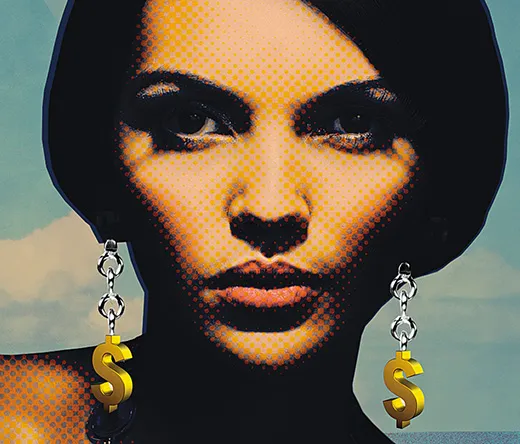

How Much is Being Attractive Worth?

For men and women, looking good can mean extra cash in your bank account

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Beauty-The-Price-of-Beauty-631.jpg)

Beautiful people are indeed happier, a new study says, but not always for the same reasons. For handsome men, the extra kicks are more likely to come from economic benefits, like increased wages, while women are more apt to find joy just looking in the mirror. “Women feel that beauty is inherently important,” says Daniel Hamermesh, a University of Texas at Austin labor economist and the study’s lead author. “They just feel bad if they’re ugly.”

Hamermesh is the acknowledged father of pulchronomics, or the economic study of beauty. It can be a perilous undertaking. He once enraged an audience of young Mormon women, many of whom aspired to stay home with future children, by explaining that homemakers tend to be homelier than their working-girl peers. (Since beautiful women tend to be paid more, they have more incentive to stay in the work force, he says.) “I see no reason to mince words,” says the 69-year-old, who rates himself a solid 3 on the 1-to-5 looks scale that he most often uses in his research.

The pursuit of good looks drives several mammoth industries—in 2010, Americans spent $845 million on face-lifts alone—but few economists focused on beauty’s financial power until the mid-1990s, when Hamermesh and his colleague, Jeff Biddle of Michigan State University, became the first scholars to track the effect of appearance on earnings potential for a large sample of adults. Like many other desirable commodities, “beauty is scarce,” Hamermesh says, “and that scarcity commands a price.”

A handsome man is poised to make 13 percent more during his career than a “looks-challenged” peer, according to calculations in Hamermesh’s recent book, Beauty Pays. (Interestingly, the net benefit is slightly less for comely women, who may make up the difference by trading on their looks to marry men with higher earning potential.) And some studies have shown that attractive people are more likely to be hired in a recession.

“Lookism” extends into professions seemingly detached from aesthetics. Homely quarterbacks earn 12 percent less than their easy-on-the-eyes rivals. “Hot” economics professors—designated by the number of chili peppers awarded on Ratemyprofes-sors.com—earn 6 percent more than members of their departments who fail to garner accolades along these lines.

Hamermesh argues that there’s not much we can do to improve our pulchritude. There are even studies suggesting that for every dollar spent on cosmetic products, only 4 cents returns as salary—making lipstick a truly abysmal investment.

But inborn beauty isn’t always lucrative. One 2006 study showed that the unbecoming may actually profit from their lack of looks. People tend to expect less from the unattractive, so when they surpass those low expectations they are rewarded. And the pulchritudinous are often initially held to a higher standard—then hit with a “beauty penalty” if they fail to deliver. “You might see this as wages being depressed over time,” says Rick K. Wilson, a Rice University political scientist who co-authored the study. “We have these really high expectations for attractive people. By golly, they don’t often live up to our expectations.”