An Artist Creates a Detailed Replica of Ötzi, the 5,300-Year-Old “Iceman”

Museum artist Gary Staab discusses the art and science of constructing exhibition pieces

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/b0/ffb0c5d0-8ecd-452f-a0ce-8a55baad786a/artist_gary_staab_begins_the_process_of_replicating_otzi_the_iceman_mummy-10.jpg)

It’s a 5,300-year-old murder mystery—the weapon, an arrow; the victim, an ailing male; and the motivation, unknown. Though the perpetrator and the victim are long since dead, scientists and the public remain entranced by the Copper Age story of Ötzi the "Iceman."

In 1991, a pair of hikers spotted the mummy’s head and shoulders poking through the ice in the Ötztal Alps on the Italy-Austria border. But as a response team began digging the body out of the ice, they quickly realized the duo had stumbled on something special. Scientists have since studied every inch of Ötzi—from his ravaged hip to his many curious tattoos.

Ötzi is now locked away in an icy vault in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy. He remains isolated at a chilly 20.3 degrees Fahrenheit to keep bacteria and other contaminants at bay. But he is also kept from the public eye and the larger scientific community, and few have ever viewed the dehydrated flesh of his grisly face in person—until now.

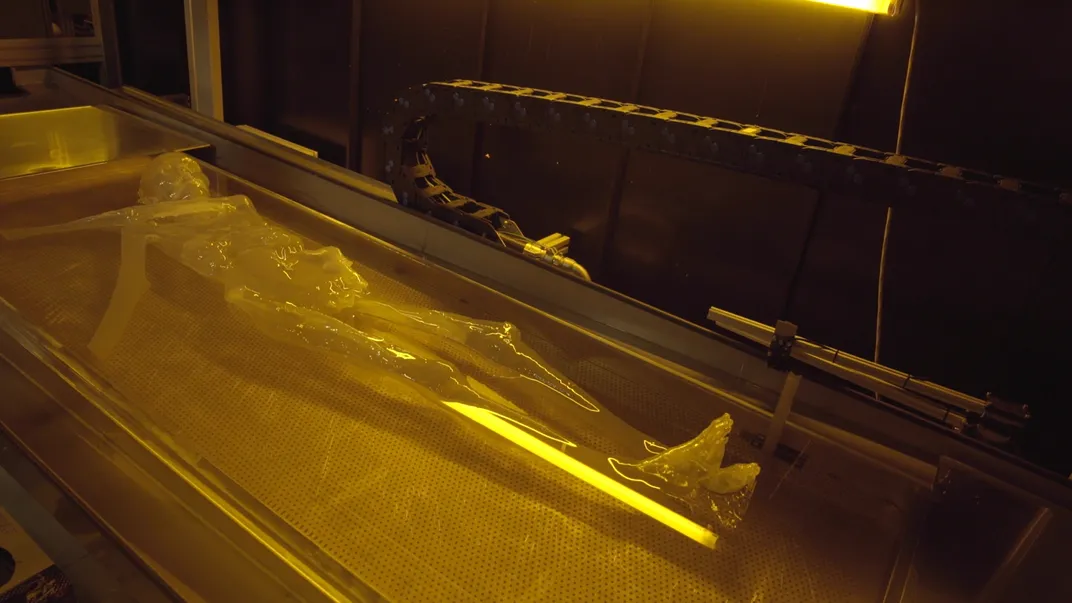

The Dolan DNA Learning Center commissioned world-renowned artist Gary Staab to create three replicas of Ötzi, using medical CAT scans and 3D printing. Staab and his assistants put in around 2,000 man-hours of work over five months to bring the first of these models to life, which is now in display at the center in Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

Iceman Reborn, a new NOVA special premiering tonight, documents how Staab and his team reproduced the figure in minute detail, right down to the texture of his skin. I sat down with the artist to chat a bit about the film and his behind-the-scenes work creating amazing creatures—from tapeworms to extinct giant crocodiles—for museums around the world.

What was it like getting to see Ötzi?

Oh my gosh—it was super powerful. It was a very moving experience.

I’ve worked around a lot of irreplaceable artifacts as a museum person, and there’s a protocol. You don’t want to be the one guy that trips and breaks the Tut mask or something, right? We had to get in scrubs so we didn't bring in any of our own DNA and contaminate Ötzi. Then Marco Samadeli, a lead scientist who has done a lot of the work on Ötzi’s tattoos, lined us all up. He says, “No one touches the mummy.” I thought, of course. But then he points his finger at me and says, “Except for you!” I was just flabbergasted.

Could you walk us through the basic steps of creating these Ötzi replicas?

With any of these really important artifacts or objects, the process starts with negotiation—just getting access. It’s a major event, and the people in charge must trust you enough to give you this very valuable information.

Once we got that all out of the way, we then physically started by taking the digital data [using medical CAT scanning]. But these scans of the Iceman weren’t complete because of his shape—his hands are out to the side. I had to digitally sculpt his hands. When I went into the freezer with him, I took a bunch of high resolution photographs and sandwiched them together to create the 3D shape.

The company Materialise in Leuven, Belgium printed the model. What were some of the details you had to take care of after the 3D model was printed?

The model is just the blank that we start from. We used traditional medical scans, which don’t get surface texture, so we sculpted over the model to create the final skin texture. The top layer of Ötzi’s skin has actually decayed and sloughed off in the water—we had to sculpt that part of it. Of course, we also had to sculpt all of the crazy difficult pathologies and damages that are on the rest of his body. There’s also a lot of additional build that you don’t see in the film. We made thousands of tendons for each one of the models and those had to be glued on independently.

Ötzi also has one eyelash in his left eye, so I took one of mine out and I glued it in there. No one will ever see that, but it’s one of those fun, disturbing things that we do. It’s just what it’s all about: trying to take it to the highest level that you can. Then the entire replica is painted [tatoos and all] to match the best we can.

What was the most challenging part?

There were two parts that were particularly challenging. The first part—that literally gave me nightmares—was reconstructing the hip. [One of Ötzi's hips was ravaged by an animal at some point, so a great deal of his innards are exposed around that area]. In the freezer, we talked about it: ‘Okay, so here’s the lower intestine, here’s the stomach contents spilling out of the lower intestine, here’s the broken bone and marrow structure, here’s a fatty deposit, here’s some dried muscle, here’s a frayed tendon,' and it was just on and on and on. That part took a lot of testing different materials, techniques and colors to figure out.

Then it was the face. I find a huge amount of joy working on faces, because they’re so hard to do. We have an amazing acuity when it comes to judging faces, because we look at them hundreds of times each day. It’s the first thing you engage when you walk into a room—you look into a person's eyes. But, of course, Ötzi's face is kind of aesthetically challenging, because he’s had a hard go of it. He’s been laying on a rock face down for 5,300 years, so his lip is pushed up and his nose squashed. At first glance he’s really horrific looking.

Why is this model important?

Its greatest strength lies in the chance it gives people to experience Ötzi close-up—to compare themselves height-wise, to look him in the eye. You should see people react to it. It’s really, really cool.

How did you first start making these models?

I’ve been ever fascinated with all animal things. But when I went to college, I honestly did not have any idea of what I wanted to do. I took a drawing class as part of my core requirements at Hastings College [in Hastings, Nebraska]. We went to a natural history museum and drew animals in the exhibition, and I sort of had this epiphany: people actually had to build exhibits for museums. When I went back to my dorm, I kept thinking about it. So I drove back to the museum and talked with the director, who said, ‘Well, sure we could do a self-directed study.’ They gave me a job to design my own exhibit case, write it and do all the stuff inside of it. After that I thought, this is it. I’ve been making sculptures for over 25 years and am still madly in love with it. It is an obsessive passion for me.

How is your job different from other artists?

I use all the same skills, it’s just a different final result. I’m trying to build something that is really believable—something that’s essentially a scientific display model. It’s not a fine art piece. A fine artist or painter wants to leave their mark on the work. But in my job that’s the worst possible thing I could do. If I do a good job, then no one ever knows that I was there.

What do you like about your work?

I do it because I learn a lot, and I love the diversity of things that come through—everything from building enlarged models of microscopic life to dinosaurs and early hominids. I get to study so many different things.

I also find the physical act of making stuff is such a great memory aid. If you want to learn something, you draw it. If you want to know it, you sculpt it. If you have to physically make it in three-dimensions, that burns it into your memory and those facts stay hard and fast.

What has been your favorite model to work on?

One of the neatest projects was this 40-foot long extinct crocodile, Sarcosuchus imperator. National Geographic did a documentary on it and nicknamed it "Supercroc"—it’s got like a six-foot-long skull. That was a really cool project because it allowed me to go out in the field with some crocodilian biologists. We snared crocodiles and measured them.

That said, I just feel eternally lucky and privileged to be asked to work on these things and to get access to these cultural icons. I have to say it has always kind of been a dream of mine to go in the freezer with the Iceman. When they actually said we were going in there, I couldn’t believe it. And then to get such special treatment was the highlight of my life, to be honest. It’s been amazing.

Ötzi's first doppelgänger is now on display at the DNA Learning Center. The second mummy will be used in a traveling exhibition, before joining the true Iceman at the South Tyrol Museum in Italy. The third replica will eventually be part of an exhibition in New York, but the location has not yet been determined.

The special Iceman Reborn will air on PBS on February 17, 2016 at 9PM EST.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)