A Crude Awakening in the Gulf of Mexico

Scientists are just beginning to grasp how profoundly oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill has devastated the region

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Oil-workboat-near-site-of-Deepwater-Horizon-platform-631.jpg)

Life seems almost normal along the highway that runs the length of Grand Isle, a narrow curl of land near the toe of Louisiana’s tattered boot. Customers line up for snow cones and po’ boys, graceful live oaks stand along the island’s central ridge, and sea breezes blow in from the Gulf of Mexico. But there are few tourists here this summer. The island is filled with cleanup crews and locals bracing for the next wave of anguish to wash ashore from the crippled well 100 miles to the southeast.

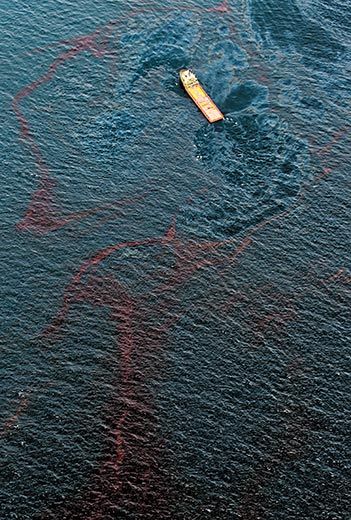

Behind Grand Isle, in the enormous patchwork of water and salt marsh called Barataria Bay, tar balls as big as manhole covers float at the surface. Oily sheens, some hundreds of yards across, glow dully on the water. Below a crumbling brick fort built in the 1840s, the marsh edges are smeared with thick brown gunk. A pair of dolphins break the water’s surface, and a single egret walks along the shore, its wings mottled with crude. Inside the bay, the small islands that serve as rookeries for pelicans, roseate spoonbills and other birds have suffered waves of oil, and many of the mangroves at the edges have already died. Oil is expected to keep washing into the bay for months.

Even here, at the heart of the disaster, it’s hard to fathom the reach of the spill. Oil is penetrating the Gulf Coast in countless ways—some obvious, some not—and could disrupt habitats and the delicate ecology for years to come. For the scientists who have spent decades trying to understand the complexities of this natural world, the spill is not only heartbreaking, but also deeply disorienting. They are just beginning to study—and attempting to repair—a coast transformed by oil.

About a hundred miles inland from Grand Isle, on the shady Baton Rouge campus of Louisiana State University, Jim Cowan and a dozen of his laboratory members gather to discuss their next move. In the agonizing days since the spill began, Cowan’s fisheries lab has become something of a command center, with Cowan guiding his students in documenting the damage.

Cowan grew up in southern Florida and has a particular affection for the flora, fauna and people of the lush wetlands of southern Louisiana; he’s studied Gulf ecosystems from inland marshes to offshore reefs. Much of his research has focused on fish and their habitats. But now he worries that the Gulf he’s known for all these years is gone. “These kids are young, and I don’t think they realize yet how it’s going to change their lives,” he says of the oil. “The notion of doing basic science, basic ecology, where we’re really trying to get at the drivers of the ecosystem...” He pauses and shakes his head. “It’s going to be a long time before we get oil out of the equation.”

Cowan knows all too well that the Deepwater Horizon spill is only the latest in an almost operatic series of environmental disasters in southern Louisiana. The muddy Mississippi River used to range over the entire toe of Louisiana, building land with its abundant sediment. As people constructed levees to keep the river in place, the state began to lose land. The marshy delta soil continued to compact and sink below the water, as it had for millennia, but not enough river sediments arrived to replace it. Canals built by the oil and gas industry sped soil erosion, and violent storms blasted away exposed fragments of marshland. Meanwhile, as the flow of river water changed, the Gulf of Mexico began to intrude inland, turning freshwater wetlands into salt marshes.

Today, southern Louisiana loses about a football field’s worth of land each and every half-hour. Pavement ends abruptly in water, bayous reach toward roadsides, and mossy crypts tumble into bays. Nautical maps go out of date in a couple of years, and boat GPS screens often show watercraft seeming to navigate over land. Every lost acre means less habitat for wildlife and weaker storm protection for humans.

But for Cowan and many other scientists who study the Gulf, the oil spill is fundamentally different. Though humans have dramatically accelerated Louisiana’s wetlands loss, soil erosion and seawater intrusion, these are still natural phenomena, a part of the workings of any river delta. “The spill is completely foreign,” Cowan says. “We’re adding a toxic chemical to a natural system.”

One of the largest shrimp docks in North America, a jumble of marinas, warehouses, nets and masts, stands on the bay side of Grand Isle. In the wake of the spill, many shrimp boats are docked, and those on the open water are fitted not with nets but with loops of oil-skimming orange boom. The shrimp processing sheds, usually noisy with conveyor belts and rattling ice and voices sharing gossip and jokes, are silent.

One lone boat is trawling Barataria Bay, but it’s not netting dinner. Kim de Mutsert and Joris van der Ham, postdoctoral researchers in Cowan’s lab, are sampling fish and shrimp from both clean and oiled marshlands. The Dutch researchers are known for their tolerance of rough water. “Kim, she’s fearless,” says Cowan. “Man, she scares me sometimes.”

The outer bands of a hurricane are beginning to whip the water with wind and drizzle, but De Mutsert and Van der Ham steer their 20-foot motorboat into the bay. Calling instructions to each other in Dutch, they soon arrive at a small island of cordgrass and mangroves, one of their lightly oiled study sites.

At their first sampling point, in shallow, bathtub-warm water near the island, Van der Ham stands at the back of the boat, gripping the metal-edged planks at the mouth of a long, skinny net. It’s a kind of trawl used by many commercial shrimpers. “Except their nets are a lot bigger, and they’re a lot better at using them,” says Van der Ham as he untangles some wayward ropes.

After ten minutes of trawling, De Mutsert and Van der Ham muscle up the net, which is twitching with dozens of small, silvery fish—menhaden, croaker and spot. A few shrimp—some juveniles with jellylike bodies, some adults nearly eight inches long—intermingle with the fish. All of these species depend on marshlands for survival: they spawn at sea, and the juvenile fish and shrimp ride the tides into Barataria and other bays, using the estuaries as nurseries until they grow to adulthood.

When De Mutsert returns to the lab in Baton Rouge, she’ll debone her catches—“I’m really good at filleting very tiny fish,” she says, laughing—and analyze their tissue, over time building a detailed picture of the sea life’s growth rates, overall health, food sources and the amount of oil compounds in their bodies.

The fish and shrimp are members of an enormously complex food web that spans the Louisiana coast from inland freshwater swamps to the edge of the continental shelf and beyond. Freshwater plants, as they die and float downstream, supply nutrients; fish and shrimp that grow to adulthood in the marshes return to sea to spawn on the continental shelf; larger fish like grouper and red snapper, which spend their lives at sea, use coral reefs to forage and spawn. Even the Mississippi River, constrained as it is, provides spawning habitat for tuna where its water meets the sea.

Unlike the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska, in which a tanker dumped oil on the surface of the water, the BP oil gushed from the seafloor. Partly because of BP’s use of dispersants at the wellhead, much of the oil is suspended underwater, only slowly making its way to the surface. Some scientists estimate that 80 percent is still underwater—where it can smother sponges and corals, interfere with many species’ growth and reproduction, and do long-term damage to wildlife and habitats.

“The oil is coming into the food web at every point,” says Cowan. “Everything is affected, directly and indirectly, and the indirect effects may be the more troubling ones, because they’re so much harder to understand.” Data from De Mutsert and others in the lab will illuminate where the food web is most stressed and suggest ways to protect and repair it.

As penetrating rain descends, De Mutsert and Van der Ham matter-of-factly don rain jackets and keep trawling, stopping just before sunset. Their samples secured, they finally make a break for shore, slamming over the growing whitecaps in the failing light, then maneuvering around tangles of floating, oil-soaked boom. Drenched to the skin, they pull into the dock.

“Yeah,” De Mutsert acknowledges nonchalantly. “That was a little crazy.”

But tomorrow, hurricane notwithstanding, they’ll do it all again.

Jim Cowan’s friend and colleague Ralph Portier paces impatiently along the edge of Barataria Bay, on the inland shore of Grand Isle. He is a boyish-faced man whose rounded initial t’s give away his Cajun heritage. “I want to get to work so bad,” he says.

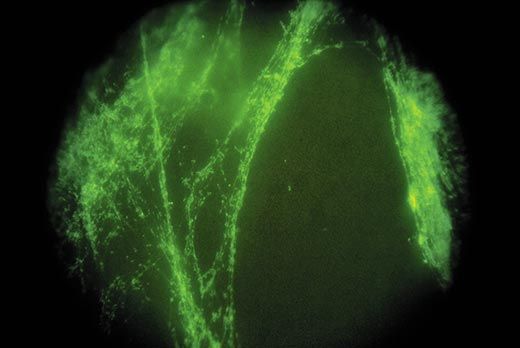

Portier, an environmental biologist at Louisiana State, specializes in bioremediation—the use of specialized bacteria, fungi and plants to digest toxic waste. Bioremediation gets little public attention, and fiddling with the ecosystem does carry risks, but the technique has been used for decades, quietly and often effectively, to help clean up society’s most stubborn messes. Portier has used bioremediation on sites ranging from a former mothball factory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to a 2006 Citgo spill near Lake Charles, Louisiana, in which two million gallons of waste oil flowed into a nearby river and bayou following a violent storm. He has collected promising organisms from all over the world, and labels on the samples of microorganisms in his lab freezers and refrigerators betray a litany of disasters. “Name a Superfund site, and it’s in there,” he says.

All but the most toxic of toxic waste sites have their own naturally occurring suite of microorganisms, busily chewing away at whatever was spilled, dumped or abandoned. Sometimes Portier simply encourages these existing organisms by adding the appropriate fertilizers; other times he adds bacterial reinforcements.

Portier points out that other oil-spill cleanup techniques—booms, shovels, skimmers, even paper towels—may make a site look better but leave a toxic residue. The rest of the job is usually accomplished by oil-eating bacteria (which are already at work on the BP spill) digesting the stuff in marshes and at sea. Even in a warm climate like the Gulf coast, the “bugs,” as Portier calls them, can’t eat fast enough to save the marsh grasses—or the entire web of other plants and animals affected by the spill. But he thinks his bugs could speed the natural degradation process and make the difference between recovery and disappearance for a great deal of oily marshland. Desperate to give it a try, he is waiting for permits to test his technique. He says his biological reactors, large black plastic tanks sitting idle at the water’s edge, could make some 30,000 gallons of bacterial solution a day—enough to treat more than 20 acres—at a cost of about 50 cents a gallon. “I really think I could help clean this thing up,” he says.

Like Cowan, Portier worries about the three-dimensional nature of the BP spill. As the millions of gallons of oil from the broken well slowly rises to the surface in coming months, it will wash ashore again and again, creating, in effect, recurrent spills on the beaches and marshlands. “Here, the legacy is in the ocean, not on the beach,” Portier says. “This spill is going to give us different kinds of challenges for years to come.”

Yet Portier is more optimistic than Cowan. If he can employ his bugs on the Louisiana coast, he says, salt marsh and other wetland habitat could start recovering in a matter of months. “My ideal scenario for next spring is that we fly over the bayous of Barataria and see this huge green band of vegetation coming back,” he says.

Portier has a personal stake in the spill. He was raised just west of Barataria Bay. He and his eight siblings have four PhDs and a dozen master’s degrees among them. They now live all over the Southeast but return to Bayou Petit Caillou several times a year. Oil has already appeared at the mouth of his home bayou.

When Portier was growing up, he remembers, hurricanes were a part of life. If a storm threatened, his entire family—uncles, aunts, cousins, grandparents—would squeeze into his parents’ house, which sat on relatively high ground. As the storm roared over them, his relatives would telephone their homes down the bayou. If the call went through, they knew their house was still there. If they got a busy signal, that meant a problem.

Today, what Portier hears in the marshes—or doesn’t hear—is worse than a busy signal. “It’s the new Silent Spring in there,” he says. “You usually hear birds singing, crickets chirping, a whole cacophony of sound. Now, you hear yourself paddling, and that’s it.”

He hopes it won’t be long before the marshes once again pulse with chirps, croaks and screeches. “When I hear crickets and birds again in those marshes, that’s how I’ll know,” he says. “That’s how I’ll know the phone is ringing.”

Michelle Nijhuis has written about puffins, Walden Pond and the Cahaba River for Smithsonian. Matt Slaby is a photographer based in Denver.