose taxes and fees. In 1968, while studying pollution control in the Great Lakes, University of Toronto economist John Dales hit on a way for the costs to be paid with minimal government intervention, by using tradable permits or allowances.

The basic premise of cap-and-trade is that government doesn't tell polluters how to clean up their act. Instead, it simply imposes a cap on emissions. Each company starts the year with a certain number of tons allowed—a so-called right to pollute. The company decides how to use its allowance; it might restrict output, or switch to a cleaner fuel, or buy a scrubber to cut emissions. If it doesn't use up its allowance, it might then sell what it no longer needs. Then again, it might have to buy extra allowances on the open market. Each year, the cap ratchets down, and the shrinking pool of allowances gets costlier. As in a game of musical chairs, polluters must scramble to match allowances to emissions.

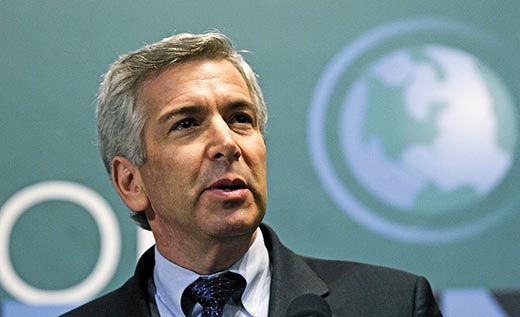

Getting all this to work in the real world required a leap of faith. The opportunity came with the 1988 election of George H.W. Bush. EDF president Fred Krupp phoned Bush's new White House counsel—Boyden Gray—and suggested that the best way for Bush to make good on his pledge to become the "environmental president" was to fix the acid rain problem, and the best way to do that was by using the new tool of emissions trading. Gray liked the marketplace approach, and even before the Reagan administration expired, he put EDF staffers to work drafting legislation to make it happen. The immediate aim was to break the impasse over acid rain. But global warming had also registered as front-page news for the first time that sweltering summer of 1988; according to Krupp, EDF and the Bush White House both felt from the start that emissions trading would ultimately be the best way to address this much larger challenge.

It would be an odd alliance. Gray was a conservative multimillionaire who drove a battered Chevy modified to burn methanol. Dan Dudek, the lead strategist for EDF, was a former academic Krupp once described as either "just plain loony, or the most powerful visionary ever to apply for a job at an environmental group." But the two hit it off—a good thing, given that almost everyone else was against them.

Many Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) staffers mistrusted the new methods; they had had little success with some small-scale experiments in emissions trading, and they worried that proponents were less interested in cleaning up pollution than in doing it cheaply. Congressional subcommittee members looked skeptical when witnesses at hearings tried to explain how there could be a market for something as worthless as emissions. Nervous utility executives worried that buying allowances meant putting their confidence in a piece of paper printed by the government. At the same time, they figured that allowances might trade at $500 to $1,000 a ton, with the program costing them somewhere between $5 billion and $25 billion a year.

Environmentalists, too, were skeptical. Some saw emissions trading as a scheme for polluters to buy their way out of fixing the problem. Joe Goffman, then an EDF lawyer, recalls other environmental advocates seething when EDF argued that emissions trading was just a better solution. Other members of a group called the Clean Air Coalition tried to censure EDF for what Krupp calls "the twofold sin of having talked to the Republican White House and having advanced this heretical idea."

Misunderstandings over how emissions trading could work extended to the White House itself. When the Bush administration first proposed its wording for the legislation, the EDF and EPA staffers who had been working on the bill were shocked to see that the White House had not included a cap. Instead of limiting the amount of emissions, the bill limited only the rate of emissions, and only in the dirtiest power plants. It was "a real stomach-falling-to-the-floor moment," says Nancy Kete, who was then managing the acid rain program for the EPA. She says she realized that "we had been talking past each other for months."

EDF argued that a hard cap on emissions was the only way trading could work in the real world. It wasn't just about doing what was right for the environment; it was basic marketplace economics. Only if the cap got smaller and smaller would it turn allowances into a precious commodity, and not just paper printed by the government. No cap meant no deal, said EDF.

John Sununu, the White House chief of staff, was furious. He said the cap "was going to shut the economy down," Boyden Gray recalls. But the in-house debate "went very, very fast. We didn't have time to fool around with it." President Bush not only accepted the cap, he overruled his advisers' recommendation of an eight million-ton cut in annual acid rain emissions in favor of the ten million-ton cut advocated by environmentalists. According to William Reilly, then EPA administrator, Bush wanted to soothe Canada's bruised feelings. But others say the White House was full of sports fans, and in basketball you aren't a player unless you score in double digits. Ten million tons just sounded better.

Near the end of the intramural debate over the policy, one critical change took place. The EPA's previous experiments with emissions trading had faltered because they relied on a complicated system of permits and credits requiring frequent regulatory intervention. Sometime in the spring of 1989, a career EPA policy maker named Brian McLean proposed letting the market operate on its own. Get rid of all that bureaucratic apparatus, he suggested. Just measure emissions rigorously, with a device mounted on the back end of every power plant, and then make sure emissions numbers match up with allowances at the end of the year. It would be simple and provide unprecedented accountability. But it would also "radically disempower the regulators," says EDF's Joe Goffman, "and for McLean to come up with that idea and become a champion for it was heroic." Emissions trading became law as part of the Clean Air Act of 1990.

Oddly, the business community was the last holdout against the marketplace approach. Boyden Gray's hiking partner John Henry became a broker of emissions allowances and spent 18 months struggling to get utility executives to make the first purchase. Initially it was like a church dance, another broker observed at the time, "with the boys on one side and the girls on another. Sooner or later, somebody's going to walk into the middle." But the utility types kept fretting about the risk. Finally, Henry phoned Gray at the White House and wondered aloud if it might be possible to order the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a federally owned electricity provider, to start buying allowances to compensate for emissions from its coal-fired power plants. In May 1992, the TVA did the first deal at $250 a ton, and the market took off.

Whether cap-and-trade would curb acid rain remained in doubt until 1995, when the cap took effect. Nationwide, acid rain emissions fell by three million tons that year, well ahead of the schedule required by law. Cap-and-trade—a term that first appeared in print that year—quickly went "from being a pariah among policy makers," as an MIT analysis put it, "to being a star—everybody's favorite way to deal with pollution problems."

Almost 20 years since the signing of the Clean Air Act of 1990, the cap-and-trade system continues to let polluters figure out the least expensive way to reduce their acid rain emissions. As a result, the law costs utilities just $3 billion annually, not $25 billion, according to a recent study in the Journal of Environmental Management; by cutting acid rain in half, it also generates an estimated $122 billion a year in benefits from avoided death and illness, healthier lakes and forests, and improved visibility on the Eastern Seaboard. (Better relations with Canada? Priceless.)

No one knows whether the United States can apply the system as successfully to the much larger problem of global warming emissions, or at what cost to the economy. Following the American example with acid rain, Europe now relies on cap-and-trade to help about 10,000 large industrial plants find the most economical way of reducing their global warming emissions. If Congress approves such a system in this country—the House had approved the legislation as we went to press—it could set emissions limits on every fossil-fuel power plant and every manufacturer in the nation. Consumers might also pay more to heat and cool their homes and drive their cars—all with the goal of reducing global warming emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels over the next ten years.

But advocates argue that cap-and-trade still beats command-and-control regulation. "There's not a person in a business anywhere," says Dan Esty, an environmental policy professor at Yale University, "who gets up in the morning and says, ‘Gee, I want to race into the office to follow some regulation.' On the other hand, if you say, ‘There's an upside potential here, you're going to make money,' people do get up early and do drive hard around the possibility of finding themselves winners on this."

Richard Conniff is a 2009 Loeb Award winner for business journalism.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)