Elephants Have Male Bonding Rituals, Too

In her new book, Caitlin O’Connell shows how the interactions of tight-knit bulls can be surprisingly similar to human relationships

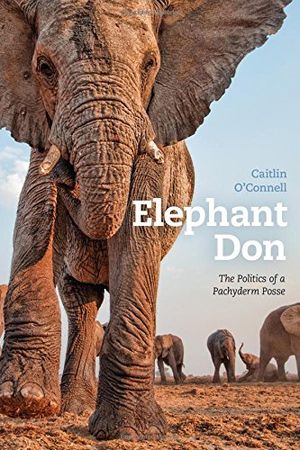

Ecologist Caitlin O’Connell has spent more than two decades observing elephants on the sandy plains of Etosha National Park, in northern Namibia. She arrives sometime in June each season, sets up camp and settles into her data collection, recording the elephants’ comings and goings, as well as their interactions, from a tower north of Mushara water hole. “The pattern of animal movements demarks the passage of time almost as reliably as the cycles of the sun and moon,” she writes in her new book, Elephant Don: The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse, out in April from University of Chicago Press.

African elephants are known for their matriarchal societies, with a dominant female leading a clan that includes her young and their offspring. Males are born into these families, and sisters, mothers and aunts care for the young elephants. As they mature into bulls, the males are kicked out of the group and sent off to fend for themselves. But they don’t become lone wanderers detached from any community, as O’Connell’s recent research at Mushara highlights. They travel together, drink together, urge one another into action and form friendships that, like human relationships, might change with the seasons or last a lifetime.

I spoke with O'Connell about elephant bonding and getting to know the Mushara posse. (The following has been edited for length.)

Why did you choose to focus your new book on male elephants?

Most people don’t realize that male elephants are very social animals. Having company is important to them. They form close bonds and have overtly ritual relationships. When a dominant male arrives on the scene, for example, you have the second-, third-, fourth-ranking bulls back up and let him into the best position at the water hole. The younger bulls will stand in line and wait to be able to place their trunks in his mouth. They are waiting with anticipation to be able to do this. In time, all of the bulls will come and greet the dominant male in the same way. It is extremely organized, like lining up to kiss the ring of a pope or a Mafioso don.

The big, older bulls are targets of poaching. People think of lone bulls out there, and they might think, “What is it going to hurt a population if you cull a few of those elephants?” But these old males are similar to matriarchs. They are repositories of knowledge, and they teach the next generation.

Are there other rituals the males follow?

You’d think that a male might show up at a water hole, and he might interact with the others and then leave. Why would he want those younger bulls to follow him to another water hole? But the dominant male will actually corral up his constituents. Even if they aren’t ready to leave, he will force the younger ones by pushing on their behinds.

And there’s a second ritual, a vocal ritual between bonded individuals. The dominant male will make the call to leave, what we call a “Let’s go” rumble, similar to what a matriarch would emit. Another male elephant, right as the first finishes, will also rumble, and then a third might rumble. And all the elephants will follow the dominant male out.

Introduce us to Greg, the dominant male at the center of your story. Why is he the one in charge?

Greg is not the biggest bull, not the oldest, and he doesn’t have the biggest tusks. He is very strong-willed and he is a great politician. He is the most felicitous and gentle dominant bull that I’ve witnessed. He actively solicits the young bulls and gets them into the fold and welcomes them. He’s also very quick to discipline someone who gets out of line in the higher ranks. It’s like he knows how to manage the carrot and the stick.

I’ve seen other bulls try to become more dominant and raise their rank, but they are so overly aggressive that other bulls don’t want them around. There’s an elephant Beckham, and he is clearly trying to become friends with a bonded pair, Keith and Willie, but he becomes so aggressive that they don’t want him to follow them.

You’ve mentioned a few other elephants now. Willie, which is short for Willie Nelson, right? And there’s a Prince Charles, a Luke Skywalker. How do you decide on the names?

We try to match the name to at least one physical feature. Willie Nelson is very raggedy. Every elephant has a catalog number, but these names help us in our practical dealings with everyday identification. There are several rock stars in the mix, because of these really long, black, scraggly tails that the elephants have. Ozzy Osbourne is another one.

And do these elephants also have different personalities?

As it turns out, Willie Nelson is a very mild, gentle fellow. All the females seem attracted to him. Another interesting character is Prince Charles, who was a very aggressive, lower-ranking bull until, at one point, Greg went missing. Before Greg went missing, younger bulls would admire Prince Charles and want to follow him and he would never let them. He would look over his shoulder, stop, turn around and give them a big head shake, like “You are not following me.” After Greg went missing, though, Prince Charles completely changed his behavior. He became much more diplomatic and much more interested in trying to get a posse of his own.

What other kinds of circumstances might shake up the hierarchy?

Social animals are thought to form dominance hierarchies to minimize conflict over access to resources, in this case, especially, water. If you don’t have limited resources, you don’t need to have such a strict linear hierarchy. In the drier years, the elephants form these big, tight-knit groups. But in the wetter years, when there are more resources, more places to drink, that hierarchy breaks down. In the wetter years, the youngsters will get a little more aggressive. They aren’t as reverent.

During these wet years, you could see times when Greg was struggling to hold his power. He would initiative a “Let’s go” rumble, and then look back and nobody has moved. This is really embarrassing. They are ignoring him. When he comes back, he has to physically coerce by shoving, by rubbing up against close associates that are lower in rank.

Do we know how long Greg’s dominance will last?

When I first started keeping track of dominance between males, Greg was clearly the dominant bull. I started asking colleagues who study other long-lived social animals, “What’s the life expectancy of the dominant individual?” It is very stressful to be up there, fighting off the others constantly and having to keep your rank. I was surprised how little information there was out there.

There is a window in which Greg is wounded, and we have never learned for sure exactly what happened. There was a slice off the side of his trunk. It was very raw. He’d have to spend double the time drinking because half of the water would fall out; there’d be this spilling noise. And, after drinking, he would soak it in the water for an hour. Nobody wanted to wait around with him. And he did not want to be with associates his age or older. If anyone approached, he would be aggressive.

But then the following year, he came back fully fit again. He wasn’t skinny. His ribs weren’t showing. He looked healthy again, and his trunk wound was not as raw. He didn’t have to soak it. He was back at the height; it was the most amazing thing. He had his posse, and all of those just underneath him in rank fell back in line. The durability of his position at the top, even with fluctuations in wet years, made me think, well, as long as he is fit, he is going to stay on top.

You have another book coming out, a novel about illegal ivory poaching. Why write fiction?

The novel [Ivory Ghosts] has been a 20-year labor of love, but it’s for a different purpose—to get people to understand what it is like for people to live with elephants on the ground, the very subtle politics of how to conserve elephants, and what’s the right way, and how do deal with the craziness of Africa. It’s about corruption and trust and how to build solidarity for the elephant.

What inspired the story was working for the Namibian government in the Caprivi region. My husband and I were scientists contracted to the Ministry of Environment and Tourism. I was so inspired by our boss and the rangers that he managed, their dedication to elephants and protecting them against poachers and putting their lives on the line at every moment that they were out on patrol. They were such colorful, dedicated characters. The book is based on a lot of experiences we had. I specifically wanted to write it as fiction to get past the idea of preaching to the choir. I wanted to be able to spread the word.