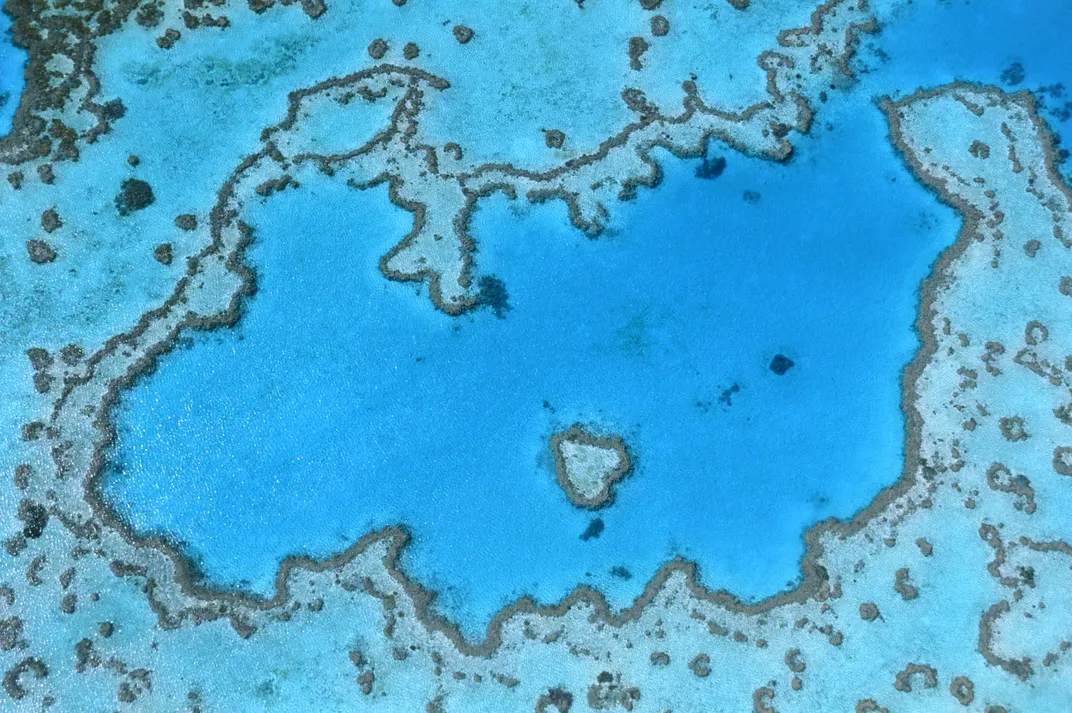

Great Barrier Reef Gets A Little Good News

New research shows that some corals may be able to adapt to faster warming than previously thought

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/10/ac106077-c030-42ab-b745-7b1ccc4e9376/42-27697031.jpg)

For coral reefs, climate change brings a triple whammy of danger: Increasing acidity makes it more difficult—and eventually impossible—for corals to form their hard structures. Rising sea levels may put some corals at depths too deep for photosynthesis. And warmer waters can cause coral bleaching—when the sea temperature rises just a degree Celsius above the summer average, the corals start to expel their symbiotic algae.

With such threats, there is great concern that the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest living system, may be doomed. But new research, published today in Nature Communications, indicates that part of Australia’s magnificent reef rapidly adapted to wildly fluctuating climates within the last 20,000 years. That could indicate the reef has a greater potential for resilience to temperature change than previously thought.

The 2,575-kilometer-long Great Barrier Reef has existed in one form or another for at least half a million years. Because new coral builds on old, dead corals, a rocky reef can be comprised of the skeletons of thousands of years’ worth of creatures. And similar to how an ice core can hold a record of what was in the ancient atmosphere, those skeletons can hold a record of the characteristics of ancient oceans.

In 2010, scientists with the International Ocean Discovery Program drilled into two sites along the seaward side of the Great Barrier Reef, collecting long cores of fossil Isopora palifera and I. cuneata corals. Thomas Felis of the University of Bremen in Germany and colleagues then determined the age of the cores through uranium-thorium dating. That showed the cores covered a time period of 12,000 to 25,000 years ago—encompassing both the peak and the end of Earth’s last ice age.

The researchers then looked at ratios of two other elements, strontium and calcium, to determine the water temperatures that the corals had grown in thousands of years ago. This ratio changes in response to temperature because a coral will absorb less strontium in warmer waters. From this analysis, Felis and colleagues could see different patterns of temperature at the two drilling sites.

Today, water temperatures at the two sites differ by only 0.6 degrees Celsius (1 degree Fahrenheit). Water at the northerly location is 26.6 degrees C; just three degrees of latitude south, sea temperature is 26.0 degrees C. But from 20,000 to 13,000 years ago, the two sites were separated by two to three degrees C in water temperature, the cores revealed.

The southern site was probably colder during that time, the researchers concluded, because of a weaker East Australian Current. Similar to the Gulf Stream off the east coast of North America, that current brings warm water from the equatorial region toward the pole. That weakening allowed cooler, subtropical waters to intrude, cooling the waters at the southern site. But when the East Australian Current sped up, it again brought tropical waters from the north, warming the southern site faster than the northern one.

“Our findings indicate that the [Great Barrier Reef] experienced substantial and regionally differing temperature change during the last deglaciation, much larger temperature changes than previously recognized,” the researchers write.

Corals are well adapted only to the sites where they live. Those in warmer locations can tolerate temperatures at which those from colder spots would bleach. That’s had scientists wondering about the corals’ potential to adapt to the warmer waters that climate change is and will be causing. This new study shows that some corals were able to adapt to a warming ocean in just a few thousand years. That provides some hope that they may be able to continue to adapt as the ocean continues to warm.

But the corals thousands of years ago were starting at lower temperatures than today—will they be able to handle even greater warming? And climate change is happening faster than past environmental change—will corals be able to adapt fast enough? Will the corals also be able to survive sea level rise and ocean acidification? And will the human race do anything to stem the rise in greenhouse gases that lie behind all these dangers?

When it comes to climate change, there are so many unknowns about how we and the natural world will act and react that it makes such predictions nigh impossible. But given the dire outlook for many of the world’s ecosystems under changing climates, any bit of good news is welcome.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)