Bringing the Wood Bison Back to Alaska

Once nearly extinct, the subspecies is set to return to the United States

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/80/498074b7-964a-402b-8641-e48a83daffd2/42-61007919.jpg)

Wood bison aren’t the most accommodating of animals. When bothered, these super-sized versions of America’s sweetheart, the plains bison, can become as solid as Stonehenge, refusing to budge, or they might take off running—at up to 40 miles per hour. It’s an impressive feat for North America’s largest land mammal (bulls weigh up to 2,600 pounds), but it’s exactly the type of balky behavior that Tom Seaton, a mukluks-wearing biologist with Alaska’s fish and game department, is trying to avoid.

Beginning later this month, Seaton will chaperon 100 bison, bred to be genetically diverse to boost their shot at survival, across nearly 400 miles to a new home in Alaska’s wilderness, where they have not lived in the wild for more than a century.

Some 150,000 wood bison or more once roamed the boreal forests of Alaska and northwestern Canada, grazing in meadows between vast expanses of trees (thus the “wood” in their name). But overhunting, habitat loss and interbreeding with plains bison wiped out the wood bison, except for just 200 or so near the border of Alberta and the Northwest Territories.

Now they’re coming back. Following a successful population recovery program in Canada, biologists brought the bison into the States, transferring beasts from Canada’s healthy stock and breeding them at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center, outside Anchorage.

Making the trip in Seaton’s care are 50 cows (many pregnant), 20 two-year-olds and 30 calves. They’ll travel most of the way by cargo plane. A restless bison is quite a force, so they’ll be packed in retrofitted steel shipping containers that restrict their movement. The final leg, though just five miles, could take a day or more. The bison, led by Seaton and a small crew, will hoof it across the frozen Innoko River. Full-size bulls confined in containers could become anxious, and brawly after deplaning, so they’ll arrive by barge in May or June.

If all goes well, by later this year, the bison will be feeding across 500 square miles between the Innoko and Yukon rivers. Biologists say the grazing will break up the coarsest grasses, clearing the way for the return of birds and small mammals that prefer a more open habitat.

Once the herd grows in size, native Alaskans living in four villages surrounding the range will be allowed to hunt the animals for food. Local kids from the village of Anvik, according to letters to the U.S. government in support of the project, are already looking forward to a break from moose.

First, though, the bison have to get there. “We have to be adaptable,” says Seaton. “Bison aren’t following the rules.”

Related Reads

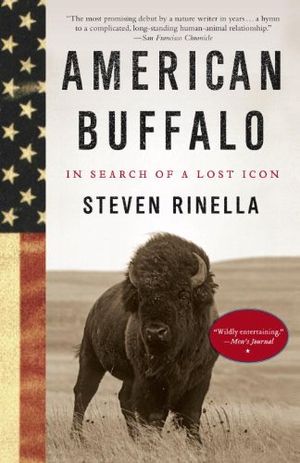

American Buffalo: In Search of a Lost Icon