Here’s How U.S. Groundwater Travels the Globe Via Food

Major aquifers are being drained for agricultural use, which means the water moves around in some surprising ways

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/6c/436cbf22-491e-4f89-be03-ea06015931e4/istock_000006552865_large.jpg)

Freshwater in the United States is really on the move. Much of the water pulled from underground reservoirs called aquifers gets incorporated into crops and other foodstuffs, which are then are shuttled around the country or transferred as far away as Israel and Japan, according to a new study.

The majority of water from U.S. aquifers stays within the country, but the current intense use of groundwater for agriculture is putting the nation at risk, scientists warn, because this water needs to be saved for emergencies. California, for instance, is now several years into its drought and has had to increasingly rely on groundwater to irrigate farm fields.

“By unsustainably using these aquifers, we are trading off future food security with current food production,” says study coauthor Megan Konar of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Under an uncertain climate future, in which there are more droughts, these groundwater resources will become more valuable for food production.”

Aquifers form in certain spots beneath the Earth where water pools in layers of rock, sand or gravel. This groundwater is recharged as rain or snowmelt slowly percolates from the surface. In many places, though, people are drawing more water out of aquifers than the amount that trickles in. Nearly a third of the world’s major aquifers are now losing water, a separate team of researchers reported earlier this month.

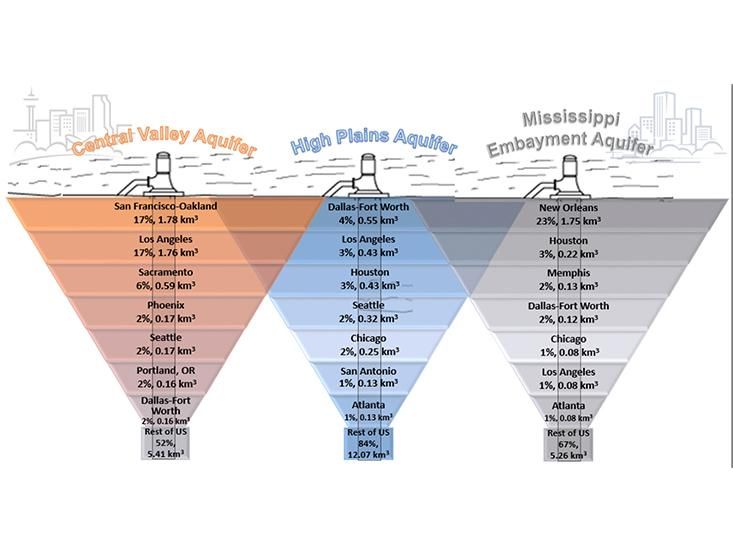

In the U.S., about 42 percent of irrigated agriculture depends on groundwater, and the depletion of our major aquifers will affect not only future food production but also urban areas that need freshwater from these sources. To better understand the risks, Konar and her colleagues focused on the agricultural use of water from three major aquifers—the Central Valley in California, the High Plains beneath the central United States and the Mississippi Embayment, which flows beneath the lower Mississippi from the tip of Illinois to Louisiana. Some 93 percent of U.S. groundwater lost since 2000 can be traced to these three aquifers.

The team gathered government data on agricultural production and the movement of food products along with data from U.S. ports, to see where food went outside the country. That let them trace “virtual groundwater” from its source beneath the Earth to its final destination on someone’s plate.

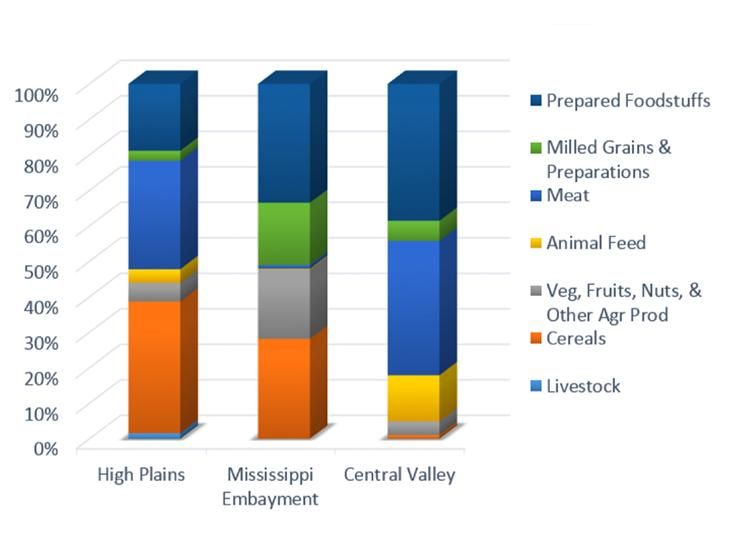

Despite the Central Valley’s reputation for fresh veggies, much of the aquifer water used in agriculture goes to the production of meat and prepared foods, the team reports this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Some 38 percent of the Central Valley’s virtual groundwater and 31 percent of the High Plains’ goes to meat, mostly beef. Meanwhile, significant portions of water from the High Plains and Mississippi Embayment go into the production of cereal crops such as wheat, rice and corn. Those crops provide not only 18.5 percent of the U.S. cereal supply but also large fractions of the supplies in Japan, Taiwan and Panama.

Overall, about 91 percent of the water stays within the United States, though it sometimes takes a fairly long journey through the food system. About 2 percent of the virtual groundwater from the Central Valley ends up in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, for instance. And 3 percent of the water from the High Plains is transferred to Los Angeles.

Unlike the Colorado River, these aquifers are not subject to any sort of sharing agreements, but policy makers may want to consider changing this, says Konar. “These aquifers are critical to domestic food security and trade interests,” she says. “Decision makers may want to reconsider current measures that exacerbate common pool aquifer depletion and instead explore opportunities to value these aquifers for their risk mitigation potential under an uncertain future.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)