Curiosity Discovers a New Type of Martian Rock That Likely Formed Near Water

The rock closely resembles mugearites, which form after molten rock encounters liquid water

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130926010154rock-copy.jpg)

Some 46 Martian days after landing on Mars in August 2012, after traveling nearly 1,000 feet from its landing site, Curiosity came upon a pyramid-shaped rock, roughly 20 inches tall. Researchers had been looking for a rock to use for calibrating a number of the rover’s high-tech instruments, and as principal investigator Roger Wiens said at a press conference at the time, “It was the first good-size rock that we found along the way.”

For the first time, scientists used the rover’s Hand Lens Imager (which takes ultra-high resolution photos of a rock’s surface) and the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (which bombards a rock with alpha particles and X-rays, kicking off electrons in patterns that allow scientists to identify the elements locked within it). They also used the ChemCam, a device that fires a laser at a rock and measures the abundances of elements vaporized.

Curiosity, for its part, commemorated the event with a pithy tweet:

I did a science! 1st contact science on rock target Jake. Here's an action shot pic.twitter.com/pzcgH6Bk

— Curiosity Rover (@MarsCuriosity) September 22, 2012A year later, the Curiosity team’s analysis of the data collected by these instruments, published today in Science, shows that they made a pretty lucky choice in finding a rock to start with. The rock, dubbed “Jake_M” (after engineer Jake Matijevic, who died a few days after Curiosity touched down), is unlike any rock previously found on Mars—and its composition intriguingly suggests that it formed after molten rock cooled quickly in the presence of underground water.

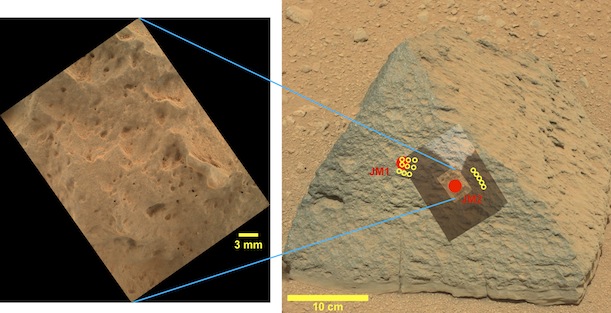

The high-resolution image of Jake_M on the left was taken by the Hand Lens Imager, while the APXS analyzed the rock at the locations marked by two red dots, and the ChemCam at the small yellow circles. Image via NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory/Malin Space Science Systems

The new discovery was published as part of a special series of papers in Science that describe the initial geologic data collected by Curiosity’s full suite of scientific instrumentation. One of the other significant findings is a chemical analysis of a scoop of Martian soil—heated to 835 degrees Celsius inside the Sample Analysis at Mars instrument mechanism—showing that it contains between 1.5 and 3 percent water by weight, a level higher than scientists expected.

But what’s most exciting about the series of findings is the surprising chemical analysis of Jake_M. The researchers determined that it is likely igneous (formed by the solidification of magma) and, unlike any other igneous rocks previously found on Mars, has a mineral composition most similar to a class of basaltic rocks on Earth called mugearites.

“On Earth, we have a pretty good idea how mugearites and rocks like them are formed,” Martin Fisk, an Oregon State University geologist and co-author of the paper, said in a press statement. “It starts with magma deep within the Earth that crystallizes in the presence of one to two percent water. The crystals settle out of the magma, and what doesn’t crystallize is the mugearite magma, which can eventually make its way to the surface as a volcanic eruption.” This happens most frequently in underground areas where molten rock comes into contact with water—places like mid-ocean rifts and volcanic islands.

The fact that Jake_M closely resembles mugearites indicates that it likely took the same path, forming after other minerals crystallized in the presence of underground water and the remaining minerals were sent to the surface. This would suggest that, at least at some time in the past, Mars contained reserves of underground water.

The analysis is part of a growing body of evidence that Mars was once home to liquid water. Last September, images taken by Curiosity showed geologic features that suggested the one-time presence of flowing water at the surface. Here on Earth, analyses of several meteorites that originated on Mars have also indicated that, at some point long ago, the planet held reserves of liquid water deep underground.

This has scientists and members of the public excited, of course, because (at least as far as we know) water is a necessity for the evolution of life. If Mars was once a water-rich planet, as Curiosity’s findings increasingly suggest, it’s possible that life may have once evolved there long ago—and there may even be organic compounds or other remnants of life waiting to be found by the rover in the future.

Analysis of Jake_M, the first rock Curiosity tested, shows that it’s unlike any rocks previously found on Mars, and probably formed after hot magma came into contact with water. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)