Creepy or Cool? Portraits Derived From the DNA in Hair and Gum Found in Public Places

Artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg reconstructs the faces of strangers from genetic evidence she scavenges from the streets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/71/55715c4b-5281-4f4b-833b-83db7be5962a/heather-dewey-hagborg-self-portrait.jpg)

It started with hair. Donning a pair of rubber gloves, Heather Dewey-Hagborg collected hairs from a public bathroom at Penn Station and placed them in plastic baggies for safe keeping. Then, her search expanded to include other types of forensic evidence. As the artist traverses her usual routes through New York City from her home in Brooklyn, down sidewalks onto city buses and subway cars—even into art museums—she gathers fingernails, cigarette butts and wads of discarded chewing gum.

Do you get strange looks? I ask, in a recent phone conversation. “Sometimes,” says Dewey-Hagborg. “But New Yorkers are pretty used to people doing weird stuff.”

Dewey-Hagborg’s odd habit has a larger purpose. The 30-year-old PhD student, studying electronic arts at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, extracts DNA from each piece of evidence she collects, focusing on specific genomic regions from her samples. She then sequences these regions and enters this data into a computer program, which churns out a model of the face of the person who left the hair, fingernail, cigarette or gum behind.

It gets creepier.

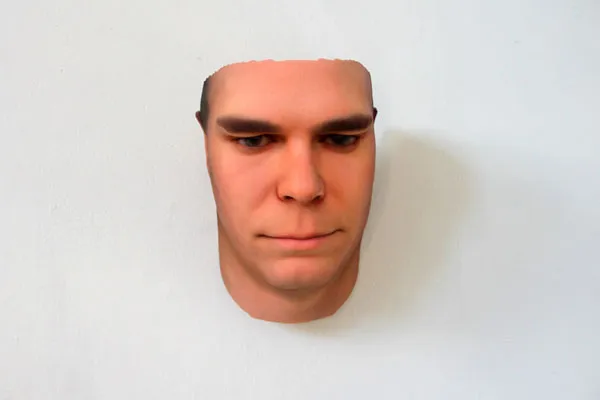

From those facial models, she then produces actual sculptures using a 3D printer. When she shows the series, called “Stranger Visions,” she hangs the life-sized portraits, like life masks, on gallery walls. Oftentimes, beside a portrait, is a Victorian-style wooden box with various compartments holding the original sample, data about it and a photograph of where it was found.

Rest assured, the artist has some limits when it comes to what she will pick up from the streets. Though they could be helpful to her process, Dewey-Hagborg refuses to swipe saliva samples and used condoms. She tells me she has had the most success with cigarette butts. “They really get their gels into that filter of the cigarette butt,” she says. “There just tends to be more stuff there to actually pull the DNA from.”

Dewey-Hagborg takes me step-by-step through her creative process. Once she collects a sample, she brings it to one of two labs—Genspace, a do-it-yourself biology lab in Brooklyn, or one on campus at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. (She splits her time between Brooklyn and upstate New York.) Early on in the project, the artist took a crash course in molecular biology at Genspace, a do-it-yourself biology lab in Brooklyn, where she learned about DNA extraction and a technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR). She uses standard DNA extraction kits that she orders online to analyze the DNA in her samples.

If the sample is a wad of chewing gum, for example, she cuts a little piece off of it, then cuts that little piece into even smaller pieces. She puts the tiny pieces into a tube with chemicals, incubates it, puts it in a centrifuge and repeats, multiple times, until the chemicals successfully extract purified DNA. After that, Dewey-Hagborg runs a polymerase chain reaction on the DNA, amplifying specific regions of the genome that she’s targeted. She sends the mitochondrial amplified DNA (from both mitochondria and the cells’ nuclei) to a lab to get sequenced, and the lab returns about 400 base pair sequences of guanine, adenine, thymine and cytosine (G, A, T and C).

Dewey-Hagborg then compares the sequences returned with those found in human genome databases. Based on this comparison, she gathers information about the person’s ancestry, gender, eye color, propensity to be overweight and other traits related to facial morphology, such as the space between one’s eyes. “I have a list of about 40 or 50 different traits that I have either successfully analyzed or I am in the process of working on right now,” she says.

Dewey-Hagborg then enters these parameters into a computer program to create a 3D model of the person’s face.” Ancestry gives you most of the generic picture of what someone is going to tend to look like. Then, the other traits point towards modifications on that kind of generic portrait,” she explains. The artist ultimately sends a file of the 3D model to a 3D printer on the campus of her alma mater, New York University, so that it can be transformed into sculpture.

There is, of course, no way of knowing how accurate Dewey-Hagborg’s sculptures are—since the samples are from anonymous individuals, a direct comparison cannot be made. Certainly, there are limitations to what is known about how genes are linked to specific facial features.”We are really just starting to learn about that information,” says Dewey-Hagborg. The artist has no way, for instance, to tell the age of a person based on their DNA. “For right now, the process creates basically a 25-year-old version of the person,” she says.

That said, the “Stranger Visions” project is a startling reminder of advances in both technology and genetics. “It came from this place of noticing that we are leaving genetic material everywhere,” says Dewey-Hagbog. “That, combined with the increasing accessibility to molecular biology and these techniques means that this kind of science fiction future is here now. It is available to us today. The question really is what are we going to do with that?”

Hal Brown, of Delaware’s medical examiner’s office, contacted the artist recently about a cold case. For the past 20 years, he has had the remains of an unidentified woman, and he wondered if the artist might be able to make a portrait of her—another clue that could lead investigators to an answer. Dewey-Hagborg is currently working on a sculpture from a DNA sample Brown provided.

“I have always had a love for detective stories, but never was part of one before. It has been an interesting turn for the art to take,” she says. “It is hard to say just yet where else it will take me.”

Dewey-Hagborg’s work will be on display at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute on May 12. She is taking part in a policy discussion at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. on June 3 and will be giving a talk, with a pop-up exhibit, at Genspace in Brooklyn on June 13. The QF Gallery in East Hampton, Long Island, will be hosting an exhibit from June 29-July 13, as will the New York Public Library from January 7 to April 2, 2014.

Editor’s Note: After getting great feedback from our readers, we clarified how the artist analyzes the DNA from the samples she collects.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)