Emperor Penguin Colonies Will Suffer As Climate Changes

Scientists project that two thirds of emperor penguin colonies will drop by 50 percent in the next century

:focal(515x158:516x159)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/b5/50b53382-3637-4159-a601-22b860167cc6/42-28147134edit.jpg)

The iconic emperor penguin march across the Antarctic ice could one day be more of an isolated waddle. Cute as they may be, emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) are in for a rough patch with the impending threat of global climate change, according to predictions of an international team of scientists.

According to a study published today in Nature Climate Change, emperor penguin colonies will see a 19 percent global decline in the next century. “For a while our model predicts that the global population size is actually going to increase but by the end of the century it’s going to have decreased significantly and it’s going to be declining quite rapidly,” says Hal Caswell, a co-author and a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts and the University of Amsterdam.

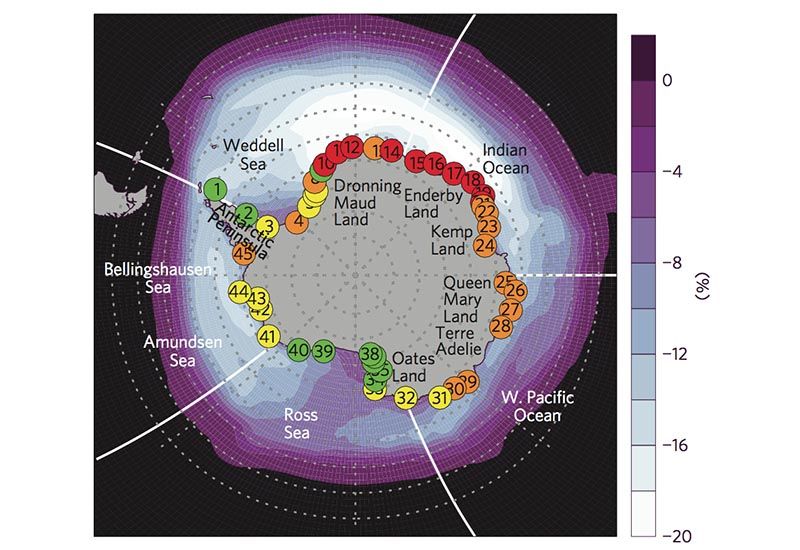

Some colonies will fare better than others. But two thirds of them are likely to drop by more than 50 percent by 2100, at which point the species will lose numbers by 3.2 percent each year, the study predicts.

The fate of emperor penguins is inextricably linked to sea ice. It's where these iconic Antarctic birds make their home, and their trek from their nests across the ice to the ocean to hunt for food is legendary.

Sea ice's impact on penguin populations depends on Goldilocks-like rules. “Its effects operate on different parts of their lifecycle in a subtle sort of way,” says Caswell. Too much sea ice makes foraging harder—parents spend a lot of energy and take longer to feed their young. Adult numbers drop, and many young don't make it past their adolescence. On the other hand, too little sea ice means less krill to eat and nowhere to hide from predators.

Since the 1960s, scientists have been learning all that they can about one emperor penguin colony at Terre Adélie, East Antarctica. According to previous studies, the colony in Terre Adélie could see an 81% population drop by 2100 due to warmer temperatures. But satellites have spotted 44 other colonies across the continent. Given that climate change varies regionally, just looking at one group doesn't provide a very informative picture of the fate of the species.

To get some specifics, Caswell and his colleagues came up with an algorithmic model that merged sea ice data with what they knew about how penguin populations change through mating, breeding, development, and other seasonal factors. From observing the colony at Terre Adélie, scientists have a pretty good idea of how penguin populations normally fluctuate from one year to another and how much those population growth rates vary. From climate change models, they extracted information about how much sea ice levels will change in the 45 colony locations across Antarctica. Thanks to the extensive Terre Adélie data, they also know how penguin colonies respond to sea ice changes. "Our models take into account both the effects of too much and too little sea ice in the colony area," explains co-author Stephanie Jenouvrier, also of WHOI. In overlaying these data sets, the researchers were able to extrapolate how each colony might fare, running thousands of simulations.

According to their results, most colonies will actually do okay until around 2050. In the Ross Sea, colonies will lose the least amount of sea ice, so they will actually increase, buffering overall population counts—that is, until around 2100, when they're projected to start dropping too. Colonies in the eastern Weddell Sea and the Western Indian Ocean will be hit hardest; they’ll see low sea ice and lots of variation in sea ice levels.

“It’s like a one-two punch,” says Caswell. It’s also consistent with what biologists are seeing in other environments that either are or will be impacted by climate change. Fluctuation, it seems, is just as important as climate extremes.

Ecological forecasting comes with a lot of ifs and maybes, though. “Predicting the future is always tricky,” admits Caswell. Both population models and climate change models come with unique uncertainties. So, the researchers tried to incorporate the whole range of possibilities into their modeling system.

For example, the Bellingshausen and the Amundsen Sea have already seen big drops in sea ice, so projections for those regions are likely less severe than what will be. In fact, one colony in that region is already totally gone—probably due to climate change.

Getting an idea of which emperor penguin colonies are in the most danger allows us to make some educated decisions regarding conservation. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering emperor penguins for protection under the Endangered Species Act. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently lists emperor penguins as “near threatened,” but given their recent results the research team urges upping the species to endangered status.

Though the IUCN considers predicted population declines when evaluating the endangered status of species, conservationists have never really encountered a situation like climate change where the thing that’s threatening the species hasn’t gone into full effect yet but has a predictable trajectory.

“Climate change is this ongoing process. We can see that at some point in the future the effects are going to build up, become really negative, and start pushing the species toward extinction,” says Caswell. “Does that mean that it should be considered endangered because we can see that coming even though it hasn’t started yet—or not?” It’s unclear how policymakers will answer that question.

Scientists are still learning how emperor penguins will deal with a changing climate. A study published earlier this week found that emperor penguins might shift their colony locations and potentially adapt to a changing climate. Either way, perhaps emperor penguins could serve as a model for how to save a species threatened by climate change before it hits bottom.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)