The Dakota Badlands Used to Host Sabertoothed Pseudo-Cat Battles

The region was once home to a plethora of catlike creatures called nimravids, and fossils show they were an especially fractious breed

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/f1/eff16020-d7c2-45d1-aca7-bf75dc03b364/img_0139.jpg)

The fossil may be one of the most tragic ever discovered. The skull, exhumed from the badlands of Nebraska, had once belonged to a cat-like animal called Nimravus brachyops. It was beautiful and nearly intact, but its jaws told a terrible story. The mammal’s elongated right canine tooth pierced the upper arm bone of another Nimravus.

Paleontologist Loren Toohey, who described the poor beast in a 1959 paper, wasn’t sure how this had happened. Perhaps, he wrote, “the piercing may be due to the weight of the overlying sediments,” which pushed the tooth through an underlying bone over time.

But there was another possibility: The punctured bone might have been an accidental injury in a fight between two pseudo-cats, Toohey speculated. He avoided mentioning the inescapable conclusion if this were true—the two carnivores would have been locked together in a deadly configuration, with one unable to eat and the other unable to walk.

Lyrical science writer Loren Eiseley was so moved by the apparent struggle he wrote the poem “The Innocent Assassins” to honor to unfortunate duo. The fierce Nimravus evolved “only to strike and strike, beget their kind, and go to strike again.” As it turns out, Eiseley was on to something. Recent research has revealed that these pseudo-cats, collectively called nimravids, were among the most fractious creatures of all time.

Paleontologists often refer to nimravids as “false sabercats,” although this appellation isn’t quite fair. It makes nimravids sound like imitators or impostors when they were sporting elongated fangs long before true cats, like the iconic sabertoothed Smilodon, which lived from 2.5 million to about 10,000 years ago. Nimravids were so slinky and cat-like that the main differences between them and true cats can only be seen in the anatomy at the back of the skull, with nimravids lacking a complete bony closure around the middle ear that true cats have.

While not nearly as famous as sabertoothed cats, nimravids had a great run. Between their heyday of 40.4 and 7.2 million years ago, their family spun off into a variety of species with sizes ranging from bobcat to lion. Some of these almost-cats lived in close proximity to each other.

In places like the White River Badlands, a rich stomping ground for mammalian paleontologists, up to five different genera of nimravids were present together between 33.3 and 30.8 million years ago. But these pseudo-cats were not always good neighbors. Working from fossils discovered over a century, North Dakota Geological Survey paleontologist Clint Boyd and his collaborators have found that nimravids were frequently at each others’ throats.

Two lucky breaks inspired the research, Boyd says. In 2010, a seven-year-old visitor to Badlands National Park happened upon a skull of the nimravid Hoplophoneus primaevus right next to a park visitor center.

“That specimen preserves an excellent series of bite marks on the skull from another nimravid,” Boyd says. Fighting nimravids stuck in his mind when he set about designing a new exhibit about the ancient predators for the Museum of Geology at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology a few years later. Boyd already knew that one of the nimravid skulls being used for the exhibit, described in 1936, also showed bite marks from one of its own kind, but other skulls he pulled for display surprised him.

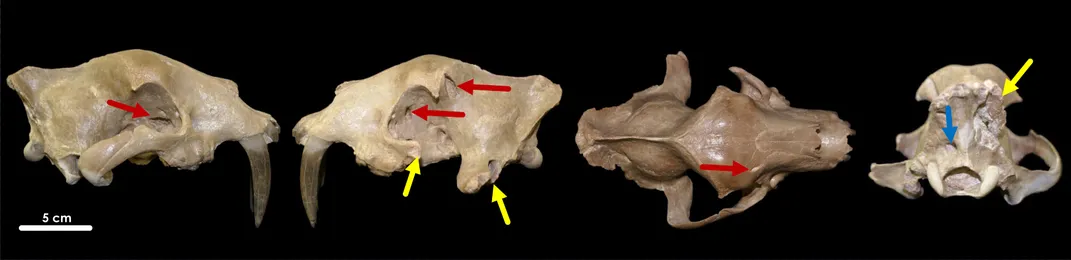

“As she was cleaning the specimens, the fossil preparator, Mindy Householder, began encountering new bite marks that had been covered over with sediment and plaster.” Boyd and his colleagues now have at least six specimens representing three nimravid species that carry signs of combat with other pseudo-sabercats.

All this bitey behavior runs counter to what was expected for predators with thin, relatively delicate saberteeth.

“The standard thought with regards to any saber-toothed animal is that the long, thin upper canines are vulnerable to breakage, and that the animals would avoid impacting hard structures like bone as much as possible,” Boyd says. A nimravid having to fight for territory or its life against another sabertooth suspended that rule—it seems the likes of Nimravus “would not shy away from using their canines to their full advantage.”

The constellation of punctures and scrapes on the various remains even hint at how Nimravus and its kind went about attacking each other.

“Punctures from the lower canines are mostly on the back of the skull, while those from the upper canines are situated around the eyes and farther forward, indicating that most attacks are coming from behind,” Boyd says.

In other words, nimravids fought dirty. The fact that most of the upper canine punctures are in or around the eye sockets, Boyd says, means “these animals were taking advantage of their elongated canines to blind their competitors.”

Boyd suspects that the fossils investigated so far aren’t the only ones to show signs of these battles. Many museums hold nimravid skulls excavated from the White River Badlands and elsewhere, and Boyd expects that some of these samples might be worth looking at for telltale injuries. Doing so requires a careful eye, however, as sediment or plaster used in reconstruction might cover the damage, which is often relatively subtle and takes a trained eye to pick out.

The realization that some saber-fanged carnivores used their impressive dental cutlery to fight each other raises questions about their behavior that have rarely been considered. Did nimravids threat-yawn to show off their canines and drive their competitors away? What made nimravids exceptionally irritable with other pseudo-sabercats? These are the mysteries liable to keep paleontologists awake at night, thinking of what Eiseley called the “perfect fury” of these long-lost predators.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)