Factory Farms May Be Ground-Zero For Drug Resistant Staph Bacteria

Staph microbes with resistance to common treatments are much more common in industrial farms than antibiotic-free operations

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130702040152Florida_chicken_house-small.jpg)

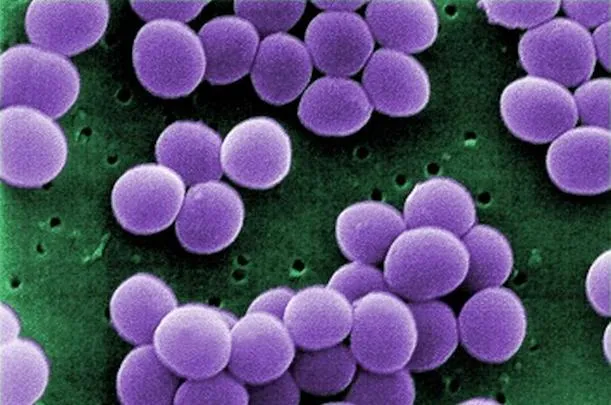

The problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria—especially MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus)—has ballooned in recent years. Bacteria in the Staphylococcus genus have always infected humans, causing skin abscesses, a weakened immune system that leaves the body more susceptible to other infections, and—if left untreated—death.

Historically, staph with resistance to drugs have mostly spread within hospitals. Last year, though, a study found that from 2003 to 2008, the number of people checking into U.S. hospitals with MRSA doubled; moreover, in each of the last three years, this number has exceeded the amount of hospital patients with HIV or influenza combined. Even worse, multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MDRSA) has become an issue, as doctors have encountered increasing numbers of patients who arrive with infections resistant to several different drugs that are normally used to treat afflictions.

It’s clear that these bacteria are acquiring resistance and spreading outside of hospital settings. But where exactly is it happening?

Many scientists believe that the problem can be traced to a setting where antibiotics are used liberally: industrial-scale livestock operations. Farm operators habitually include antibiotics in the feed and water of pigs, chickens and other animals to promote their growth rather than to treat particular infections. As a result, they expose bacteria to these chemicals on a consistent basis. Random mutations enable a small fraction of bacteria to survive, and constant exposure to antibiotics preferentially allows these hardier, mutated strains to reproduce.

From there, the bacteria can spread from the livestock to people who work in close contact with the animals, and then to other community members nearby. Previously, scientists have found MRSA living in both the pork produced by industrial-scale pig farms in Iowa and in the noses of many of the workers at the same farms.

Now, a new study makes the link between livestock raised on antibiotics and MDRSA even clearer. As published today in PLOS ONE, workers employed at factory farms that used antibiotics had MDRSA in their airways at rates double those of workers at antibiotic-free farms.

For the study, researchers from Johns Hopkins University and elsewhere examined workers at several pork and chicken farms in North Carolina. Because the workers could be at risk of losing their jobs if farm owners found out they’d participated, the researchers didn’t publish the names of the farms or workers, but surveyed them about how animals were raised at their farms and categorized them as industrial or antibiotic-free operations.

The scientists also swabbed the nasal cavities of the workers and cultured the staph bacteria they found to gauge the rates of infection by MDRSA. As a whole, the two groups of workers had similar rates of normal staph (the kind that can be wiped out by antibiotics), but colonies of MDRSA—resistant to several different drugs typically used as treatment—were present in 37 percent of workers at industrial farms, compared to 19 percent of workers at farms that didn’t use antibiotics.

Perhaps even more troubling, the industrial livestock workers were much more likely than those working at antibiotic-free operations(56 percent vs. 3 percent) to host staph that were resistant to tetracycline, a group of antibiotics prescribed frequently as well as the type of antibiotic most commonly used in livestock operations.

This research is just the beginning of a broader endeavor aimed at understanding how common agricultural practices are contributing to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The scientists say that surveying the family members of farm workers and other people they come in frequent contact with would help to model how such infections spread from person to person. Eventually, further evidence on MDRSA evolving in this setting could help justify tighter regulations on habitual antibiotic use on livestock.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)