North America’s Earliest Smokers May Have Helped Launch the Agricultural Revolution

As archaeologists push back the dates for the spread of tobacco use, new questions are emerging about trade networks and agriculture

:focal(860x502:861x503)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/79/9b798e23-db10-4f51-a388-4bdd09adf94a/https___collectionsnmnhsiedu_media__irn11098267.jpg)

In the beginning, there was smoke. It snaked out of the Andes from the burning leaves of Nicotiana tabacum some 6,000 years ago, spreading across the lands that would come to be known as South America and the Caribbean, until finally reaching the eastern shores of North America. It intermingled with wisps from other plants: kinnickinnick and Datura and passionflower. At first, it meant ceremony. Later, it meant profit. But always the importance of the smoke remained.

Today, archaeologists aren’t just asking which people smoked the pipes and burned the tobacco and carried the seeds from one continent to the next; they’re also considering how smoking reshaped our world.

“We teach in history and geology classes that the origins of agriculture led to the making of the modern world,” says anthropologist Stephen Carmody of Troy University. “The one question that keeps popping up is which types of plants were domesticated first? Plants that would’ve been important for ritual purposes, or plants for food?”

To answer that question and others, Carmody and his colleagues have turned to archaeological sites and old museum collections. They scrape blackened fragments from 3,000-year-old pipes, collect plaque from the teeth of the long-dead, and analyze biomarkers clinging to ancient hairs. With new techniques producing ever more evidence, a clearer picture is slowly emerging from the hazy past.

* * *

That the act of smoking is even possible might be a matter of our unique evolution. A 2016 study found that a genetic mutation appearing in humans, but not in Neanderthals, provided us with the unique ability to tolerate the carcinogenic matter of campfires and burnt meat. It’s an ability we’ve been exploiting for millennia, from smoking marijuana in the Middle East to tobacco in the Americas.

For Carmody, the quest to unravel the mysteries of American smoke started with pollen. While still completing his graduate studies, he wanted to know whether traces of smoking plants could be identified from the microscopic remnants of pollen left behind in smoking implements like pipes and bowls (though he ultimately found other biomarkers to be more useful than pollen spores). He started growing traditional crops to learn as much as possible about their life cycles—including tobacco.

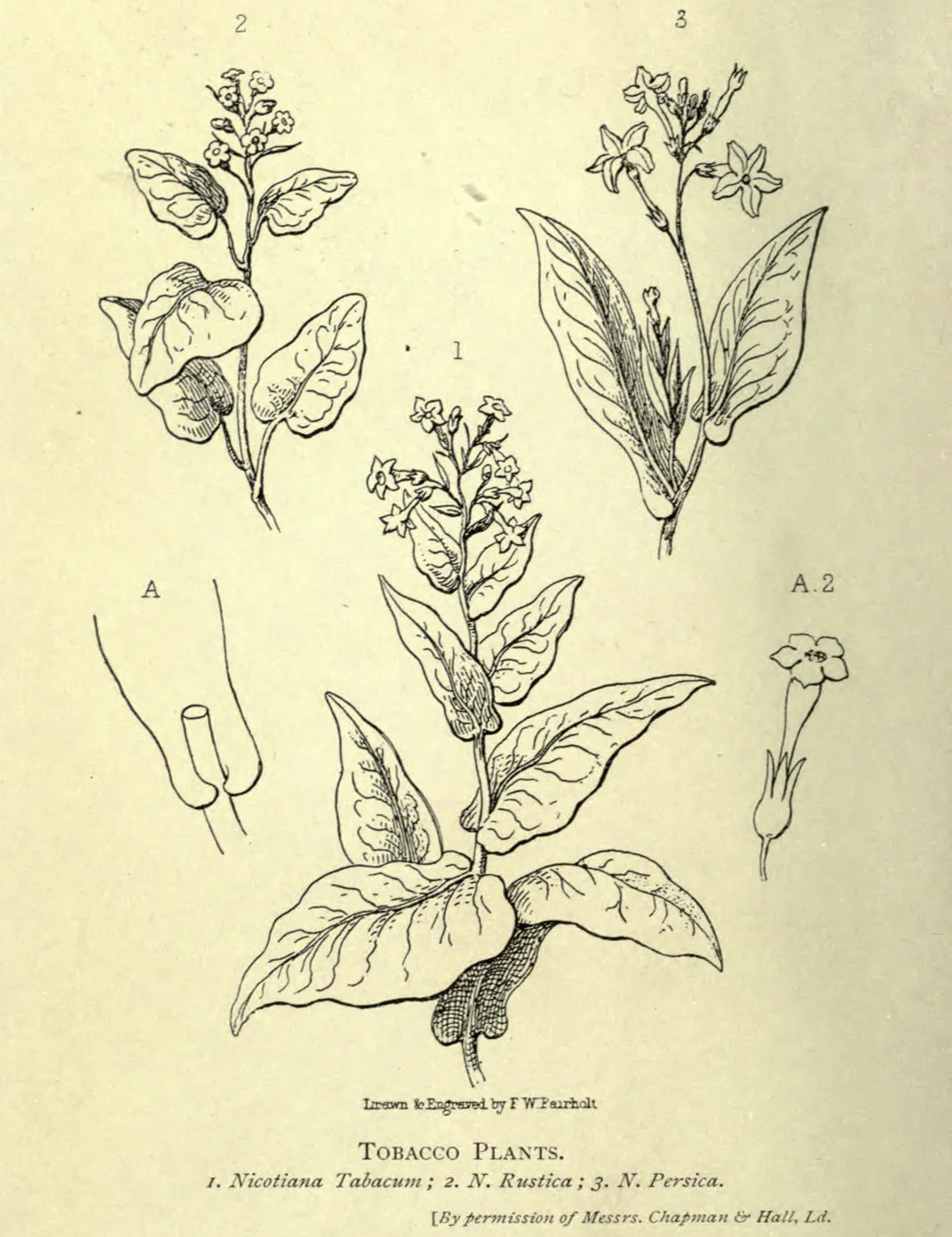

Of all the domesticated plants found across the Americas, tobacco holds a special role. Its chemical properties sharpen the mind, provide a boost of energy, and can even cause visions and hallucinations in large doses. It’s uses among Native American groups have been complex and varied, changing over time and from one community to the next. Though indigenous groups historically used over 100 plants for smoking, different strains of tobacco were actually cultivated, including Nicotiana rustica and Nicotiana tabacum, both of which contained higher quantities of nicotine. But it’s still unclear when exactly that happened, and how those two species spread from South America to North America.

This summer, Carmody and his colleagues published a paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports that unequivocally extended the reign of tobacco in North America. Prior to their find, the oldest evidence for tobacco smoking on the continent came from a smoking tube dated to 300 BC. By examining a number of smoking implements excavated from the Moundville complex in central Alabama, they uncovered traces of nicotine in a pipe from around 1685 BC. The find is the earliest evidence of tobacco ever found in North America—though Carmody says there are probably even older pipes out there.

The new date pushes tobacco even closer to the time when indigenous people were beginning to domesticate crops. Could tobacco have launched the agricultural revolution in North America? It’s still too early to say, but Carmody definitely thinks it’s worth considering why people who had successfully lived as hunter-gatherers might have made the transition to planting gardens and nurturing crops.

Shannon Tushingham, an anthropologist at Washington State University, has been asking the same question—only she’s looked at the Pacific Northwest, a colder, wetter environment where different species of tobacco grow: Nicotiana quadrivalvis and Nicotiana attenuate. When Tushingham and her team analyzed samples from 12 pipes and pipe fragments dating from 1,200 years ago to more recent times, they expected to find biomarkers for kinnikinnick. Also called bearberry, ethnobotanic studies suggested the plant was smoked more regularly than tobacco by communities in the region. To Tushingham’s surprise, her team found nicotine in eight of the 12 pipes, but no biomarkers for kinnikinnick. Their find proved to be the longest continuous record of tobacco smoking anywhere in the world, and the results were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in October.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/6b/a16ba15c-0c41-4b7c-a3c6-ea4bb7407ea6/f4large.jpg)

Knowing that indigenous groups were smoking local varieties of tobacco long before European traders came from the East reveals just how important the plant was to traditional practices, Tushingham says. And that kind of knowledge can be particularly beneficial to modern indigenous groups with a higher incidence of tobacco addiction than other groups. The transition from using tobacco for religious and ceremonial purposes to using it recreationally was a dramatic one, launched by curious Europeans who first learned of smoking by establishing colonies in the Americas.

“Once [Europeans] discovered tobacco and smoked it, the desire wasn’t just for its stimulant qualities, but also for its sociability,” says archaeologist Georgia Fox, who works at California State University, Chico, and is the author of The Archaeology of Smoking and Tobacco. “It became a tool in the social world for people to converse and drink and smoke and create relationships.”

And it also became an enormous source of wealth. Before cotton plantations, North America hosted European tobacco plantations—and spurred the start of slavery on the continent, Fox says. Not only did the colonists bring tobacco plants back to Europe and plant it there, they also incorporated it into their relationships with native groups.

“They know indigenous people use tobacco throughout the Americas for diplomatic reasons, so Europeans try to play the same game,” Fox says. “They use it to negotiate. But do they truly understand it? My answer is no.”

The consequences of that commercialized production are still with us today. The World Health Organization estimates around 1.1 billion people are smokers, and more than 7 million die of tobacco use each year. Smoking prevention campaigns can be especially complicated in Native American communities, Tushingham says, because of their long relationship with the plant. She worked with the Nez Perce tribe on her research, in the hopes that better understanding the use of the plant will help with modern public health initiatives. Her research will go towards educational campaigns like Keep Tobacco Sacred, which seeks to place tobacco as a traditional medicine instead of a recreational drug.

To that end, Tushingham and her colleagues are working on identifying which people smoked the most tobacco historically: men or women, low class or high class, old or young. She’s also trying to learn what species of tobacco were smoked at different periods, as the results from her recent paper only showed the biomarker nicotine, which appears in many kinds of tobacco.

Carmody and his colleagues are working on the same questions, though they have a few different puzzles to figure out. In their analysis, they found the biomarkers vanillin and cinnamaldehyde—aromatic alkaloids that they haven’t yet been able to match to any plant. Clearly, the historical practice of smoking was much more intricate than today’s discussions of legalization and prevention.

“We as a discipline have greatly reduced the smoking process to pipes and tobacco,” Carmody says. “And I don’t think that’s the way it probably was in the past.”

What smoking actually looked like—how many plants were used, in what combination, for which ceremonies, by which people—Carmody thinks may never be fully understood. But for now, he’s having fun chasing after smoke trails, teaching us a little about our ancestors along the way.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)