For the First Time in 35 Years, A New Carnivorous Mammal Species is Discovered in the Americas

The Olinguito, a small South American animal, has evaded the scientific community for all of modern history

For all of modern history, a small, carnivorous South American mammal in the raccoon family has evaded the scientific community. Untold thousands of these red, furry creatures scampered through the trees of the Andean cloud forests, but they did so at night, hidden by dense fog. Nearly two dozen preserved samples—mostly skulls or furs— were mislabeled in museum collections across the United States. There’s even evidence that one individual lived in several American zoos during the 1960s—its keepers were mystified as to why it refused to breed with its peers.

Now, the discovery of the olinguito has solved the mystery. At an announcement today in Washington, D.C., Kristofer Helgen, curator of mammals at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, presented anatomical and DNA evidence that establish the olinguito (pronounced oh-lin-GHEE-toe) as a living species distinct from other known olingos, carnivorous tree-dwelling mammals native to Central and South America. His team’s work, also published today in the journal ZooKeys, represents the first discovery of a new carnivorous mammal species in the American continents in more than three decades.

Although new species of insects and amphibians are discovered fairly regularly, new mammals are rare, and new carnivorous mammals especially rare. The last new carnivorous mammal, a mongoose-like creature native to Madagascar, was uncovered in 2010. The most recent such find in the Western Hemisphere, the Colombian weasel, occurred in 1978. “To find a new carnivore species is a huge event,” said Ricardo Sampaio, a biologist at the National Institute of Amazonian Research in Brazil, who studies South American mammals in the wild and was not involved in the project.

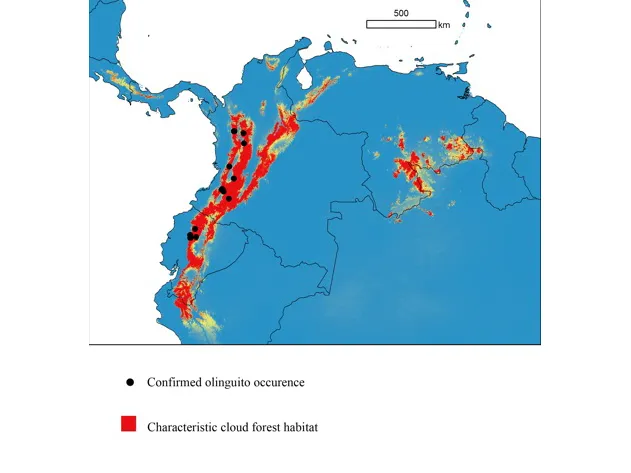

Olinguitos, formally known as Bassaricyon neblina, inhabit the cloud forests of Ecuador and Colombia in the thousands, and the team’s analysis suggests that they are distributed widely enough to exist as four separate subspecies. “This is extremely unusual in carnivores,” Helgen said, in advance of the announcement. “I honestly think that this could be the last time in history that we will turn up this kind of situation—both a new carnivore, and one that's widespread enough to have multiple kinds.”

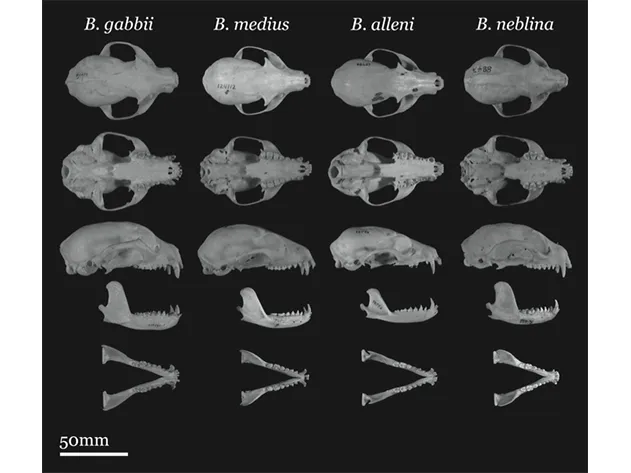

Though Helgen has uncovered dozens of unknown mammal species during previous expeditions, in this case, he did not set out to find a new species. Rather, he sought to fully describe the known olingos. But when he began his study in 2003, examining preserved museum specimens, he realized how little scientists knew about olingo diversity. “At the Chicago Field Museum, I pulled out a drawer, and there were these stunning, reddish-brown long-furred skins,” he said. “They stopped me in my tracks—they weren't like any olingo that had been seen or described anywhere.” The known species of olingo have short, gray fur. Analyzing the teeth and general anatomy of the associated skulls further hinted that the samples might represent a new species. Helgen continued his project with a new goal: Meticulously cataloguing and examining the world’s olingo specimens to determine whether samples from a different species might be hidden among them.

Visits to 18 different museum collections and the examination of roughly 95 percent of the world’s olingo specimens turned up dozens of samples that could have come from the mystery species. Records indicated that these specimens—mostly collected in the early 20th century—had been found at elevations of 5,000 to 9,000 feet above sea level in the Northern Andes, much higher than other olingos are known to inhabit.

To visit these biologically rich, moist, high-elevation forests, often called cloud forests, Helgen teamed with biologist Roland Kays of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and C. Miguel Pinto, a mammalogist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and a native of Quito, Ecuador. They traveled to Ecuadors’ Otonga Reserve, on the western slope of the Andes in 2006. “Mammalogists had worked there before and done surveys, but it seemed they'd missed this particular species,” Kays said. “The very first night there, we discovered why this might've been: When you go out and shine your light up into the trees, you basically just see clouds."

After hours of careful watch, the researchers did spot some creatures resembling the mystery specimens. But they also looked a bit like kinkajous, other small carnivorous mammals in the raccoon family. Ultimately, the researchers worked with a local hunter to shoot and retrieve one of the animals, a last-resort move among field biologists. Its resemblance to the mysterious museum specimens was unmistakable. “I was filled with disbelief,” Helgen said. “This journey, which started with some skins and skulls in an American museum, had taken me to a point where I was standing in a cloudy, wet rainforest and seeing a very real animal.”

The team spent parts of the next few years visiting the Otonga Reserve and other cloud forests in Ecuador and Colombia, studying the characteristics and behavior of the creatures that the researchers began to call olinguitos (adding the Spanish suffix “-ito” to olingo, because of the smaller size). Like other olingo species, the olinguitos were mostly active at night, but they were slightly smaller: on average, 14 inches long and two pounds in weight, compared to 16 inches and 2.4 pounds. Though they occasionally ate insects, they largely fed on tree fruit. Adept at jumping and climbing, the animals seldom descended from the trees, and they gave birth to one baby at a time.

With blood samples taken from the olinguitos and several other olingos, the researchers also performed DNA analysis, finding that the animals are far more genetically distinct than first imagined. Though other olingos lived as little as three miles away, olinguitos shared only about 90 percent of their DNA with these olingos (humans share about 99 percent of our DNA with both chimps and bonobos).

The DNA analysis also exposed the olinguito that had been hiding in plain sight. When the researchers tried to compare the fresh olinguito DNA with the only olingo DNA sample in GenBank, the National Institute of Health’s library of genetic sequences, they found that the two samples were virtually identical. Digging into the documentation of the donor animal, which had been captured by a Colombian dealer, the researchers found out that its keepers couldn’t figure out why it looked different and refused to breed with other olingos. The animal was not an olingo, but an olinguito.

Many experts believe still more unknown species may be hiding in scientific collections—perhaps even in the Field Museum collection that set Helgen’s quest in motion, specimens from Colombia mostly gathered by mammalogist Philip Hershkovitz during the 1950s. “The scientific secrets of the collections he made more than 50 years ago are still not exhausted after all this time,” said Bruce Patterson, curator of mammals at the Field Museum, noting that two new subspecies of woolly monkey were identified earlier this year based on the collection.

Helgen, Kays and the other researchers will continue studying the behavior of the olinguitos and attempt to assess their conservation status. An analysis of suitable habitats suggests that an estimated 42 percent of the animal’s potential range has already been deforested. Though the species isn’t imminently at risk, “there is reason to be concerned,” Helgen said. “A lot of the cloud forests have already been cleared for agriculture, whether for food or illicit drug crops, as well as expanding just human populations and urbanization.” If current rates continue, the animal—along with many other species endemic to these environments—could become endangered.

The researchers, though, want the olinguito to help reverse this process. “We hope that by getting people excited about a new and charismatic animal, we can call attention to these cloud forest habitats,” Helgen said. Solving other mysteries of the natural world requires leaving these habitats intact. “The discovery of the olinguito shows us that the world is not yet completely explored, its most basic secrets not yet revealed.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)