The Creepy, Kitschy and Geeky Patches of US Spy Satellite Launches

There may be method to the madness behind the outlandish designs of the National Reconnaissance Office mission patches

:focal(378x115:379x116)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/fc/8dfc4c4a-5f53-43e1-b488-afafc2188538/purple.jpg)

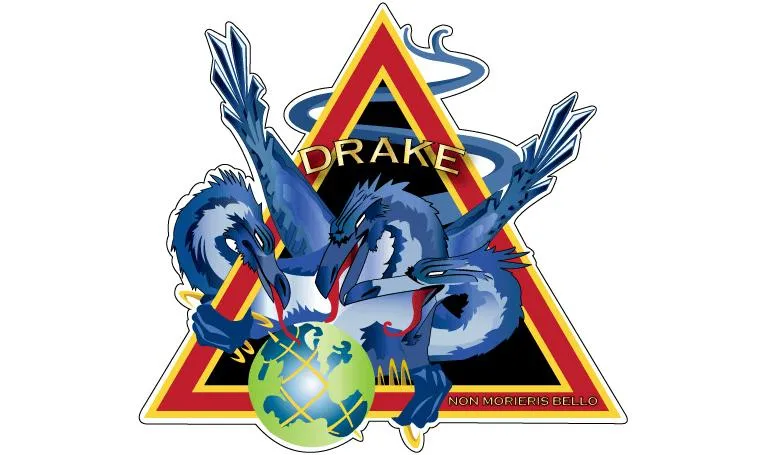

A purple-haired sorceress holding a fireball. A three-headed dragon wrapping its claws around the world. A great raptor emerging from the flames.

No, these are not characters from a Magic: The Gathering deck. They are avatars depicted on the official mission patches made for the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). Just as NASA creates specially designed patches for each mission into space, NRO follows that tradition for its spy satellite launches. But while NASA patches tend to feature space ships and American flags, NRO prefers wizards, Vikings, teddy bears and the all-seeing eye. With these outlandish designs, a civilian would be justified in wondering if NRO is trolling.

Unfortunately, given the agency's extreme secrecy, it’s impossible to answer that question for sure. But based on information that has been leaked about some of the patches, it seems there may be a method to the artistic madness.

Forged in Secret

Understanding the patches requires a trip back to the 1960s and the early days of the human space program, explains Robert Pearlman, a space historian and the founder of collectSPACE. At the time, NASA allowed its astronauts to name their spacecraft. John Glenn chose Friendship 7, for example, for the Mercury space capsule he piloted when he became the first US astronaut to orbit Earth. Gordon Cooper went with Faith 7 for his spacecraft during the final mission of the Mercury program.

When it came time to launch the Gemini program, however, NASA decided to take away the naming privilege. The astronauts, understandably, were disappointed. So Gemini pilot Cooper asked NASA if they’d be willing to compromise and—in the tradition of military squadrons—allow the crew to design a patch instead. NASA agreed, and since then patches have become a staple for both crewed and robotic NASA flights.

NRO arrived on the space launch scene around the same time that NASA’s first patches were being designed. In 1960, former president Dwight D. Eisenhower established the agency as a central authority for organizing the nation’s reconnaissance operations, and oversight of reconnaissance imaging satellites—spy satellites, in popular parlance—was a big part of that mission. Right from the start, NRO operations were all very cloak-and-dagger. The public didn’t even learn about the agency’s existence until 1971, and its first reconnaissance satellite program, Corona, wasn’t declassified until 1995. “The reconnaissance satellites have been a factor of the space program since the very beginning,” Pearlman says. “But they are indeed classified, and their capabilities are classified.”

Today NRO launches about four to six satellites per year, including the NROL-35 mission, with the patch seen above, slated to fly this Thursday. The public still doesn't know exactly what each satellite is doing, but for a couple decades now the agency has advertised the date and time of its launches—probably because, as Pearlman points out, “it’s hard to hide a rocket.” In response, a subculture of fervent hobbyists has become committed to watching the skies at night, piecing together the satellites’ orbits. At some point, those hobbyists discovered that—just like NASA—NRO also issues mission patches. The agency didn’t seem to care if the patches were leaked, and eventually it even started publishing depictions of the patches along with launch announcements. Even so, for years knowledge of the patches largely remained confined to enthusiasts, especially in the days prior to widespread social media.

Public Debut

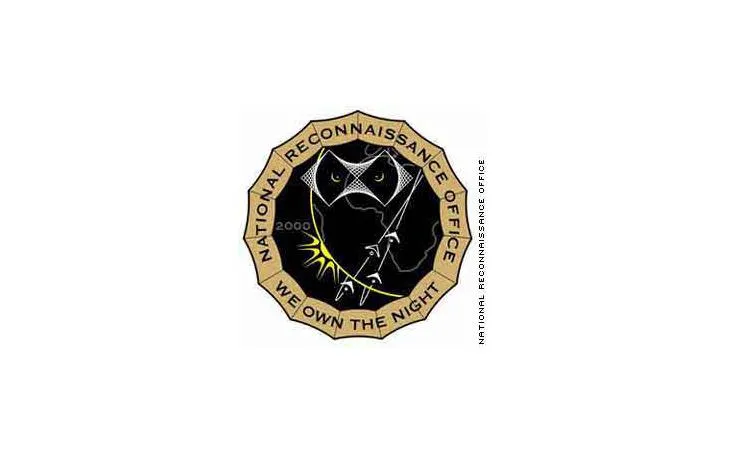

The patches’ relative obscurity changed in 2000, with the launch of a payload known as NROL-11. The mission patch depicted what appeared to be owl eyes peering down at the Earth, where four arrow-shaped vectors, two per orbit, made their way across Africa. Three of the vectors were white, and one was dark. Based solely on studying the design, civilian satellite watcher Ted Molczan hypothesized that the patch showed a failed satellite (the dark vector), and that the newly launched satellite would take its place.

Sure enough, after the launch a new satellite appeared just where Molczan predicted. Pearlman, who reported on the story at the time, says that NRO at first told him “no comment” when he contacted them. About 30 minutes later they called him back and asked him not to publish the story. Pearlman told them no dice, and in the end, the NRO spokesman told him that the patches were just morale-builders for those who work on the launches.

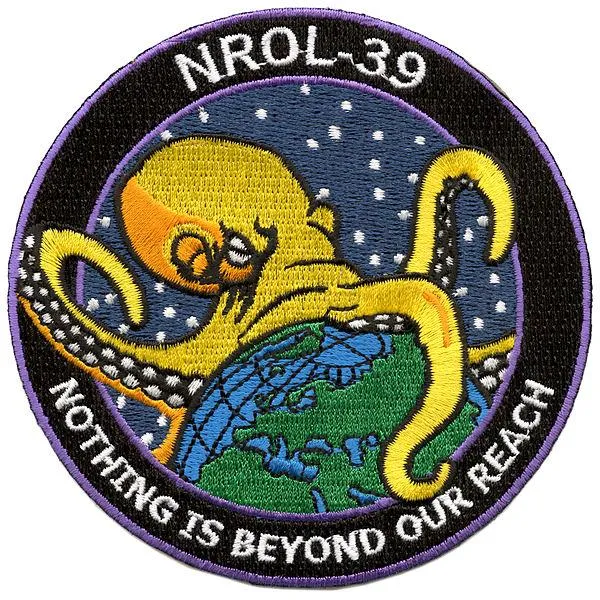

Whether NRO admits it, though, it seemed that NROL-11’s patch had inadvertently revealed classified details about its payload’s whereabouts, and when the story broke, the patches suddenly appeared on the public’s radar. Although the patches were under more scrutiny than ever before, the agency didn’t flinch. Rather than classify them or discontinue the tradition, NRO ramped up its game. Subsequent designs became even more ridiculous, featuring patriotic gorillas or 16th-century ships, for example. The public ate it up. Some—like the 2013 mission heralded by a giant Earth-eating octopus—sparked their own media frenzies, and rip-offs of the most popular designs popped up for sale online. NRO’s new motto seems to be “better to have a more outlandish design than show actual details about the flight,” Pearlman says.

As for their motivations, Pearlman doesn’t think they’re in it just for the lolz. “No, I don’t think they’re playing us,” he says. “If anything, it’s an internal gag. Like, how far can you take it without being reprimanded? Or maybe the patches represent jokes that cropped up in the processing of the satellites, which we’ll never know unless they’re declassified—and maybe not even then.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)