Four Months After a Concussion, Your Brain Still Looks Different Than Before

Researchers have found neurological abnormalities that persist long after the symptoms of a concussion have faded away

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131120030139brain-scan-copy.jpg)

About a month ago, I suffered my first-ever concussion, when I was (accidentally) kicked in the head playing ultimate frisbee. Over the next few weeks, I dutifully followed medical instructions to avoid intense physical activity. For a little while, I noticed a bit of mental fogginess—I had trouble remembering words and staying focused—but eventually, these symptoms faded away, and I now feel essentially the same as before.

Except, it turns out, that if doctors were to look inside my head using a type of brain scanning technology called diffusion MRI, there’s a good chance that they’d notice lingering abnormalities in the gray matter of my left prefrontal cortex. These abnormalities, in fact, could persist up to four months after the injury, even after my behavioral symptoms are long gone. This news, from a study published today in the journal Neurology, underlines just how much more prolonged and complex the healing process from even a mild concussion is than we’ve previously thought.

“These results suggest that there are potentially two different modes of recovery for concussion, with the memory, thinking and behavioral symptoms improving more quickly than the physiological injuries in the brain,” Andrew R. Mayer, a neuroscientist at the University of New Mexico and lead author of the study, explained in a press statement issued with the paper.

The abnormalities that Mayer’s team detected, they say, are so subtle that they can’t be detected by standard MRI or CT scans. Instead, they found them using the diffusion MRI technology, which measures the movement of molecules (mostly water) through different areas of the brain, reflecting the tissue’s underlying architecture and structure.

Mayer and colleagues performed these scans on 26 people who’d suffered mild concussions four months earlier, in addition to scanning them 14 days after the injuries. They also gave them behavioral and memory tests at both times, and then compared all the results to 26 healthy participants.

In the initial round, the people with concussions performed slightly worse than the healthy participants on tests that measure memory and attention, consistent with prior findings on concussions. Using the diffusion MRI, the researchers also found structural changes in the prefrontal cortex of both hemispheres of the subjects with recent concussions.

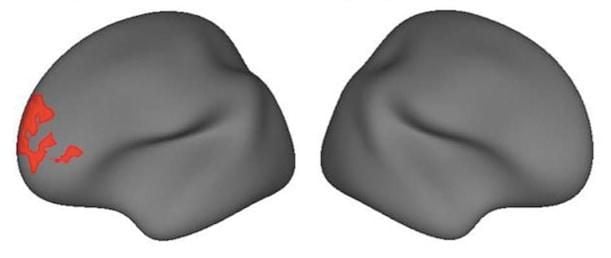

Four months later, the behavioral tests showed that the gap between the two groups had significantly narrowed, and the concussion patients’ self-reported symptoms were less significant too. But interestingly, when they averaged the scans of all 26 people, the neurological changes were still detectable in the left hemisphere of their brains.

What were these abnormalities? Specifically, their gray matter—the squishy outer layer of brain tissue in the cortex—showed ten percent more fractional anisotrophy (FA) than the controls’. This value is a measure of how likely water molecules located in this area are to travel in one direction, along the same axis, rather than scattering in all directions. It’s believed to reflect the density and thickness of neurons: the thicker and denser these brain cells are, the more likely water molecules are to flow in the direction of the cells’ fibers.

In other words, in this one particular area of the brain, people who’d suffered concussions four months earlier may have denser, thicker neurons than before. But it’s hard to say what these abnormalities reflect, and if they’re even a bad thing. As I found during my semi-obsessive post-concussion research, there are bigger gaps in scientists’ understanding of the brain than any other part of our bodies, and knowledge of the healing process after a concussion is no exception.

The scientists speculate that the increased FA could be a lingering effect of edema (the accumulation of fluid with the brain as a result of concussion) or gliosis (a change in the shape of the brain’s structural cells, rather than neurons).

But it’s even possible that this increased FA could be a sign of healing. A 2012 study found that in people who’d suffered mild concussions, higher FA scores right after the injury were correlated with fewer post-concussive symptoms, such as memory loss, a year after the injury. Similarly, a study published this past summer found a correlation between low FA scores and the incidence of severe symptoms right after a concussion. Interestingly, the researchers noted similar correlations in studies of Alzheimer’s—people with the disease tend to also demonstrate lower FA scores, in the same areas of the brain as those with most severe concussions, underscoring the link to memory performance.

If that’s the case, then the thicker, denser neurons in the brain of people with concussions might be something like the tough scabs that form after your skin gets burned, scabs that linger long after the pain has dissipated. As Mayer points out, during the recovery process after a burn “reported symptoms like pain are greatly reduced before the body is finished healing, when the tissue scabs.” In a similar way, the symptoms of a concussion—memory loss and difficulty maintaining attention, for instance—may disappear after a few weeks, while the nerve tissue continues forming its own type of scab four months later.

It’s possible that this scab, though, might be vulnerable. Scientific research is increasingly revealing just how devastating the impact of repeated concussions—the type suffered by football players—can be in the long term. “These findings may have important implications about when it is truly safe to resume physical activities that could produce a second concussion, potentially further injuring an already vulnerable brain,” Mayer said. The fact that the brain’s healing process is more prolonged than previously assumed could help explain why returning to the field a few weeks after a concussion and experiencing another is so dangerous.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)