A Plague of Pigs in Texas

Now numbering in the millions, these shockingly destructive and invasive wild hogs wreak havoc across the southern United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/wild-hogs-running-631.jpg)

About 50 miles east of Waco, Texas, a 70-acre field is cratered with holes up to five feet wide and three feet deep. The roots below a huge oak tree shading a creek have been dug out and exposed. Grass has been trampled into paths. Where the grass has been stripped, saplings crowd out the pecan trees that provide food for deer, opossums and other wildlife. A farmer wanting to cut his hay could barely run a tractor through here. There’s no mistaking what has happened—this field has gone to the hogs.

“I’ve trapped 61 of ‘em down here in the last month,” says Tom Quaca, whose in-laws have owned this land for about a century. “But at least we got some hay out of here this year. First time in six years.” Quaca hopes to flatten the earth and crush the saplings with a bulldozer. Then maybe—maybe—the hogs will move onto adjacent hunting grounds and he can once again use his family’s land.

Wild hogs are among the most destructive invasive species in the United States today. Two million to six million of the animals are wreaking havoc in at least 39 states and four Canadian provinces; half are in Texas, where they do some $400 million in damages annually. They tear up recreational areas, occasionally even terrorizing tourists in state and national parks, and squeeze out other wildlife.

Texas allows hunters to kill wild hogs year-round without limits or capture them alive to take to slaughterhouses to be processed and sold to restaurants as exotic meat. Thousands more are shot from helicopters. The goal is not eradication, which few believe possible, but control.

The wily hogs seem to thrive in almost any conditions, climate or ecosystem in the state—the Pineywoods of east Texas; the southern and western brush country; the lush, rolling central Hill Country. They are surprisingly intelligent mammals and evade the best efforts to trap or kill them (and those that have been unsuccessfully hunted are even smarter). They have no natural predators, and there are no legal poisons to use against them. Sows begin breeding at 6 to 8 months of age and have two litters of four to eight piglets—a dozen is not unheard of—every 12 to 15 months during a life span of 4 to 8 years. Even porcine populations reduced by 70 percent return to full strength within two or three years.

Wild hogs are “opportunistic omnivores,” meaning they’ll eat most anything. Using their extra-long snouts, flattened and strengthened on the end by a plate of cartilage, they can root as deep as three feet. They’ll devour or destroy whole fields—of sorghum, rice, wheat, soybeans, potatoes, melons and other fruits, nuts, grass and hay. Farmers planting corn have discovered that the hogs go methodically down the rows during the night, extracting seeds one by one.

Hogs erode the soil and muddy streams and other water sources, possibly causing fish kills. They disrupt native vegetation and make it easier for invasive plants to take hold. The hogs claim any food set out for livestock, and occasionally eat the livestock as well, especially lambs, kids and calves. They also eat such wildlife as deer and quail and feast on the eggs of endangered sea turtles.

Because of their susceptibility to parasites and infections, wild hogs are potential carriers of disease. Swine brucellosis and pseudorabies are the most problematic because of the ease with which they can be transmitted to domestic pigs and the threat they pose to the pork industry.

And those are just the problems wild hogs cause in rural areas. In suburban and even urban parts of Texas, they’re making themselves at home in parks, on golf courses and on athletic fields. They treat lawns and gardens like a salad bar and tangle with household pets.

Hogs, wild or otherwise, are not native to the United States. Christopher Columbus introduced them to the Caribbean, and Hernando De Soto brought them to Florida. Texas’ early settlers let pigs roam free until needed; some were never recovered. During wars or economic downturns, many settlers abandoned their homesteads and the pigs were left to fend for themselves. In the 1930s, Eurasian wild boars were brought to Texas and released for hunting. They bred with free-ranging domestic animals and escapees that had adapted to the wild.

And yet wild hogs were barely more than a curiosity in the Lone Star State until the 1980s. It’s only since then that the population has exploded, and not entirely because of the animals’ intelligence, adaptability and fertility. Hunters found them challenging prey, so wild hog populations were nurtured on ranches that sold hunting leases; some captured hogs were released in other parts of the state. Game ranchers set out feed to attract deer, but wild hogs pilfered it, growing more fecund. Finally, improved animal husbandry reduced disease among domestic pigs, thereby reducing the incidence among wild hogs.

Few purebred Eurasian wild boars are left today, but they have hybridized with feral domestic hogs and continue to spread. All are interchangeably called wild or feral hogs, pigs or boars; in this context, “boar” can refer to a male or female. (Technically, “feral” refers to animals that can be traced back to escaped domestic pigs, while the more all-encompassing “wild” refers to any non-domestic animals.) Escaped domestic hogs adapt to the wild in just months, and within a couple of generations they transform into scary-looking beasts as mean as can be.

The difference between domestic and wild hogs is a matter of genetics, experience and environment. The animals are “plastic in their physical and behavioral makeup,” says wild hog expert John Mayer of the Savannah River National Laboratory in South Carolina. Most domestic pigs have sparse coats, but descendants of escapees grow thick bristly hair in cold environments. Dark-skinned pigs are more likely than pale ones to survive in the wild and pass along their genes. Wild hogs develop curved “tusks” as long as seven inches that are actually teeth (which are cut from domestics when they’re born). The two teeth on top are called whetters or grinders, and the two on the bottom are called cutters; continual grinding keeps the latter deadly sharp. Males that reach sexual maturity develop “shields” of dense tissue on their shoulders that grow harder and thicker (up to two inches) with age; these protect them during fights.

Wild hogs are rarely as big as pen-bound domestics; they average 150 to 200 pounds as adults, although a few reach more than 400 pounds. Well-fed pigs develop large, wide skulls; those with a limited diet, as in the wild, grow smaller, narrower skulls with longer snouts useful for rooting. Wild pigs have poor eyesight but good hearing and an acute sense of smell; they can detect odors up to seven miles away or 25 feet underground. They can run 30 miles an hour in bursts.

Adult males are solitary, keeping to themselves except when they breed or feed from a common source. Females travel in groups, called sounders, usually of 2 to 20 but up to 50 individuals, including one or more sows, their piglets and maybe a few adoptees. Since the only thing (besides food) they cannot do without is water, they make their homes in bottomlands near rivers, creeks, lakes or ponds. They prefer areas of dense vegetation where they can hide and find shade. Because they have no sweat glands, they wallow in mudholes during the hot months; this not only cools them off but also coats them with mud that keeps insects and the worst of the sun’s rays off their bodies. They are mostly nocturnal, one more reason they’re difficult to hunt.

“Look up there,” exclaims Brad Porter, a natural resource specialist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, as he points up a dirt road cutting across Cow Creek Ranch in south Texas. “That’s hog-hunting 101 right there.” As he speaks, his hunting partner’s three dogs, who’d been trotting alongside Porter’s pickup truck, streak through the twilight toward seven or eight wild hogs breaking for the brush. Porter stops to let his own two dogs out of their pens in the bed of the pickup and they, too, are off in a flash. When the truck reaches the area where the pigs had been, Porter, his partner Andy Garcia and I hear frantic barking and a low-pitched sighing sound. Running into the brush, we find the dogs have surrounded a red and black wild hog in a clearing. Two dogs have clamped onto its ears. Porter jabs his knife just behind the hog’s shoulder, dispatching it instantly. The dogs back off and quiet down as he grabs its rear legs and drags it back to his truck.

“He’s gonna make good eatin’,” Garcia says of the dead animal, which weighs about 40 pounds.

The 3,000-acre ranch, in McMullen County, has been in the family of Lloyd Stewart’s wife, Susan, since the mid-1900s. Stewart and his hunting and wildlife manager, Craig Oakes, began noticing wild hogs on the land in the 1980s, and the animals have become more of a problem every year. In 2002, Stewart began selling hog-hunting leases, charging $150 to $200 for a daylong hunt and $300 for weekends. But wild hogs have become so common around the state that it’s getting hard to attract hunters. “Deer hunters tell us they have a lot of hogs at home,” Oakes says, “so they don’t want to pay to come shoot them here.” The exception is trophy boars, defined as any wild pig with tusks longer than three inches. These bring around $700 for a weekend hunt.

“Most of the hogs that are killed here are killed by hunters, people who will eat them,” Stewart says. He’ll fly over the ranch to try to count the hogs, but unlike some landowners who are overrun, he has yet to shoot them from the air. “We’re not that mad at ‘em yet,” Oakes chuckles. “I hate to kill something and not use it.”

Many hunters prefer working with dogs. Two types of dogs are used in the hunt. Bay dogs—usually curs such as the Rhodesian Ridgeback, black-mouth cur or Catahoula or scent hounds such as the foxhound or Plott Hound—sniff out and pursue the animals. A hog will attempt to flee, but if cornered or wounded will likely attack, battering the bay dogs with its snout or goring them with its tusks. (Some hunters outfit their dogs in Kevlar vests.) But if the dog gets right up in the hog’s face while barking sharply, it can hold the hog “at bay.” Once the bay dogs spring into action, catch dogs—typically bulldogs or pit bulls—are released. Catch dogs grab the bayed pig, usually at the base of the ear, and wrestle it to the ground, holding it until the hunter arrives to finish it off.

Dogs show off their wild-hog skills at bayings, also known as bay trials, which are held most weekends in rural towns across Texas. A wild hog is released in a large pen and one or two dogs attempt to bay it, while spectators cheer. Trophies are awarded in numerous categories; gambling takes the form of paying to “sponsor” a particular dog and then splitting the pot with cosponsors if it wins. Occasionally bayings serve as fund-raisers for community members in need.

Ervin Callaway holds a baying on the third weekend of every month. His pen is down a rutted dirt road off U.S. Route 59 between the east Texas towns of Lufkin and Nacogdoches, and he’s been doing this for 12 years. His son Mike is one of the judges.

“Here’s how it works,” Mike says as a redheaded preteenager preps a red dog. “The dog has two minutes in the pen with a hog and starts with a perfect score of 10. We count off any distractions, a tenth of a point for each. If a dog controls the hog completely with his herding instincts, and stares him down, it’s a perfect bay. If a dog catches a pig, it’s disqualified—we don’t want any of our dogs or hogs tore up.”

“Hog out,” someone shouts, and a black and white hog (its tusks removed) emerges from a chute as two barking dogs are released to charge it. When it tries to move away, a young man uses a plywood shield to funnel it toward the dogs. They stop less than a foot away from the hog and make eye contact, barking until the animal shoots between them toward the other side of the pen. As the dogs close back in, the hog swerves hard into a fence, then bounces off. The smaller dog grabs its tail but is spun around until it lets go. The pig runs into a wallow and sits there. The yellow dog bays and barks, but from maybe three feet away, too far to be effective, and then it loses concentration and backs off. The pig exits through the chute. Neither dog scores well.

Several states, including Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina and North Carolina, have outlawed bayings in response to protests from animal rights groups. Louisiana bars them except for Uncle Earl’s Hog Dog Trials in Winnfield, the nation’s largest. That five-day event began in 1995 and draws about 10,000 people annually. (The 2010 event was canceled because of disputes among the organizers.)

But bayings continue to take place on a smaller scale elsewhere, as do bloodier hog-catch trials in which dogs attack penned-in wild hogs and wrestle them to the ground. The legality of both events is in dispute, but local authorities tend not to prosecute. “The law in Texas is that it’s illegal for a person to cause one animal to fight another previously wild animal that has been captured,” says Stephan Otto, director of legislative affairs and staff attorney for the Animal Legal Defense Fund, a national group based in northern California. “But the legal definition of words like ‘captured’ and ‘fight’ has never been established. A local prosecutor would have to argue these things, and so far nobody has.”

Brian “Pig Man” Quaca (Tom Quaca’s son) paces the floor of his hunting lodge, waving his arms and free-associating about hogs he has known. There’s the one that rammed his pickup truck; the bluish hog with record-length tusks that he bagged in New Zealand; and the “big ‘un” he blew clean off its feet with a rifle only to see the beast get up and run away. “They’re just so smart, that’s why I love them,” he says. “You can fool deer 50 percent of the time, but hogs’ll win 90 percent of the time.”

Quaca, 38, began rifle hunting when he was 4 years old but switched to bowhunting at age 11. He likes the silence after the shot. “It’s just more primitive to use a bow, way more exciting,” he says. As a teen, he eagerly helped neighbors clear out unwanted hogs. Now he guides hunts at Triple Q Outfitters, a fenced-in section of the property his wife’s family owns. A customer dubbed him Pig Man, and it stuck. His reputation grew with the launch last year of “Pig Man, the Series,” a Sportsman Channel TV program for which he travels the globe hunting wild hogs and other exotic animals.

About an hour before sunset, Quaca takes me to a blind near a feeding station in the woods. Just as he’s getting his high-powered bow ready, a buck walks into the clearing and begins eating corn; two more are close behind. “The deer will come early to get as much food as they can before the pigs,” he says. “It’s getting close to prime time now.”

A slight breeze eases through the blind. “That’s gonna let those pigs smell us now. They probably won’t come near.” He rubs an odor-neutralizing cream into his skin and hands me the tube. The feeding station is at least 50 yards away, and it’s hard to believe our scents can carry that far, let alone that there’s a nose sharp enough to smell them. But as it gets darker, there are still no hogs.

“It sounds like a hog might be over around those trees,” Pig Man whispers, pointing to our left. “It sounded like he popped his teeth once or twice. I can promise you there’s pigs close by, even if they don’t show themselves. Those deer will stay however long they can and never notice us. But the pigs are smart.”

The darkness grows, and Quaca starts packing to leave. “They won again,” he says with a sigh. I tell him I still can’t believe such a mild breeze carried our scents all the way to the feed. “That’s why I like pigs so much,” Quaca replies. “If the slightest thing is wrong—any tiny little thing—they’ll get you every time. The sumbitches will get you every time.”

The next morning, Tom shows me some flash photographs of the feeding station taken by a sensor camera about a half-hour after we left. In the pictures, a dozen feral pigs of all sizes are chowing down on corn.

To be sold commercially as meat, wild hogs must be taken alive to one of nearly 100 statewide buying stations. One approved technique for capturing hogs is snaring them with a noose-like device hanging from a fence or tree; because other wildlife can get captured, the method has fewer advocates than trapping, the other approved technique. Trappers bait a cage with food meant to attract wild hogs but not other animals (fermented corn, for example). The trapdoor is left open for several days, until the hogs are comfortable with it. Then it’s rigged to close on them. Trapped pigs are then taken to a buying station and from there to a processing plant overseen by U.S. Department of Agriculture inspectors. According to Billy Higginbotham, a wildlife and fisheries specialist with the Texas AgriLife Extension Service, 461,000 Texas wild hogs were processed between 2004 and 2009. Most of that meat ends up in Europe and Southeast Asia, where wild boar is considered a delicacy, but the American market is growing, too, though slowly.

Wild hog is neither gamy nor greasy, but it doesn’t taste like domestic pork, either. It’s a bit sweeter, with a hint of nuttiness, and is noticeably leaner and firmer. Boasting one-third less fat, it has fewer calories and less cholesterol than domestic pork. At the LaSalle County Fair and Wild Hog Cook-Off held each March in Cotulla, 60 miles northeast of the Mexican border, last year’s winning entry in the exotic category was wild hog egg rolls—pulled pork and chopped bell peppers encased in a wonton. But there were far more entries in the barbecue division; this is Texas, after all.

“There’s not much secret to it,” insists Gary Hillje, whose team won the 2010 barbecue division. “Get a young female pig—males have too strong a flavor—50 or 60 pounds, before she’s had a litter, before she’s 6 months old. Check to make sure it’s healthy; it should be shiny and you can’t see the ribs. Then you put the hot coals under it and cook it low and slow.”

The LaSalle County Fair also includes wild hog events in its rodeo. Five-man teams from eight local ranches compete in tests of cowboy skills, though cowboys are rarely required to rope and tie hogs in the wild. “But we might chase one down, rope it and put it in a cage to fatten it a couple months for a meal,” says a grinning Jesse Avila, captain of the winning 2010 La Calia Cattle Company Ranch team.

As the wild hog population continues to grow, Texas’ love-hate relationship with the beasts veers toward hate. Michael Bodenchuk, director of the Texas Wildlife Services Program, notes that in 2009 the state killed 24,648 wild hogs, nearly half of them from the air (a technique most effective in areas where trees and brush provide little cover). “But that doesn’t really affect the total population much,” he adds. “We go into specific areas where they’ve gotten out of control and try to bring that local population down to where the landowners can hopefully maintain it.”

In the past five years Texas AgriLife Extension has sponsored some 100 programs teaching landowners and others how to identify and control wild hog infestations. “If you don’t know how to outsmart these pigs, you’re just further educating them,” says Higginbotham, who points to a two-year program that reduced the economic impact of wild hogs in several regions by 66 percent. “Can we hope to eradicate feral hogs with the resources we have now? Absolutely not,” he says. “But we’re much further along than we were five years ago; we have some good research being done and we’re moving in the right direction.”

For example, Duane Kraemer, a professor of veterinary physiology and pharmacology at Texas A&M University, and his team have discovered a promising birth control compound. Now all they have to do is figure out a way to get wild hogs, and only wild hogs, to ingest it. “Nobody believes that can be done,” he says. Tyler Campbell, a wildlife biologist with the USDA’s National Wildlife Research Center at Texas A&M-Kingsville, and Justin Foster, a research coordinator for Texas Parks and Wildlife, are confident there must be a workable poison to kill wild hogs—though, once again, the delivery system is the more vexing issue. Campbell says the use of poison is at least five to ten years away.

Until then, there’s a saying common to hunters and academics, landowners and government officials—just about anyone in the Southwest: “There’s two kinds of people: those that have wild pigs and those that will have wild pigs.”

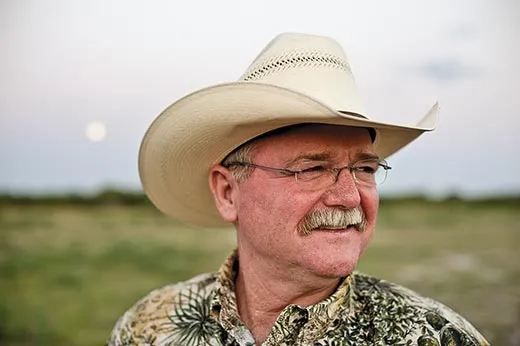

John Morthland writes about the food, music and regional culture of Texas and the South. He lives in Austin. Photographer Wyatt McSpadden also lives in Austin.