Chinese Cave Graffiti Records Centuries of Drought

And chemical clues in a stalagmite inside the cave confirm the chronicles on the walls

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/bc/edbc0799-fbb2-417d-a830-52035f96ab47/1894_credit_l_tan.jpg)

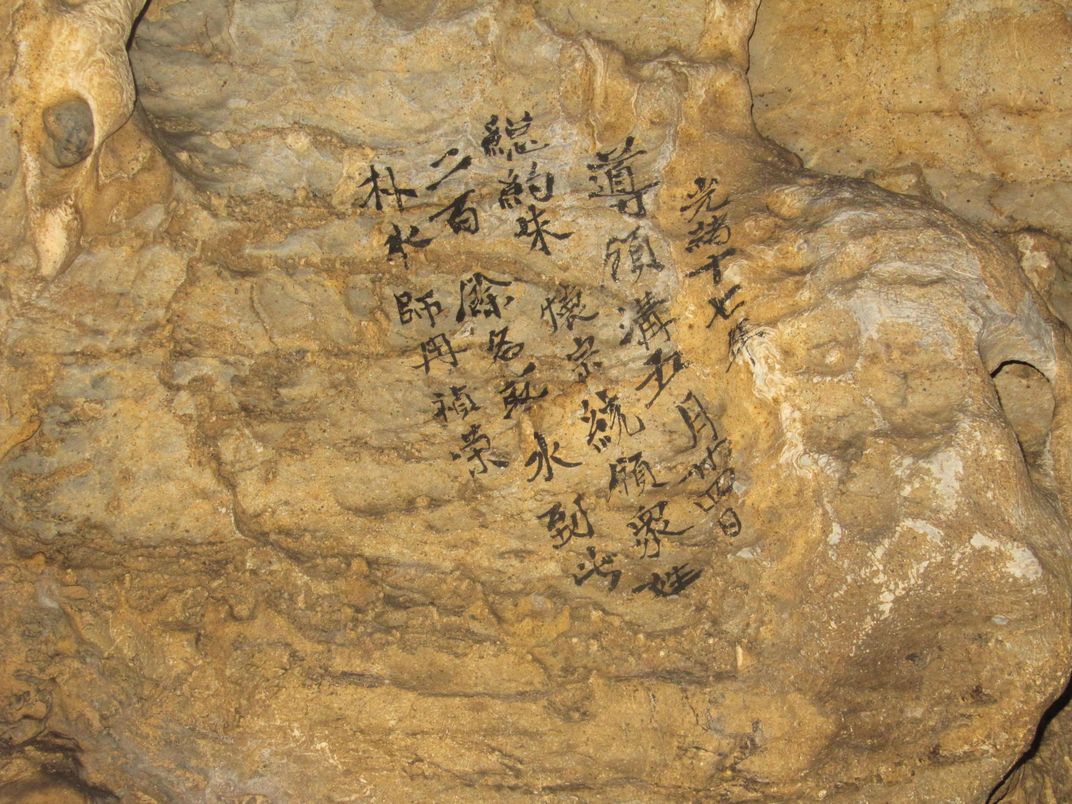

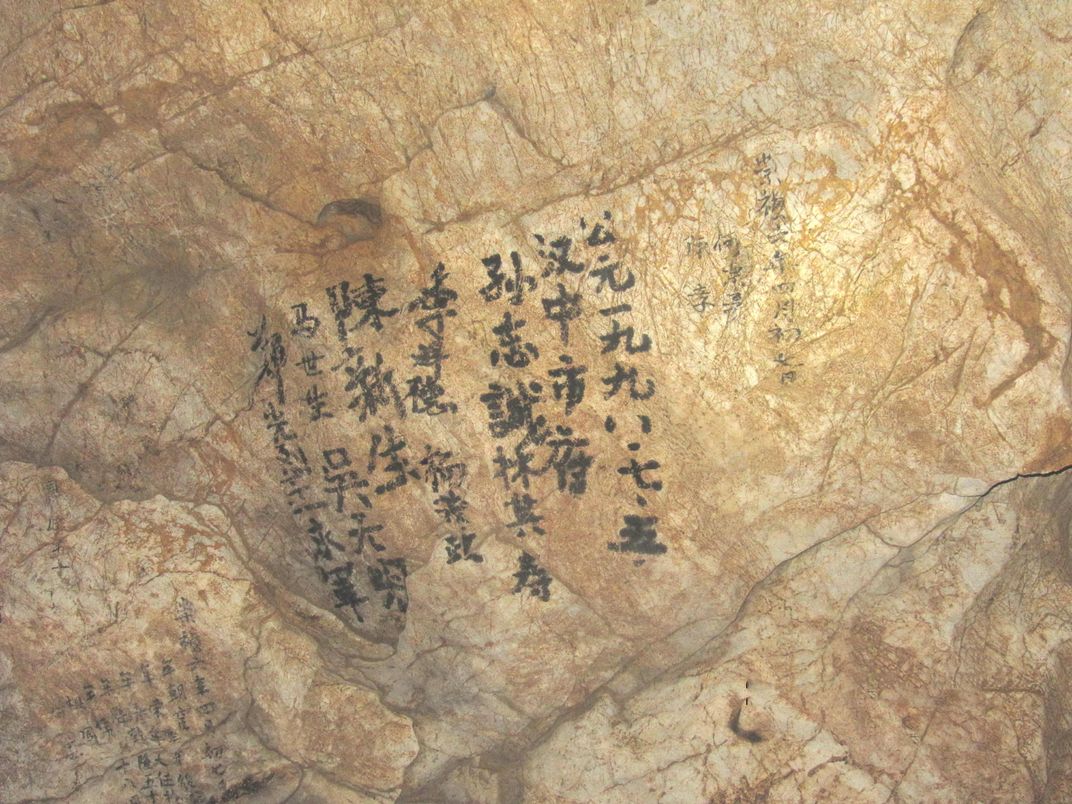

For at least the last five centuries, people from the region near the Qinling Mountains in central China went into Dayu Cave to retrieve water and pray. Some of them marked their visits with graffiti—bold black text against the yellow-brown walls—that recorded the droughts that sent them to the cave’s Dragon Lake. Now scientists have matched those chronicles with chemical data compiled from the cave itself and found evidence that more hard times could be ahead.

Liangcheng Tan of the Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered the inscriptions by accident in 2009 when he and his colleagues visited the cave to collect samples of mineral deposits called speleothems. Graffiti on the walls recorded at least 70 visits to the cave by locals. Seven inscriptions were special, though, and noted events tied to droughts in the 1500s, 1700s and 1800s. For instance, one reads: “On June 8, 46th year of the Emperor Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty [or July 7, 1707 on the Western calendar], the governor of Ningqiang district came to the cave to pray for rain.”

Humans around the world have marked their visits to caves with graffiti, but these are the first known cave writings to record details about drought, Tan says.

Even without graffiti, caves can hold records of local climate. Rain trickles through the rocks above, dripping into the cave and creating stalactites and stalagmites. The water carries oxygen, carbon and other elements that get incorporated into the cave deposits over time. Similar to the technique of examining tree rings, analyzing those deposits for ratios of various elements or their isotopes can help scientists determine past climate events, including droughts. Tan and his colleagues found a stalagmite less than a mile from the cave’s entrance that covered the period from 1265 to 1982. Analyzing it revealed that each drought recorded in graffiti matched up with changes in the composition of the mineral deposits.

“It’s very interesting that people came in such large groups of 100 and more to pray for rain, and repeatedly so. Also, it’s amazing that the geochemical reconstruction follows so closely the historical evidence,” says Sebastian Breitenbach of the University of Cambridge, one of the coauthors on the paper, published today in Scientific Reports.

The historical droughts are known to have been devastating to the region. Droughts in the 1890s, for instance, led to social unrest and a conflict between civilians and the government in 1900. And the 1528 event saw harvests fail for two years in a row. Many people starved to death, and some of those who survived resorted to cannibalism.

Using the stalagmite data, the researchers extrapolated how patterns of precipitation might change in the region through 2042. Their model predicts a drought in the 1990s—which matches instrumental data for that time—and another one in the late 2030s.

“We find in our record a stark reminder of the influence climate has on us as society, and the vulnerability of civilization to even relatively small changes in climate,” says Breitenbach. “That our highly industrialized lifestyle is quite different from pre-industrial society in China is clear, but bearing the drought in California in mind, it is evident that sustained shifts in hydrological pattern can very severely impact large populations.” And even if the local people are not affected, future droughts could threaten panda habitat in the Qinling Mountains, he notes.

Such events probably won’t be recorded in Dayu Cave, though. People still go to the cave to get water when there’s a severe drought, Tan notes. But to protect the cave, no one is allowed to write on the walls.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)