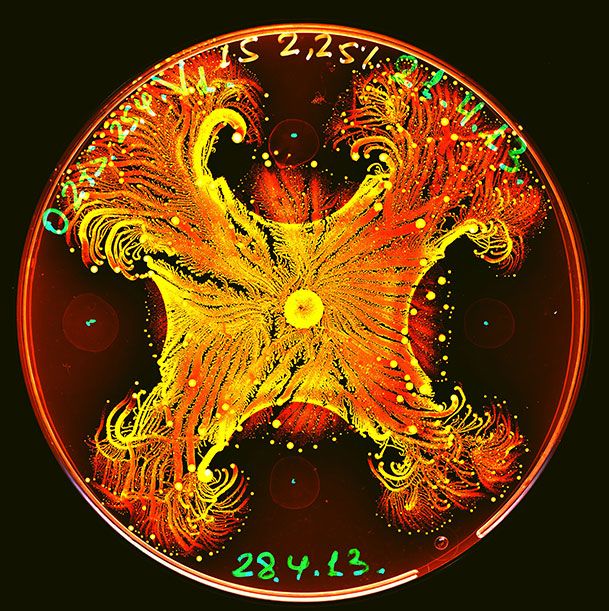

Colonies of Growing Bacteria Make Psychedelic Art

Israeli physicist Eshel Ben-Jacob uses bacteria as an art medium, shaping colonies in petri dishes into bold patterns

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Collage-Psychedelic-bacteria.jpg)

In the early 1990s, Eshel Ben-Jacob, a biological physicist at Tel Aviv University, and his colleagues discovered two new species of bacteria—Paenibacillus dendritiformis and Paenibacillus vortex. Both strains of soil bacteria, the species live near the roots of plants.

Each bacterium is only a few microns in size, and they divide every 20 minutes, ultimately forming large colonies consisting of billions of microorganisms. “The entire colony can be thought of as a big brain, a super brain, that receives signals, processes information and then makes decisions about where to send bacteria and where to continue to expand,” says Ben-Jacob.

In his lab, Ben-Jacob grew the bacteria in petri dishes and exposed them to different conditions—like temperature swings, for instance—in an attempt to imitate some of the variability in the natural environments where the bacteria grow. “The idea was very simple,” he explains.”If you want to see their capabilities, you have to expose them to some challenges.” The physicist could see how the colony responded to the stress of different variables.

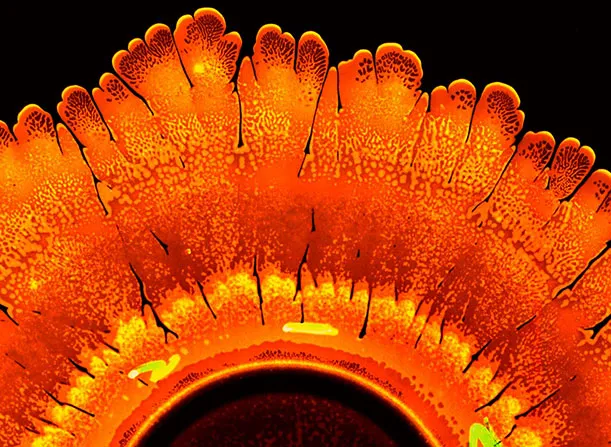

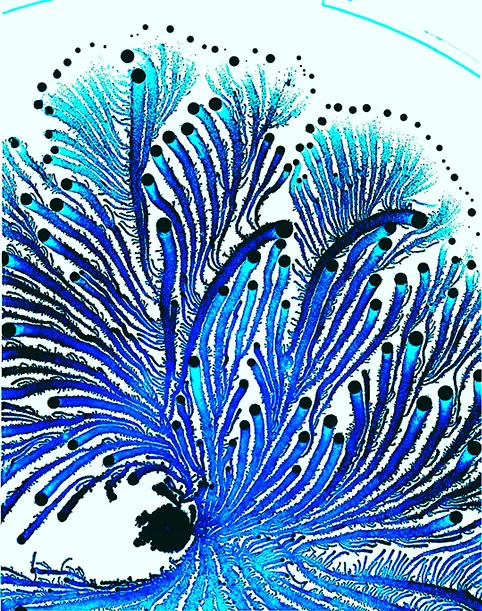

As opposed to letting the bacteria grow in uniform conditions, for scientific purposes, he might let them grow at one temperature in an incubator, take them out, expose them and then put them back in the incubator. He also, at times, added antibiotics and other treatments to the petri dishes in order to incite a physical response. The bacteria, it turned out, communicated with one another in response to these stressors; they secreted lubricants, allowing them to move, and formed elaborate patterns with dots and vine-like branches.

From the first instant he saw a colony, Ben-Jacob called it bacteria art. ”Without knowing anything, you’ll feel the sense that there is drama going on,” he says.

In time, Ben-Jacob came to understand the behaviors of the bacteria. And, he says, “If you understand how they grow, then you can use it as a material for doing art.” Having some say in the pattern the colony takes just requires some manipulation on the scientist’s part. “In order to let the bacteria express their art, you have to learn to speak the bacteria’s language,” Ben-Jacob adds.

The bacteria are naturally colorless. To make them visible, Ben-Jacob uses a stain called Coomassie blue to dye the microorganisms. The bacteria take on different shades of blue depending on each individual bacterium’s density. Then, working with photographs of the colonies in Photoshop, the scientist translates the blues into a spectrum of any color of his choosing.

“If you take the same object and you change the lights and the colors, it triggers different perception in our brain,” says Ben-Jacob. “In some cases, just coloring it and looking at it helped me to realize a few things, some clues that we could then use in order to understand how they develop the patterns.” The images have helped him see how bacteria cooperate to meet challenges—bacteria in one part of a colony can sense something in the local environment and send messages to bacteria in other parts of the colony. The bacteria might encounter food, for example, and manage to communicate to other members of the colony that it is present, so that it can be digested. In other words, the science informs the art which sometimes then informs the science again.

The patterns in Ben-Jacob’s bacteria art are eye-catching and evocative—without knowing how they formed, the brain leaps to the familiar seaweeds, corals, sphagnum moss, feathers—fractal displays that border on the psychedelic. A large part of the series’ visual appeal comes from the push-pull of order and disorder in the images, the scientist-artist claims.

“The bacteria have to maintain order, but they also have to maintain flexibility, so that when conditions change they can better adapt to the environment,” says Ben-Jacob. “We have an affinity for things that have the combination of the two, order and disorder. If you analyze classical music, it is the same thing. The things that we really like and are captivated by are things that have this mixture.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)