Defending the Rhino

As demand for rhino horn soars, police and conservationists in South Africa pit technology against increasingly sophisticated poachers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rhinos-black-rhino-Kenya-631.jpg)

Johannesburg’s bustling O. R. Tambo International Airport is an easy place to get lost in a crowd, and that’s just what a 29-year-old Vietnamese man named Xuan Hoang was hoping to do one day in March last year—just lie low until he could board his flight home. The police dog sniffing the line of passengers didn’t worry him; he’d checked his baggage through to Ho Chi Minh City. But behind the scenes, police were also using X-ray scanners on luggage checked to Vietnam, believed to be the epicenter of a new war on rhinos. And when Hoang’s bag appeared on the screen, they saw the unmistakable shape of rhinoceros horns—six of them, weighing more than 35 pounds and worth up to $500,000 on the black market.

Investigators suspected the contraband might be linked to a poaching incident a few days earlier on a game farm in Limpopo Province, on South Africa’s northern border. “We have learned over time, as soon as a rhino goes down, in the next two or three days the horns will leave the country,” Col. Johan Jooste of South Africa’s national priority crime unit told me when I interviewed him in Pretoria.

The Limpopo rhinos had been killed in a “chemical poaching,” meaning that hunters, probably in a helicopter, had shot them using darts loaded with an overdose of veterinary tranquilizers.

The involvement of sophisticated criminal syndicates has soared along with the price of rhino horn, said Jooste, a short, thickly built bull of a man. “The couriers are like drug mules, specifically recruited to come into South Africa on holiday. All they know is that they need to pack for one or two days. They come in here with minimal contact details, sometimes with just a mobile phone, and they meet with guys providing the horns. They discard the phone so there’s no way to trace it to any other people.”

South African courts often require police to connect the horns to a specific poaching incident. “In the past,” said Jooste, “we needed to physically fit a horn on a skull to see if we had a match. But that was not always possible, because we didn’t have the skull, or it was cut too cleanly.”

Police sent the horns confiscated at the airport to Cindy Harper, head of the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at the University of Pretoria. Getting a match with DNA profiling had never worked in the past. Rhino horn consists of a substance like a horse’s hoof, and conventional wisdom said it did not contain the type of DNA needed for individual identifications. But Harper had recently proved otherwise. In her lab a technician applied a drill to each horn to obtain tissue samples, which were then pulverized, liquefied and analyzed in what looked like a battery of fax machines.

Two of the horns turned out to match the animals poached on the Limpopo game farm. The odds of another rhino having the same DNA sequence were one in millions, according to Harper. On a continent with only about 25,000 rhinos, that constituted foolproof evidence. A few months later, a judge sentenced Hoang to ten years in prison—the first criminal conviction using DNA fingerprinting of rhino horn.

It was a rare victory in a rapidly escalating fight to save the rhinoceros. Rhino poaching had once been epidemic in Africa, with tens of thousands of animals slaughtered and whole countries stripped of the animals, largely to obtain horns used for traditional medicines in Asia and dagger handles in the Middle East. But in the 1990s, under strong international pressure, China removed rhino horn from the list of traditional medicine ingredients approved for commercial manufacturing, and Arab countries began to promote synthetic dagger handles. At the same time, African nations bolstered their protective measures, and the combined effort seemed to reduce poaching to a tolerable minimum.

That changed in 2008, when rhino horn suddenly began to command prices beyond anyone’s wildest imagining. The prospect of instant riches has driven a global frenzy: Police in Europe have reported more than 30 thefts of rhino horn this year from museums, auction houses and antiques dealerships.

Most of the poaching takes place in South Africa, where the very system that helped build up the world’s largest rhino population is now making those same animals more vulnerable. Legal trophy hunting, supposedly under strict environmental limits, has been a key part of rhino management: The hunter pays a fee, which can be $45,000 or more to kill a white rhino. The fees give game farmers an incentive to breed rhinos and keep them on their property.

But suddenly the price of rhino horn was so high that the hunting fees became just a minor cost of doing business. Tourists from Asian nations with no history of trophy hunting began showing up for multiple hunts. And wildlife professionals began to cross the line from hunting rhinos to poaching them.

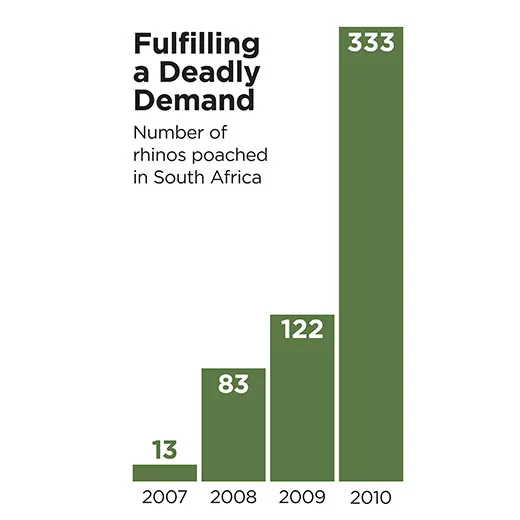

Investigators from Traffic, a group that monitors international wildlife trade, traced the sudden spike in demand to a tantalizing rumor: Rhino horn had miraculously cured a VIP in Vietnam of terminal liver cancer. In traditional Asian medicine, rhino horn is credited with relatively humble benefits such as relieving fever and lowering blood pressure—claims that medical experts have debunked. (Contrary to popular belief, rhino horn has not been regarded as an aphrodisiac.) But fighting a phantom cure proved almost impossible. “If it was a real person, we could find out what happened and maybe demystify it,” said Tom Milliken of Traffic. South Africa lost 333 rhinos last year, up from 13 in 2007. Officials estimate that 400 could be killed by the end of this year.

Scientists count three rhino species in Asia and two in Africa, white and black. (The Asian species are even more rare than the African.) Black rhinos were knocked down by the poaching crisis of the 1990s to fewer than 2,500 animals, but the population has rebuilt itself to about 4,800.

White rhinos once occurred in pockets down the length of Africa, from Morocco to the Cape of Good Hope. But because of relentless hunting and colonial land-clearing, there were no more than a few hundred individuals left in southern Africa by the end of the 19th century, and the last known breeding population was in KwaZulu-Natal Province on South Africa’s eastern coast. In 1895, colonial conservationists set aside a large tract specifically for the remaining rhinos—Africa’s first protected conservation area—now known as Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park.

The 370-square-mile park is beautiful country, said to have been a favorite hunting ground for Shaka, the 19th-century Zulu warrior king. Broad river valleys divide the rolling highlands, and dense green scarp forests darken distant slopes.

My guide in the park was Jed Bird, a 27-year-old rhino capture officer with an easygoing manner. Almost before we started early one morning, he stopped his pickup truck to check out some droppings at the side of the road. “There was a black rhino here,” he said. “Obviously a bull. You can see the vigorous scraping of the feet. Spreads the dung. Not too long ago.” He imitated a rhino’s stiff-legged kicking. “It pushes up the scent. So other animals will either follow or avoid him. They have such poor eyesight, you wonder how they find each other. This is their calling card.”

You might also wonder why they bother. The orneriness of rhinos is so proverbial that the word for a group of them is not a “herd” but a “crash.” “The first time I saw one I was a 4-year-old in this park. We were in a boat, and it charged the boat,” said Bird. “That’s how aggressive they can be.” Bird now makes his living keeping tabs on the park’s black rhinos and sometimes works by helicopter to catch them for relocation to other protected areas. “They’ll charge helicopters,” he added. “They’ll be running and then after a while, they’ll say, ‘Bugger this,’ and they’ll turn around and run toward you. You can see them actually lift off their front feet as they try to have a go at the helicopter.”

But this fierceness can be misleading. Up the road a little later, Bird pointed out some white rhinos a half-mile off, and a few black rhinos resting nearby, placid as cows in a Constable painting of the British countryside. “I’ve seen black and white rhino lying together in a wallow almost bum-to-bum,” he said. “A wallow’s like a public facility. They sort of tolerate one another.”

After a moment, he added, “The wind is good.” That is, it was blowing our scent away from them. “So we’ll get out and walk.” From behind the seat, he brought out a .375 rifle, the minimum caliber required by the park for people wandering near big unpredictable animals, and we set off into the head-high acacia.

The peculiar appeal of rhinos is that they seem to have lumbered straight out of the Age of Dinosaurs. They are massive creatures, second only to elephants among modern land animals, with folds of thick flesh that look like protective plating. A white rhino can stand six feet at the shoulders and weigh 6,000 pounds or more, with a horn up to six feet in length, and a slightly shorter one just behind. (“Rhinoceros” means “nose horn.”) Its eyes are dim little poppy seeds low on the sides of its great skull. But the big feathered ears are acutely sensitive, as are its vast snuffling nasal passages. The black rhino is smaller than the white, weighing up to about 3,000 pounds, but it’s more quarrelsome.

Both black and white rhinos are actually shades of gray; the difference betwen them has to do with diet, not skin color. White rhinos are grazers, their heads almost always down on the ground, their wide, straight mouths constantly mowing the grass. They are sometimes known as square-lipped rhinos. Black rhinos, by contrast, are browsers. They snap off low acacia branches with the chisel-like cusps of their cheek teeth and swallow them thorns and all. “Here,” Bird said, indicating a scissored-off plant. “Sometimes you’re walking and if you’re quiet, you can hear them browsing 200 or 300 meters ahead. Whoosh, whoosh.” Blacks, also known as hook-lipped rhinos, have a powerful prehensile upper lip for stripping foliage from bushes and small tree branches. The lip dips down sharply in the middle, as if the rhino had set out to grow an elephant trunk but ended up becoming Dr. Seuss’ Grinch instead.

We followed the bent grass the rhinos had trampled, crossed through a deep ravine and came out onto a clearing. The white rhinos were moving off, with tick-eating birds called oxpeckers riding on their necks. But the black rhinos had settled down for a rest. “We’ll go into those trees there, then wake them up and get them to come to us,” Bird said. My eyes widened. We headed out in the open, with nothing between the rhinos and us except a few hundred yards of low grass. Then the oxpeckers gave out their alarm call—“Chee-cheee!”—and one of the black rhinos stood up and seemed to stare straight at us. “She’s very inquisitive,” Bird said. “I train a lot of field rangers, and at this point they’re panicking, saying, ‘It’s got to see us,’ and I say, ‘Relax, it can’t see us.’ You just have to watch its ears.”

The rhino settled down and we made it to a tree with lots of knobs for hand- and foot-holds where elephants had broken off branches. Bird leaned his rifle against another tree and we climbed up. Then he started blowing out his cheeks and flapping his lips in the direction of the rhinos. When he switched to a soft high-pitched cry, like a lost child, a horn tip and two ears rose above the seed heads of the grass and swung in our direction like a periscope. The rest of the rhino soon followed, lifting up ponderously from the mud. As the first animal ambled over, Bird identified it from the pattern of notches on her ears as C450, a pregnant female. Her flanks were more blue than gray, glistening with patches of dark mud. She stopped when she was about eight feet from our perch, eyeing us sideways, curious but also skittish. Her nostrils quivered and the folds of flesh above them seemed to arch like eyebrows, inquiringly. Then suddenly her head pitched up as she caught our alien scent. She turned and ran off, huffing like a steam engine.

A few minutes later, two other black rhinos, a mother-daughter pair, came over to investigate. They nosed into our small stand of trees. Bird hadn’t figured they would come so close, but now he worried that one of them might bump into his rifle. It would have been poetic justice: Rhino shoots humans. He spared us by dropping his hat down in front of the mother to send her on her way.

Rhino pregnancies last 16 months, and a mother may tend her calf for up to four years after birth. Even so, conservation programs in recent decades have managed to produce a steady surplus of white rhinos. Conservationists hope to increase the black rhino population as a buffer against further poaching, and their model is what Hluhluwe-iMfolozi did for white rhinos beginning in the 1950s.

South Africa was then turning itself into the world leader in game capture, the tricky business of catching, transporting and releasing big, dangerous animals. White rhinos were the ultimate test—three tons of anger in a box. As the remnant Hluhluwe-iMfolozi population recovered, it became the seed stock for repopulating the species in Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and other countries. In South Africa itself, private landowners also played a key part in rhino recovery, on game farms geared either to tourism or trophy hunting. As a result there are now more than 20,000 white rhinos in the wild, and the species is no longer on the threatened list.

Building up the black rhino population today is more challenging, in part, because human populations have boomed, rapidly eating up open space. Ideas about what the animals need have also changed. Not too long ago, said Jacques Flamand of the World Wildlife Fund, conservationists thought an area of about 23 square miles—the size of Manhattan—would be enough for a founding population of a half-dozen black rhinos. But recent research says it takes 20 founders to be genetically viable, and they need about 77 square miles of land. Many rural landowners in South Africa want black rhinos for their game farms and safari lodges. But few of them control that much land, and black rhinos are far more expensive than whites, selling at wildlife auctions for about $70,000 apiece before the practice was suspended.

So Flamand has been working with KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Wildlife, the provincial park service, to cajole landowners into a novel partnership: If they agree to open up their land and meet stringent security requirements, KZN will introduce a founding population of black rhinos and split ownership of the offspring. In one case, 19 neighbors pulled down the fences dividing their properties and built a perimeter fence to thwart poachers. “Security has to be good,” said Flamand. “We need to know if the field rangers are competent, how they are equipped, how organized, how distributed, whether they are properly trained.” Over the past six years, the range for black rhinos in KwaZulu-Natal has increased by a third, all on private or community-owned land, he said, allowing the addition of 98 animals in six new populations.

Conservationists have had to think more carefully about which animals to move, and how to move them. In the past, parks sometimes transferred surplus males without bothering to include potential mates, and many died. But moving mother-calf pairs was perilous, too; more than half the calves died, according to Wayne Linklater, a wildlife biologist at New Zealand’s Victoria University and lead author of a new study on black rhino translocations. Catching pregnant females also created problems. The distress caused by capture led to some miscarriages, and the emphasis on moving numerous young females may also have depleted the literal motherlode—the breeding population protected within Hluhluwe-iMfolozi. “We were left with a whole lot of grannies in the population, and not enough breeding females,” said park ecologist David Druce.

Researchers have now come to recognize that understanding the social nature of black rhinos is the key to getting them established, and reproducing, in new habitats. A territorial bull will tolerate a number of females and some adolescent males in his neighborhood. So translocations now typically start with one bull per water source, with females and younger males released nearby. To keep territorial bulls separated during the crucial settling process, researchers have experimented with distributing rhino scent strategically around the new habitat, creating “virtual neighbors.” Using a bull’s own dung didn’t work. (They are at least bright enough, one researcher suggests, to think: “That’s my dung. But I’ve never been here before.”) It may be possible to use dung from other rhinos to mark a habitat as suitable and also convey that wandering into neighboring territories could be risky.

The release process itself has also changed. In the macho game capture culture of the past, it was like a rodeo: A lot of vehicles gathered around to watch. Then someone opened the crate and the rhino came busting out, like a bull entering an arena. Sometimes it panicked and ran till it hit a fence. Other times it charged the vehicles, often as documentary cameras rolled. “It was good for television, but not so good for animals,” said Flamand. Game capture staff now practice “soft releases.” The rhino is sedated in its crate, and all the vehicles move away. Someone administers an antidote and backs away, leaving the rhino to wander out and explore its new neighborhood at leisure. “It’s very calm. It’s boring, which is fine.”

These new rhino habitats are like safe houses, and because of the renewed threat of poaching, they are high-tech safe houses at that. Caretakers often notch an animal’s ear to make it easier to identify, implant a microchip in its horn for radio frequency identification, camera-trap it, register it in a genetic database and otherwise monitor it by every available means short of a breathalyzer.

Early this year, Somkhanda Game Reserve, an hour or so up the road from Hluhluwe-iMfolozi, installed a system that requires implanting a GPS device the size of D-cell batteries in the horn of every rhino on the property. Receivers mounted on utility poles register not just an animal’s exact location but also every movement of its head, up and down, back and forth, side to side.

A movement that deviates suspiciously from the norm causes an alarm to pop up on a screen at a security company, and the company relays the animal’s location to field rangers back at Somkhanda. “It’s a heavy capital outlay,” said Simon Morgan of Wildlife ACT, which works with conservation groups on wildlife monitoring, “but when you look at the cost of rhinos, it’s worth it. We have made it publicly known that these devices are out there. At this stage, that’s enough to make poachers go elsewhere.”

A few months after the Vietnamese courier went to prison, police conducted a series of raids in Limpopo Province. Frightened by continued rhino poaching on their land, angry farmers had tipped off investigators to a helicopter they had seen flying low over their properties. Police traced the chopper and arrested Dawie Groenewald, a former police officer, and his wife, Sariette, who operated trophy hunting safaris and ran a game farm in the area. They were charged with being kingpins in a criminal ring that profited from contraband rhino horns and also with poaching rhinos on their neighbors’ game farms. But what shocked the community was the allegation that two local veterinarians, people they had trusted to care for their animals, had been helping to kill them instead. Rising prices for rhino horn, and the prospect of instant wealth, had apparently shattered a lifetime of ethical constraints.

Conservationists were shocked, too. One of the veterinarians had been a go-between for the Groenewalds when they purchased 36 rhinos from Kruger National Park in 2009. Investigators later turned up a mass grave with 20 rhino carcasses on the Groenewald farm. Hundreds of rhinos were allegedly killed by the conspirators. Thirteen people have been charged in the case so far, and the trial is scheduled for spring of 2012. In the meantime, Groenewald has received several new permits for hunting white rhinos.

Illegal trafficking in rhino horn does not seem to be confined to a single criminal syndicate or game farm. “A lot of people are gobsmacked by how pervasive that behavior is throughout the industry,” said Traffic’s Milliken. “People are just blinded by greed—your professional hunters, your veterinarians, the people who own these game ranches. We have never seen this level of private sector complicity with gangs supplying horn to Asia.”

Like Milliken, most conservationists believe trophy hunting can be a legitimate contributor to the conservation of rhinos. But they have also seen that hunting creates a moral gray zone. The system depends on harvesting a limited number of rhinos under permits issued by the government. But when the price is right, some trophy-hunting operators apparently find they can justify killing any rhino. Obtaining permits becomes a technicality. The South African government is debating a moratorium on rhino hunting.

For Milliken, the one hopeful sign is that the price for rhino horn seems to have spiked too quickly to be attributable to increased demand alone. That is, the current crisis may be a case of the madness of crowds—an economic bubble inflated by speculative buying in Asia. If so, like other bubbles, it will eventually go bust.

In the meantime, the rhinos continue to die. At Hluhluwe-iMfolozi, poachers last year killed 3 black rhinos and 12 whites. “We have estimated that what we are losing would basically overtake the birthrate in the next two years, and populations will start to drop down,” said San-Mari Ras, a district ranger. That is, the park may no longer have any seed stock to send to other new habitats.

From the floor of her office, Ras picked up the skull of a black rhino calf with a neat little bullet hole into its brain. “They will take a rhino horn even at this size,” she said, spreading her thumb and index finger. “That’s how greedy the poachers can be.”

Richard Conniff’s latest book, The Species Seekers, comes out in paperback this month.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/richard-conniff-240.jpg)