Ancient Egyptian Princess Had Coronary Heart Disease

Coronary heart disease isn’t just a modern problem—even the ancient Egyptians suffered from it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201105201024543687364582_a7b4000236.jpg)

You might be under the impression that hardening of the arteries, a.k.a. atherosclerosis, is a modern problem. That our diets, rich in animal fats and processed foods, are the problem, and if we only ate like humans used to not so long ago, we’d have no need for bypass surgeries and no one would ever die of a heart attack. But atherosclerosis is common in Egyptian mummies, say scientists who imaged dozens in Egypt, going as far back as 1550 B.C. (Their study, recently published in the journal Cardiovascular Imaging, was presented at the International Conference of Non-Invasive Cardiovascular Imaging earlier this week.)

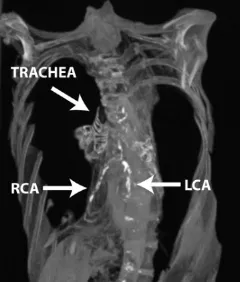

The researchers created CT scans of 52 ancient Egyptian mummies at the National Museum of Antiquities in Cairo (the mummies couldn’t leave, so the scans were done at the museum). They could see arteries in 44 of the mummies. Of those, 20 had calcification, a marker for atherosclerosis, in their arteries, and in three of the mummies that calcification could be seen in coronary arteries.

The mummies with signs of atherosclerosis tended to be those that had lived the longest; they averaged 45 years old. One of the three with coronary heart disease was the princess Ahmose-Meryet-Amon, who lived in Thebes around 1580 to 1530 B.C. and died in her 40s; two of her three main coronary arteries were blocked. If she had lived today, “she would have needed bypass surgery,” said one of the study’s co-authors, Gregory Thomas of the University of California, Irvine. She is now known as the earliest person in history to have suffered from coronary heart disease.

At the time when the princess lived, the Egyptian diet consisted of fruit and vegetables, bread, beer and a little domesticated, lean meat, which may sound like a doctor’s recommendation for how to avoid the very problem the princess had. So how did her arteries end up with so much calcification? The researchers have a couple of theories. Parasitic infections were common in ancient Egypt, and the resulting inflammatory response may have predisposed her body to atherosclerosis, much as HIV appears to do so today. Foods during that time were often preserved in salt, which could have had an adverse effect. Or the princess may have eaten a different diet than the average Egyptian; as a royal, she could have feasted on luxury foods like meat, cheese and butter, the very items that heart doctors tell us to avoid.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)