Here’s How You Squeeze the Biggest Dinosaur Into a New York City Museum

A team of specialists had to get creative to mount a towering Titanosaur inside the American Museum of Natural History

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/08/7f08ade3-f002-4a03-bc29-9aa395463037/titan-lead.jpg)

For as long as paleontologists have known about dinosaurs, there’s been a friendly contest to discover the biggest. Brachiosaurus, Supersaurus, “Seismosaurus,” “Brontosaurus”—the title of “Largest Dinosaur Ever” has shifted from species to species over the last century and a half.

Now, the current contender for the superlative has stomped into view at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

The dinosaur doesn’t have an official name yet. For now, it is simply being called The Titanosaur, an enigmatic member of a group of long-necked, herbivorous behemoths. This particular animal has been making headlines since the initial discovery of its bones in 2014, which hinted that the species would be a record-breaker.

While the scientific details of the find still await publication, one thing is for sure: The Titanosaur is the largest prehistoric creature ever put on display. From its squared-off snout to the tip of its tail, the dinosaur stretches 122 feet, so long that it has to peek its tiny head out of the exhibit hall to fit in the museum.

Excavated from 100-million-year-old rock in Patagonia, the original bones were found in a jumble, with no single complete skeleton. That means the towering figure represents the intersection of old bones and new reconstruction techniques, melding casts from pieces of the new sauropod species with those of close relatives to re-create the closest estimate of the animal’s size.

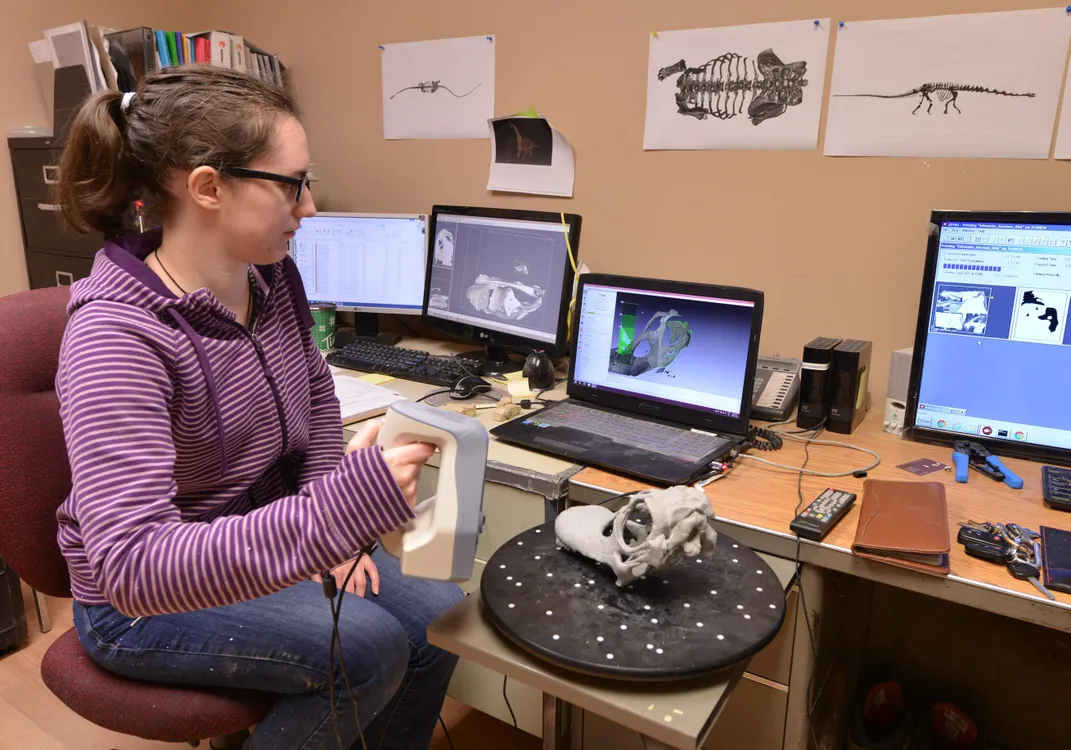

Research Casting International of Trenton, Ontario, took up the task of bringing the Cretaceous dinosaur to life. The work started before The Titanosaur was even fully out of the rock. In February 2015, the reconstruction team visited the dinosaur’s bones to digitally scan the prepared, cleaned halves of the fossils, says RCI president Peter May. They returned in May to scan the other sides, totaling over 200 bones from six individuals of the herbivorous giant.

These scans formed the basis for urethane foam molds, which were used to create fiberglass casts of each available element. May and his team then turned to the bones of other titanosaur species to fill in the missing parts.

The team made a cast for the Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio in Trelew, Argentina, near where the bones were found. “The space in Trelew is much larger, and the skeleton fit with no problems,” May says. But the American Museum of Natural History, already stuffed with fossils, was not so graciously spacious.

The only place that fit the bill was an exhibit hall on the fourth floor previously inhabited by a juvenile Barosaurus—another long-necked sauropod dinosaur—which was removed so that The Titanosaur could be crammed inside.

Erecting an animal of such size is no mean task, particularly since May says the weight of the fiberglass casts start to approach the heft of the original, fossilized elements of the dinosaur. To avoid stringing cables from the ceiling, turning the dinosaur into a biological suspension bridge, the elongated neck and tail had to be supported by a strong, hidden internal framework made from a substantial amount of steel—just imagine the muscle power the live dinosaurs would have required to keep these appendages aloft!

Altogether, it took a team of four to six people making the casts and three to ten people mounting the skeleton a total of three and a half months to re-create the dinosaur, May says. Given that these dinosaurs would have taken more than 30 years to go from a hatchling to such imposing size, the RCI team surely set a speed record for producing what may be the largest animal to have ever walked the Earth.

May himself came down from Ontario to see the grand unveiling in New York City, and he notes that the sheer size of the dinosaur can only be truly appreciated when standing right beneath it.

“This is such a huge animal that the smaller sauropods on exhibit pale in comparison,” May says. “The femur alone is eight feet long.”

How some dinosaurs managed to live at such a scale is something that still fires the imagination. “It makes you wonder how these animals moved at all, how much would have had to eat!” May says.

Whether The Titanosaur will hold on to its title is an open question. In the past, dinosaurs touted as the biggest of all time have either shrunk with better estimations or been surpassed by creatures just a little bit bigger. The current best estimates for the Patagonian goliath put it at about 10 to 15 feet longer than its nearest competitor, a titanosaur species called Futalognkosaurus on display at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, making this a true neck-in-neck race.

No matter what, though, The Titanosaur will always be among the rare things in nature that can make us feel small, perhaps letting us approach the visceral reactions our own mammalian ancestors must have had when they lived in a world dominated by such giants.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)