A Butterfly Species Settles in San Francisco’s Market Street

Two advocates track Western tiger swallowtails through the city and use art to encourage residents to think of the fluttering creatures as neighbors

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130828082016Red-Mural-Amber-Hasselbring-web.jpg)

“Nature is everywhere,” says lepidopterist Liam O’Brien about the tigers of San Francisco’s Market Street—Western tiger swallowtail butterflies, that is.

O’Brien and naturalist Amber Hasselbring of Art-ecology have launched a campaign called “Tigers on Market Street” to speak for the butterflies that live in the canopy of trees that line the busiest street in downtown San Francisco. They are bringing the butterfly’s story to light using science and art as the City of San Francisco re-imagines the role of this hardworking boulevard in a project called Better Market Street. On blank walls and in Powerpoint talks given to groups throughout the city, the duo display photographs, paintings and fantastical collages of the butterflies and the urban world in which they live.

One of the options being considered for Better Market Street is to make way for a Copenhagen-style bike path by removing many of the London plane trees planted 40 years ago. O’Brien and Hasselbring are all for the bike paths, but their mantra is “bikes and butterflies.”

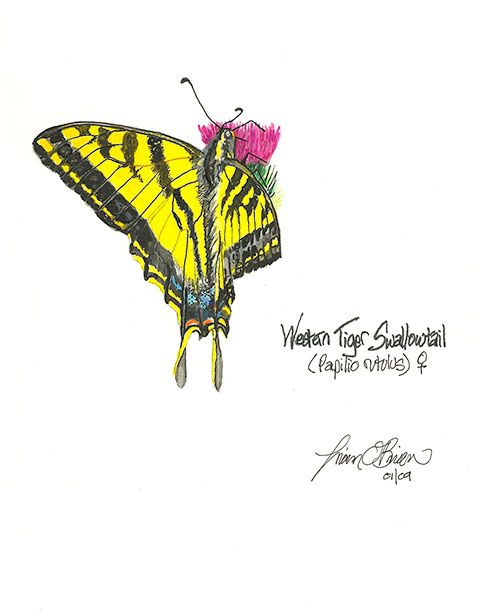

“This is not an ugly brown butterfly,” says O’Brien. “We’re talking the biggest, showiest, prettiest butterfly we have in the city.”

If you stand at the Ferry Building and look up Market Street you can see why the butterflies view the boulevard as a river canyon, their normal habitat. Naturalist John Muir also referred to city streets as canyons—he said he was more comfortable picking through an ice field than to be in the “terrible canyons of New York.” But to a butterfly, San Francisco’s city canyons provide a kind of haven.

Some species of butterflies need hillside habitats, but a tiger swallowtail lives in corridors on the banks of waterways. “Market Street is a tree-lined linear concourse that our species calls a street,” says O’Brien. “Through the point-of-view of the creature this is a river.”

To understand how a street becomes a river to these creatures, you have to slip into that point of view, says O’Brien. It’s not the species of tree that attracts them as much as it is the topographical lay. They patrol long linear things with plantings on both sides. “It’s a random accident that this street looks just like a river,” he says, “which is the magic of this story.”

They are also attracted to glades, which, in San Francisco, means open areas downtown that are protected by an initiative approved by voters in 1984 that controls shadows from tall buildings. The glades and nearby parks provide sunlight, water from fountains or sprinklers, nectar sources and an increased chance of finding a mate.

O’Brien and Hasselbring received a grant to conduct a six-month survey of the butterflies. This summer they have walked transects from the Civic Center to the Ferry Building to count them, observe their life cycles and note their nectar and larval sources. Thirteen is the highest number they have counted on any given transect, but that number is deceiving given that a butterfly has four stages of life: egg, larvae, pupae and sexually mature adult, or imago.

We spot our third butterfly after ten minutes of walking on a sunny August day. O’Brien explains that a butterfly has an 80 percent chance of being eaten in each of its four stages, which makes the one in front of us seem like a miracle. It lands on a leaf close enough for us to see the yellow and black stripes running the length of its extremely furry body, which explain the “tiger” in the butterfly’s name.

Hasselbring and O’Brien photograph each butterfly they see, then geo-tag the picture and post it on iNaturalist, an app to record and share observations in nature. They also use the images in artwork to help communicate the tiger’s story.

O’Brien, who describes himself as an Old World illustrator, has not always been a lepidopterist. His metamorphosis happened 15 years ago when a Western tiger swallowtail, the poster child of this very campaign, floated into his backyard and changed his life. To explain why he left a successful acting career to become San Francisco’s butterfly expert, he quoted Russian novelist and lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov: “When I’m in a rarefied land with a rare butterfly and its host plant all that I love rushes in like a momentary vacuum and I am at one.”

Hasselbring paints and engages in performance art. She moved to San Francisco ten years ago from Colorado and jumped into the natural side of San Francisco. Now she is the director of Nature in the City, a nonprofit that advocates for ecological restoration and stewardship in San Francisco, and sees art in the everyday. She considers all of it art—from watching the butterfly’s behavior to talking to people on the street to installing a temporary mural at Seventh and Market, which she did in 2011.

“We’re not butterfly huggers,” says O’Brien. “We just want to celebrate what’s already here. If a landscape architect had been paid to create swallowtail habitat on Market Street they couldn’t have done a better job.”

O’Brien and Hasselbring want the butterflies to be a part of an improved Market Street. They’d like to see more hardwood trees and planter boxes with butterfly-friendly flowers that will bring the butterflies down from the canopy where people can see them. They’d also like to design standalone signs similar to those in Paris that celebrate natural biodiversity in that city. On one side, the signs would illustrate the life cycle of the tiger swallowtails, and on the other side, they would list and illustrate all the other creatures in the downtown area.

“I’d like to give people in the densest downtown area these nature moments,” says Hasselbring. “With all the richness that we have on our hilltops and in our city, we could become the city of biodiversity.”

The Western tiger swallowtails of Market Street have ambassador potential. The showy species offers an opportunity to connect a lot of people with nature, and help them to see that nature can be celebrated everywhere, even in the canyons of San Francisco.