Arsenic and Old Graves: Civil War-Era Cemeteries May Be Leaking Toxins

The poisonous element, once used in embalming fluids, could be contaminating drinking water as corpses rot

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/be/ffbeef53-32cf-4325-8d8c-053963e8268d/we001711.jpg)

If you live near a Civil War-era cemetery, rotting corpses may be on the attack. While there's no need to fear the walking dead, homeowners should watch out for toxins leaking out of old graves that could be contaminating drinking water and causing serious health problems.

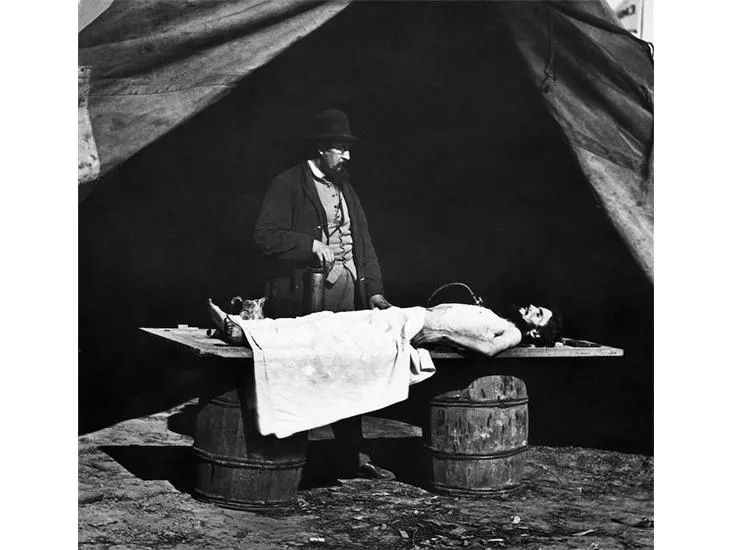

When someone died at the turn of the century, it was common practice to bring a photographer in to take death photos. Also, the people who fought and died in the Civil War came from all over the United States, and families who wanted to bury their kin would pay to have them shipped home.

At the time, ice was the only option to preserve a body, but that didn’t work very well—and no one wants to see a deceased relative partially decomposed.

“We're talking about the 1800s, so how do you freeze [the bodies] and keep them frozen if they take weeks to transport?” says Jana Olivier, an environmental scientist and professor-emeritus at the University of South Africa.

Thus, embalming in the U.S. became a booming industry during the Civil War era. People willing to try their hand at embalming spent their time following the military from combat zone to combat zone.

“Embalmers flocked to battlefields to embalm whoever could afford it and send them home,” said Mike Mathews, a mortuary scientist at the University of Minnesota.

Embalming fluid is effective, but it’s also nasty stuff. Many early recipes for embalming fluid were jealously guarded by morticians because some worked so much better than others, but most commonly contained arsenic, Mathews adds.

One popular formula “contained about four ounces of arsenious acid per gallon of water, and up to 12 pounds of non-degradable arsenic was sometimes used per body,” according to the 5th Street Cemetery Necrogeological Study.

Arsenic kills the bacteria that make corpses stinky—if you’ve ever smelled bad meat, you can imagine how important it is for embalming fluid to do its thing and do it well. But the poisonous element doesn't degrade, so when embalmed bodies rot in the ground, arsenic gets deposited into the soil.

“A Civil War-era cemetery filled with plenty of graves—things seldom stay where you want them to,” says Benjamin Bostick, a geochemist at Columbia University. "As the body is becoming soil, the arsenic is being added to the soil.” From there, rainwater and flooding can wash arsenic into the water table.

That means old cemeteries full of deceased soldiers and civilians present a real problem for today’s homeowners. The federal government says it's only safe for us to drink water with 10 parts per billion of arsenic or less. But in 2002, a USGS-sponsored survey in Iowa City found arsenic levels at three times the federal limit near an old cemetery.

“When you have this big mass of arsenic, there’s enough to affect literally millions of liters of water at least a little bit,” Bostick says.

If humans ingest the contaminated water, it can cause significant health problems over time. Arsenic is a carcinogen that’s associated with skin, lung, bladder and liver cancers, says Joseph Graziano, an environmental health scientist at Columbia University. Drinking arsenic-contaminated water has also been linked to cardiovascular disease, lung disease and cognitive deficits in children.

The good news is that arsenic was banned from embalming fluid in the early 1900s. It was causing health problems for medical students who were operating on embalmed cadavers. Also, the presence of so much arsenic made murder investigations almost impossible. Police couldn’t distinguish between embalming fluid arsenic and cases of murder by arsenic poisoning.

“The state stepped in and said [morticians] couldn’t use arsenic anymore. Boy, they outlawed it real quick,” Mathews says. Now, morticians use a combination of gluteraldehyde and formaldehyde—both chemicals that sterilize—to embalm bodies for open caskets, he adds. These chemicals evaporate away before they pose a risk to the water table.

But if you live near an old cemetery, you should get your well water checked for arsenic and other contaminants every few years, Mathews advises.

“Sadly, much of the population today isn't aware of the hazard that arsenic poses,” Graziano says. “Any homeowner should be testing their well water frequently. We need to be vigilant about hazards from drinking water.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Photo_Bloudoff.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Photo_Bloudoff.jpg)