Coral Bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef May Get a Lot Worse in the Future

Climate change could alter temperature patterns in a way that stops corals from preparing for bleaching events

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/86/698659ed-b2bb-4f1c-9a20-578ca23842ea/ainsworth2hr-wr.jpg)

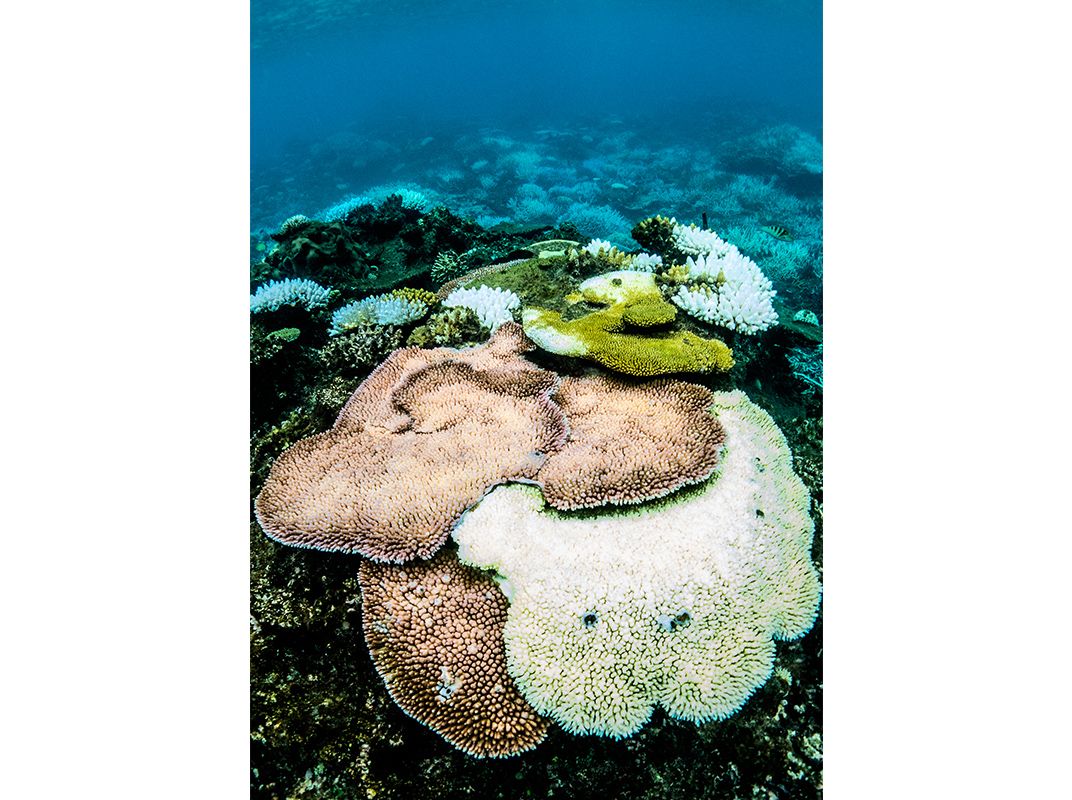

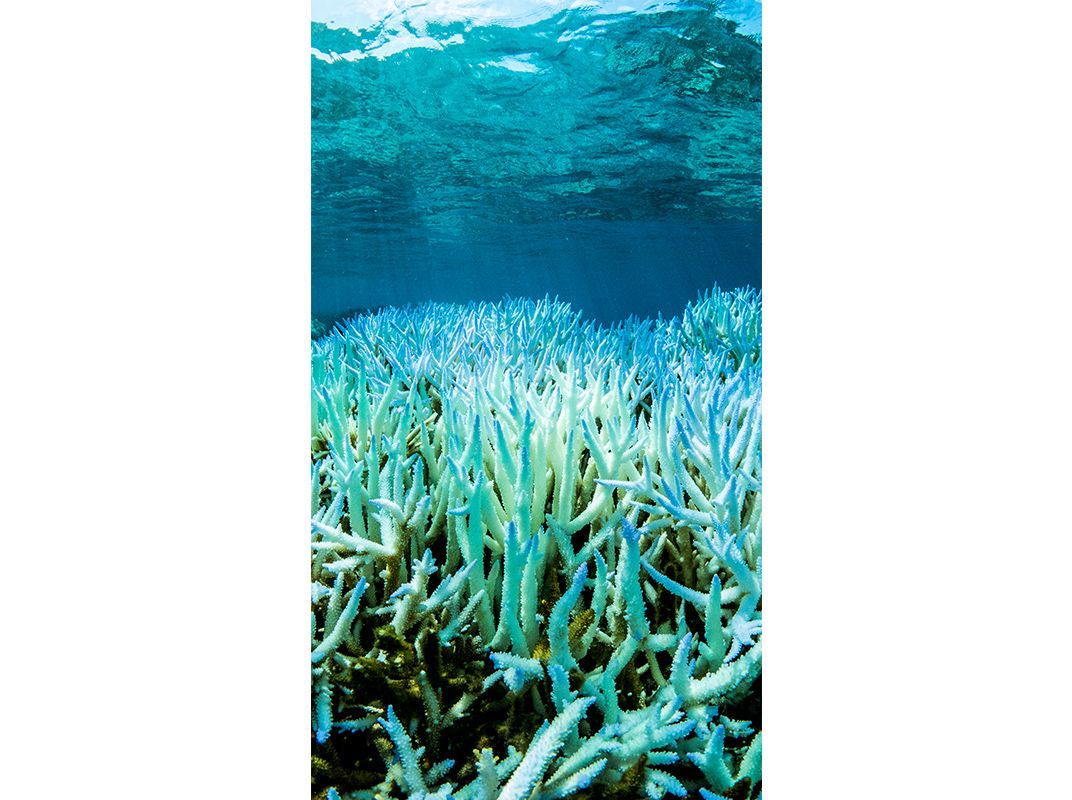

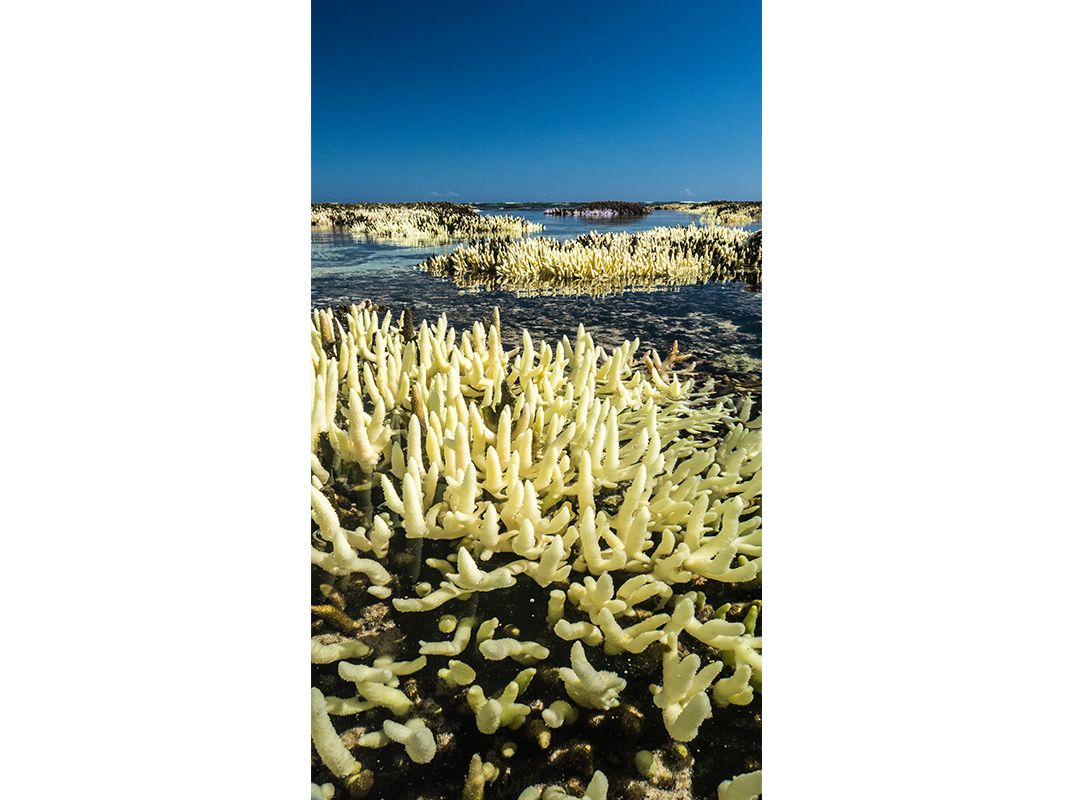

A massive coral bleaching event has struck the Great Barrier Reef, with at least half of the GBR’s length affected. Scott Heron, of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch, calls it “the worst observed bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef.” This could lead to mass death of corals, risking the future of a unique ecosystem that stretches 1,400 miles along the coast of Australia and is home to thousands of species of fish, invertebrates and marine mammals.

The future could be even worse, though.

Heron was part of a team of scientists, led by Tracy Ainsworth of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, that has discovered a mechanism by which corals can prepare themselves for bleaching events. But they also found that climate change could soon erase the temperature patterns that allow corals to implement that mechanism before an event occurs.

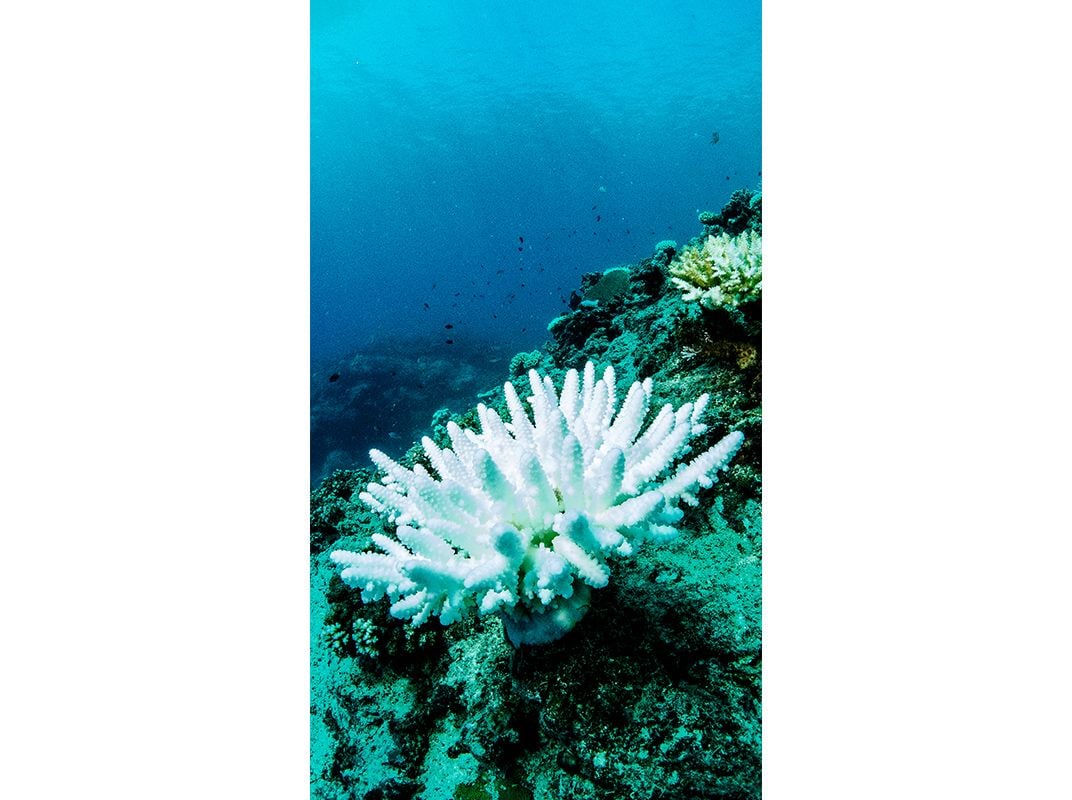

“Coral is an animal that has a plant living inside its cells,” explains Ainsworth. That plant, an algae that gives coral its distinct color, provides most of the animal’s nutrition. But when waters get too hot, the coral can expel the algae, revealing the white skeleton beneath the living coral and, often, killing the coral animal. The pale color is what gives it the term “bleaching.”

But temperatures don’t simply rise and rise steadily until coral bleaching occurs. Sometimes that happens. But other times, the water can get hotter, though not quite hot enough to start bleaching, and then fall back down for about 10 days before rising again above the critical bleaching temperature. This temperature pattern, Ainsworth and her colleagues report today in Science, is a common one on the GBR. The researchers named it the “protective trajectory” because, in such circumstances, it spurs coral to implement measures that protect them from a bleaching event and better survive it.

The researchers examined 27 years of coral reef records for the GBR and looked for times when local water temperatures rose high enough to cause bleaching, called “thermal stress events.” They found that 75 percent of these events occurred with the temperature pattern that proved protective for the corals, rising, then falling, then rising again. In 20 percent of the events, temperatures rose steadily, with corals having no time to prepare for the hot waters that trigger bleaching, and in 5 percent, corals were subjected to two temperature peaks that resulted in bleaching.

Bleaching still occurred when Acropora aspera corals, a common reef-building species, experienced the protective pattern of temperatures, but the extent was lower than what was seen during the other two temperature patterns, the team found. The ramp-up in temperature allowed the corals to implement protective measures and prepare themselves for even warmer waters, gene analyses found. They initiate heat shock responses that organisms use to protect cells from heat, and these processes are then up and running when the really dangerous heat comes.

“It’s like a practice run,” Ainsworth says. “Doing training doesn’t stop a marathon from being incredibly difficult to finish. It just makes your body better able to handle it.” And if you stretch out that run too long or have to go up too many hills, you still won’t be able to finish. It’s the same with the corals. Stretch out a heat even too long or have temperatures rise too hot, and the corals still bleach and die.

The current bleaching event actually follows the temperature patterns found in the new study, Heron notes. “It’s about three-quarters of the events [in 2016] that had the protective shape. The bad news is that the stress has been high and long.” El Niño has driven April temperatures to be more like those typically seen in February, in the height of the Australian summer.

The researchers projected into the future, determining what would happen as climate change drove water temperatures up. “Our hope was that [the protective pattern] would increase into the future,” Heron says. “However, our study showed that the proportion of events with that protection mechanism is actually modeled to decrease.”

If sea surface temperatures rise by 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100, only 22 percent of the bleaching events would fall within that protective pattern, the analysis found.

“It’s a really neat study, and I think it’s just the right time,” says marine ecologist Stephen Palumbi of Stanford University. It shows that the big problem for coral bleaching is not necessarily the heat itself but how fast it shows up. The slow heating events the Great Barrier Reef now experiences could soon turn into “earthquakes of heat,” he notes, that corals won’t have time to prepare for.

“I think we shouldn’t lose hope, though,” says Ainsworth. Her team’s analysis showed that reefs that tend to experience the protective temperature pattern could have enough time to evolutionarily adapt to warmer waters. Those reefs might also be good targets for special protective measures.

However, Palumbi says, “every place you go in this entire argument, you still come back to the need to reduce [carbon dioxide] addiction.” Because, he notes, even if corals survive warmer waters, there’s still the problem of ocean acidification hovering in the future.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)