Everything You Wanted to Know About Dinosaur Sex

By studying dinosaurs’ closest living relatives, we are able to uncover their secret mating habits and rituals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dinosaur-sex-amargasaurus-631.jpg)

I have been sitting here with two Stegosaurus models for 20 minutes now, and I just can’t figure it out. How did these dinosaurs—bristling with spikes and plates—go about making more dinosaurs without skewering each other?

Stegosaurus has become an icon of the mystery surrounding dinosaur sex. Dinosaurs must have mated, but just how they did so has puzzled paleontologists for more than 100 years. Lacking much hard evidence, scientists have come up with all kinds of speculations: In his 1906 paper describing Tyrannosaurus rex, for instance, paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn proposed that male tyrant dinosaurs used their minuscule arms for “grasping during copulation.” Others forwarded similar notions about the function of the thumb-spikes on Iguanodon hands. These ideas eventually fell out of favor—perhaps due to embarrassment as much as anything else—but the question remained. How can we study the sex lives of animals that have been dead for millions upon millions of years?

Soft-tissue preservation is very rare, and no one has yet discovered an exquisitely preserved dinosaur with its reproductive organs intact. In terms of basic mechanics, the best way to study dinosaur sex is to look at the animals’ closest living relatives. Dinosaurs shared a common ancestor with alligators and crocodiles more than 250 million years ago, and modern birds are the living descendants of dinosaurs akin to Velociraptor. Therefore we can surmise that anatomical structures present in both birds and crocodylians were present in dinosaurs, too. The reproductive organs of both groups are generally similar. Males and females have a single opening—called the cloaca—that is a dual-use organ for sex and excretion. Male birds and crocodylians have a penis that emerges from the cloaca to deliver sperm. Dinosaur sex must have followed the “Insert Tab A into Slot B” game plan carried on by their modern-day descendants and cousins.

Beyond the likely basic anatomy, things get a bit tricky. As Robert Bakker observed in his 1986 book The Dinosaur Heresies, “sexual practices embrace not only the physical act of copulation, but all the pre-mating ritual, strutting, dancing, brawling, and the rest of it.” Hundreds of dinosaur species have been discovered (and many more have yet to be found); they lived, loved, and lost over the course of more than 150 million years. There may have been as many courtship rituals as there were species of dinosaur. In recent years, paleontologists moved out of the realm of pure speculation and begun to piece together the rich reproductive lives of some of these animals.

The first priority in studying dinosaur mating is determining which sex is which. Paleontologists have tried several approaches to this problem, searching for sex differences in size or ornamentation. Frustratingly, though, few species are represented by enough fossils to allow for this sort of study, and no instance of obvious difference between the sexes in the gross anatomy of the skeleton has gone undisputed.

A breakthrough came about six years ago, when paleontologist Mary Schweitzer discovered that the secret to the dinosaur sexes has been locked in bone all along. Just prior to laying eggs, female dinosaurs—like female birds—drew on their own bones for calcium to build eggshells. The source was a temporary type of tissue called medullary bone lining the inside of their leg bone cavities. When such tissue was discovered in the femur of a Tyrannosaurus, paleontologists knew they had a female dinosaur.

Once they knew what they were looking for, paleontologists searched for medullary bone in other species. In 2008, paleontologists Andrew Lee and Sarah Werning reported that they had found medullary bone inside the limbs of the predatory dinosaur Allosaurus and an evolutionary cousin of Iguanodon called Tenontosaurus. More females, all primed to lay eggs.

Scientists can estimate the ages of these dinosaurs by examining their bone microstructure for growth rings. The findings showed that dinosaurs began reproducing early. Some females had not yet reached fully mature body size when they started laying eggs. Other fossils showed that it was only after females began reproducing that their growth began to slow. These dinosaurs grew fast and became teen moms.

Based on what is known about dinosaur lives, this strategy made evolutionary sense. Dinosaurs grew fast—another study by Lee and a different set of colleagues found that prey species such as the hadrosaur Hypacrosaurus may have grown faster than predatory species as a kind of defense. And dinosaurs, whether prey or predator, often died young, so any dinosaur that was going to pass on its genes had to get an early start.

Teen dinosaur dating did not involve drive-in movies and nights out dancing. What they actually did has been largely the subject of inference. In his 1977 tale of a female “brontosaur” (now known as Apatosaurus), paleontologist Edwin Colbert imagined what happened when the males of the sauropod herds began to feel the itch. “Frequently two males would face each other, to nod their heads up and down or weave them back and forth through the considerable arcs,” he imagined, speculating that, “at times they would entwine their necks as they pushed against each other.” Thirty years later, paleontologist Phil Senter offered a scientific variation of this idea, suggesting that the long necks of dinosaurs like Diplodocus and Mamenchisaurus evolved as a result of the competition for mates, an example of sexual selection. Females may have preferred males with extra long necks or males may have used their necks in direct competition, although neither possibility has been directly supported. Such prominent structures could well have been used in mating displays, though. What better way for a sauropod to advertise itself to members of the opposite sex than by sticking its neck out and strutting a bit?

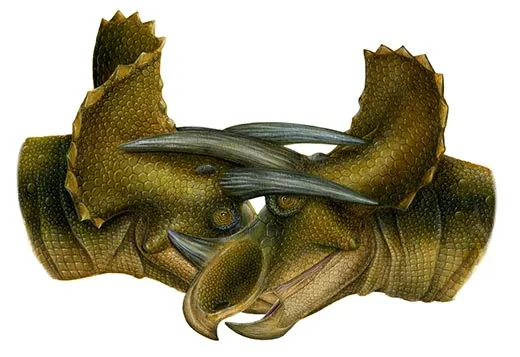

Damaged bones allow paleontologists to approach dinosaur mating habits—and their consequences—a little more closely. Painful-looking punctures on the skulls of large theropod dinosaurs such as Gorgosaurus, Sinraptor and others indicate these dinosaurs bit each other on the face during combat, according to Darren Tanke and Philip Curie. These fights were likely over mates or the territory through which prospective mates might pass. Tanke, Andrew Farke and Ewan Wolff also detected patterns of bone damage on the skulls of the horned dinosaurs Triceratops and Centrosaurus. The wounds on Triceratops, in particular, matched what Farke had predicted with models of the famous horned dinosaurs: They literally locked horns. The confrontations that left these wounds could have happened anytime, but during the mating season is the likeliest bet. Ceratopsian dinosaurs have a wide array of horn arrangements and frill shapes, and some scientists suspect these ornaments are attributable to sexual selection.

These notions are difficult to test—how can we tell whether female Styracosaurus preferred males with extra-gaudy racks of horns, or whether male Giganotosaurus duked it out with each other over mating opportunities? But an unexpected discovery gives us a rare window into how some dinosaurs courted. For decades, conventional wisdom held that we would never know what color dinosaurs were. This is no longer true. Paleontologists have found more than 20 species of dinosaurs that clearly sported feathers, and these feathers hold the secrets of dinosaur color.

Dinosaur feathers contained tiny structures called melanosomes, some of which have been preserved in microscopic detail in fossils. These structures are also seen in the plumage of living birds, and they are responsible for colors ranging from black to gray to brown to red. As long as a dinosaur specimen has well-preserved feathers, we can compare its arrangements of melanosomes with those of living birds to determine the feather’s palette, and one study last year did this for the small, feathered dinosaur Anchiornis. It looked like a modern-day woodpecker, the analysis showed: mostly black with fringes of white along the wings and a splash of red on the head.

So far only one specimen of Anchiornis has been restored in full color, but so many additional specimens have been found that paleontologists will be able to determine the variation in color within the species, specifically looking for whether there was a difference between males and females or whether the flashy red color might be mating plumage. Through the discovery of dinosaur color, we may be able to understand what was sexy to an Anchiornis.

So where does all this leave the mystery of Stegosaurus mating? With all that elaborate and pointy ornamentation, we can imagine male Stegosaurus lowering their heads and waggling their spiked tails in the air to try to intimidate each other, with the victor controlling territory and showing off his prowess. Not all females will be impressed—female choice determines ornamentation as much as competition between males does—but those that are will mate with the dominant male. All the bellowing, swaying, and posturing allows females to weed out the most fit males from the sick, weak or undesirable, and after all this romantic theater there comes the act itself.

Figuring out how Stegosaurus even could have mated is a prickly subject. Females were just as well-armored as males, and it is unlikely that males mounted the females from the back. A different technique was necessary. Perhaps they angled so that they faced belly to belly, some have guessed, or maybe, as suggested by Timothy Isles in a recent paper, males faced away from standing females and backed up (a rather tricky maneuver!). The simplest technique yet proposed is that the female lay down on her side and the male approached standing up, thereby avoiding all those plates and spikes. However the Stegosaurus pair accomplished the feat, though, it was most likely brief—only as long as was needed for the exchange of genetic material. All that energy and effort, from growing ornaments to impressing a prospective mate, just for a few fleeting moments to continue the life of the species.

Brian Switek blogs at Dinosaur Tracking and is the author of Written in Stone: Evolution, the Fossil Record, and Our Place in Nature.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)