Hippo Haven

An idealistic married couple defy poachers and police in strife-torn Zimbabwe to protect a threatened herd of placid pachyderms

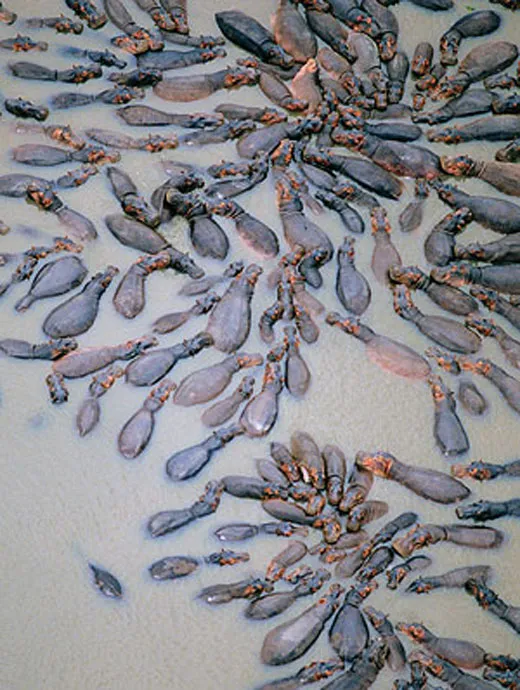

We hear the hippos before we see them, grunting, wheezing, honking and emitting a characteristic laugh-like sound, a booming humph humph humph that shakes the leaves. Turning a corner we see the pod, 23 strong, almost submerged in the muddy stream.

The dominant bull, all 6,000 pounds of him, swings around to face us. Hippos have poor eyesight but an excellent sense of smell, and he’s caught our scent. Karen Paolillo, an Englishwoman who has spent 15 years protecting this group of hippos in Zimbabwe, calls out to ease the animals’ alarm: “Hello, Robin. Hello, Surprise. Hello, Storm.”

She is most worried about Blackface, a cantankerous female guarding an 8- month-old calf that is nuzzled against her at the edge of the huddle. Blackface bares her enormous teeth, and Paolillo tenses. “She hates people, and she’s charged me plenty of times,” she says in a soft voice. “If she charges, you won’t get much warning, so get up the nearest tree as fast as you can.”

Paolillo, 50, lives on a wildlife conservancy 280 miles southeast of Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital. At one million acres, the Savé Valley Conservancy is Africa’s largest private wildlife park. But it’s no refuge from the political chaos that has gripped Zimbabwe for the past five years. Allies of Zimbabwe’s president, Robert Mugabe, have taken over 36,000 acres near where Karen and her husband, Jean-Roger Paolillo, live and threatened to burn their house down. And Jean has been charged with murder.

Karen, who is fair-haired and delicate, came by her love of animals naturally: she was born on the outskirts of London to a veterinarian father and a mother who ran a children’s zoo. In 1975, she abandoned a career in journalism to train as a casino croupier, a trade that would allow her to travel the world. In Zimbabwe, she became a safari guide. She married Jean, a French geologist, in 1988, and joined him when he took a job with a mining company searching for gold. They found none. But when Karen learned that poachers were killing hippos near their base camp, she vowed to help the animals. She and Jean leased eight acres in Savé Valley, where they watch over the last of the Turgwe River’s 23 hippos. She knows each hippo’s temperament, social status, family history and grudges.

Robin, the dominant male, edges toward Blackface and her calf, which Karen calls “Five.” The big female lunges at him, sending plumes of water into the air and chasing him away. “Blackface is a very good mother and takes special care of her calves,” Paolillo says.

On the other side of the stream, Tacha, a young female, edges toward Storm, an 8-year-old male that Robin tolerates as long as he remains subservient. Tacha dips her face in front of Storm and begins to blow bubbles through the water, a hippo flirtation. “She’s signaling to Storm that she wants to mate with him,” whispers Paolillo. “It could mean trouble, because that’s Robin’s privilege.”

Storm faces Tacha and lowers his mouth into the water, letting Tacha know that he welcomes her advances. But Blackface maneuvers her own body between the young lovers and pushes Storm, who happens to be her grandson, to the back of the huddle. “She’s protecting him from Robin’s anger because he’d attack Storm and could kill him if he tried to mate with Tacha,” Paolillo says. As if to assert his dominance, Robin immediately mounts Tacha and mates with her.

To many, the hippo is a comical creature. In the Walt Disney cartoon Fantasia, a troupe of hippo ballerinas in tiny tutus performs gravity-defying classical dance with lecherous male alligators. But many Africans regard hippos as the continent’s most dangerous animal. Although accurate numbers are hard to come by, lore has it that hippos kill more people each year than lions, elephants, leopards, buffaloes and rhinos combined.

Hippo pods are led by dominant males, which can weigh 6,000 pounds or more. Females and most other males weigh between 3,500 and 4,500 pounds, and all live about 40 years. Bachelor males graze alone, not strong enough to defend a harem, which can include as many as 20 females. A hippopotamus (the Greek word means “river horse”) spends most of the day in the water dozing. At night hippos emerge and eat from 50 to 100 pounds of vegetation. Hippos can be testy and brutal when it comes to defending their territory and their young. Though they occasionally spar with crocodiles, a growing number of skirmishes are with humans. Hippos have trampled or gored people who strayed too near, dragged them into lakes, tipped over their boats, and bitten off their heads.

Because hippos live in fresh water, they are “in the cross hairs of conflict,” says biologist Rebecca Lewison, head of the World Conservation Union’s hippo research group. “Fresh water is probably the most valuable and limited resource in Africa.” Agricultural irrigation systems and other development have depleted hippos’—and other animals’—wetland, river and lake habitats. And the expansion of waterside farms, which hippos often raid, has increased the risk that the animals will tangle with people.

In countries beset by civil unrest, where people are hungry and desperate, hippos are poached for their meat; one hippo yields about a ton of it. Some are killed for their tusk-like teeth, which can grow up to a foot or longer. (Though smaller than elephant tusks, hippo tusks don’t yellow with age. One of George Washington’s sets of false teeth was carved from hippo ivory.)

Hippos once roamed over most of Africa except the Sahara. Today they can be found in 29 African countries. (The extremely rare pygmy hippopotamus, a related species, is found in only a few West African forests.) A decade ago there were about 160,000 hippos in Africa, but the population has dwindled to between 125,000 and 148,000 today, according to the World Conservation Union. The United Nations is about to list the hippopotamus as a “vulnerable” species.

The most dramatic losses have been reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where civil war and militia rampages, with subsequent disease and starvation, have killed an estimated three million people in the past decade. Hippos are reportedly being killed by local militia, poachers, government soldiers and Hutu refugees who fled neighboring Rwanda after participating in the 1994 genocide of Tutsis. In 1974, it was estimated that about 29,000 hippos lived in DRC’s Virunga National Park. An aerial survey conducted this past August by the Congolese Institute for the Conservation of Nature found only 887 remaining.

The hippo has long fascinated me as one of nature’s most misunderstood, even paradoxical, creatures: a terrestrial mammal that spends most of its time in water, a two-ton mass that can sprint faster than a person, a seemingly placid oaf that guards its family with fierce cunning. So I went to Kenya, where a stable government has taken pains to protect the animal, to see large numbers of hippos up close. I went to Zimbabwe, in contrast, to get a feel for the impact of civil strife on this extraordinary animal.

Because Zimbabwe rarely grants visas to foreign journalists, I traveled there as a tourist and did my reporting without government permission. I entered through Bulawayo, a southern city in the homeland of the Ndebele tribe. The Ndebele people are traditional rivals of the Shona, Mugabe’s tribe. Most street life in Africa is boisterous, but the streets of Bulawayo are subdued, the result of Mugabe’s recent crackdown. People walk with heads down, as if trying not to attract attention. At gas stations cars line up for fuel, sometimes for weeks.

Zimbabwe is in trouble. It suffers 70 percent unemployment, mass poverty, annual inflation as high as 600 percent and widespread hunger. Over the past ten years, life expectancy has dropped from 63 to 39 years of age, largely due to AIDS (one quarter of the population is infected with HIV) and malnutrition. Mugabe, a Marxist, has ruled the country since it gained independence from Britain in 1980, following 20 years of guerrilla war to overthrow Ian Smith’s white-led government of what was then called Rhodesia. According to Amnesty International, Mugabe has rigged elections to stay in power, and he has jailed, tortured and murdered opponents. Since March 2005, when Mugabe and his ZANU-PF party won a national election described by Amnesty International as taking place in a “climate of intimidation and harassment,” conditions have deteriorated markedly in those parts of the country that voted for Mugabe’s opponents. His “Youth Brigades”—young thugs outfitted as paramilitary groups—have destroyed streetmarkets and bulldozed squatter camps in a campaign Mugabe named Operation Murambatsvina, a Shona term meaning “drive out the rubbish.” AU.N. report estimates that the campaign has left 700,000 of the country’s 13 million people jobless, homeless or both.

In 2000, Zimbabwe was Africa’s second most robust economy after South Africa, but then Mugabe began appropriating farmland and giving it to friends and veterans of the 1970s guerrilla wars. Most of the new landowners—including the justice minister, Patrick Chinamasa, who grabbed two farms—had no experience in large-scale farming, and so most farms have fallen fallow or are used for subsistence living.

At the Savé Valley Conservancy, originally formed in 1991 as a sanctuary for black rhinos, people belonging to the clan of a veteran named Robert Mamungaere are squatting on undeveloped land in and around the conservancy. They have cleared forests and built huts and fences. They’ve started killing wild animals. And they mean business.

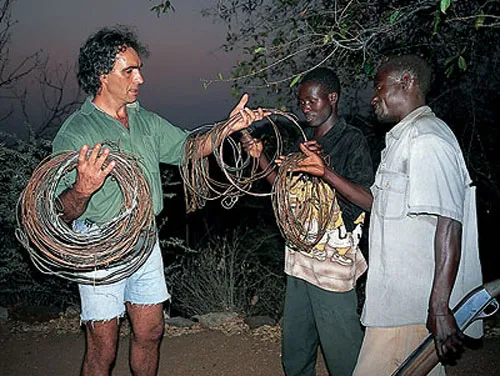

Jean-Roger Paolillo tries to keep the poachers away from the hippos. “I patrol our land every day, removing any snares I find and shooting the poachers’ hunting dogs if I see them. I hate doing that, but I have to protect the wild animals. The invaders have retaliated by cutting our phone lines four times and twice surrounding our house and threatening to burn it down.”

The Paolillos faced their most severe crisis in February 2005, when a group of Youth Brigades and two uniformed policemen appeared outside their door one morning. Shouting that Jean had killed someone, they marched him to the river. The dead man was a poacher, Jean says. “He had gone into a hippo tunnel in the reeds, and his companions said all they found of him were scraps of his clothing, blood smears and drag marks leading to the water.”

Karen speculates that the poacher must have encountered a hippo called Cheeky, who was in the reeds with a newborn: “We think Cheeky killed the poacher when he stumbled on her and the calf, and then a crocodile found the body and dragged it into the water for a meal,” she says.

The policemen arrested and handcuffed Jean and said they were taking him to the police station, an eight-hour trek through the forest. They released him, but the charge still stands while the police investigate. He says that a mob led by a veteran guerrilla commander came to his house after the arrest and told Jean that unless he left immediately he would disappear in the bush.

Karen bristles at the retelling. “I refuse to leave the hippos,” she says.

They call the place Hippo Haven, and that pretty much sums up the Paolillos’ approach. They aren’t academic scientists. They haven’t published any articles in learned journals, and they don’t claim to be in the forefront of hippo ethology. They’re zealots, really, in a good sense of the word: they’ve thrown themselves wholeheartedly into this unlikely mission to protect a handful of vulnerable animals. Even though they might be better trained in blackjack and geology than in mammalian biology, they’ve spent so many hours with these under-studied giants that they do possess unusual hippopotamus know-how.

Watching these hippos for so many years, Karen has observed some odd behaviors. She shows me a video of hippos grooming big crocodiles, licking the crocs’ skin near the base of their tails. “I think they’re getting mineral salt from the skin of the crocodiles,” Karen suggests. She has also seen hippos tugging the prey of crocodiles, such as goats, from the reptiles’ mouths, as if to rescue them.

Hippos appear to sweat blood. Paolillo has observed the phenomenon, saying they sometimes secrete a slimy pink substance all over their bodies, particularly when they are stressed. In 2004, researchers at KeioUniversity in Japan analyzed a pigment in the hippo secretion and concluded that it may block sunlight and act as an antibiotic, hinting that the ooze might help skin injuries heal.

Like many people who take charge of wild animals, Karen has her favorites. Bob, the pod’s dominant male when Karen arrived, learned to come when she called him. “He’s the only hippo who ever did this for me,” she says. So she was astonished one day when it seemed that Bob was charging her. She was certain she would be trampled—then realized that Bob was heading for a nine-foot crocodile that was behind her and poised to grab her. “Bob chased the crocodile away,” she says.

Two years ago in February a hunting-camp guard told her that Bob was dead in the river. “My first fear was that a poacher had shot him, but then I noticed a gaping hole under his jaw from a fight with another bull. He had been gored and bled to death,” Karen remembers. “I cried [because I was] so glad that he had died as a bull hippo, in a fight over females, and not by a bullet.”