How Technology Makes Us Better Social Beings

Sociologist Keith Hampton believes technology and social networking affect our lives in some very positive ways

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/social-media-Keith-Hampton-631.jpg)

About a decade ago, Robert Putnam, a political scientist at Harvard University, wrote a book called Bowling Alone. In it, he explained how Americans were more disconnected from each other than they were in the 1950s. They were less likely to be involved in civic organizations and entertained friends in their homes about half as often as they did just a few decades before.

So what is the harm in fewer neighborhood poker nights? Well, Putnam feared that fewer get-togethers, formal or informal, meant fewer opportunities for people to talk about community issues. More than urban sprawl or the fact that more women were working outside the home, he attributed Americans’ increasingly isolated lifestyle to television. Putnam’s concern, articulated by Richard Flacks in a Los Angeles Times book review, was with “the degree to which we have become passive consumers of virtual life rather than active bonders with others.”

Then, in 2006, sociologists from the University of Arizona and Duke University sent out another distress signal—a study titled “Social Isolation in America.” In comparing the 1985 and 2004 responses to the General Social Survey, used to assess attitudes in the United States, they found that the average American’s support system—or the people he or she discussed important matters with—had shrunk by one-third and consisted primarily of family. This time, the Internet and cellphones were allegedly to blame.

Keith Hampton, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, is starting to poke holes in this theory that technology has weakened our relationships. Partnered with the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, he turned his gaze, most recently, to users of social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn.

“There has been a great deal of speculation about the impact of social networking site use on people’s social lives, and much of it has centered on the possibility that these sites are hurting users’ relationships and pushing them away from participating in the world,” Hampton said in a recent press release. He surveyed 2,255 American adults this past fall and published his results in a study last month. “We’ve found the exact opposite—that people who use sites like Facebook actually have more close relationships and are more likely to be involved in civic and political activities.”

Hampton’s study paints one of the fullest portraits of today’s social networking site user. His data shows that 47 percent of adults, averaging 38 years old, use at least one site. Every day, 15 percent of Facebook users update their status and 22 percent comment on another’s post. In the 18- to 22-year-old demographic, 13 percent post status updates several times a day. At those frequencies, “user” seems fitting. Social networking starts to sound like an addiction, but Hampton’s results suggest perhaps it is a good addiction to have. After all, he found that people who use Facebook multiple times a day are 43 percent more likely than other Internet users to feel that most people can be trusted. They have about 9 percent more close relationships and are 43 percent more likely to have said they would vote.

The Wall Street Journal recently profiled the Wilsons, a New York City-based family of five that collectively maintains nine blogs and tweets incessantly. (Dad, Fred Wilson, is a venture capitalist whose firm, Union Square Ventures, invested in Tumblr, Foursquare and Etsy.) “They are a very connected family—connected in terms of technology,” says writer Katherine Rosman on WSJ.com. “But what makes it super interesting is that they are also a very close-knit family and very traditional in many ways. [They have] family dinner five nights a week.” The Wilsons have managed to seamlessly integrate social media into their everyday lives, and Rosman believes that while what they are doing may seem extreme now, it could be the norm soon. “With the nature of how we all consume media, being on the internet all the time doesn’t mean being stuck in your room. I think they are out and about doing their thing, but they’re online,” she says.

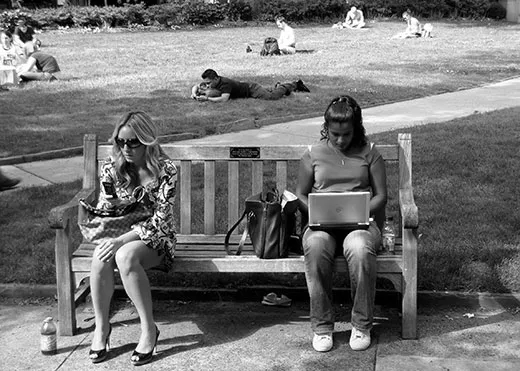

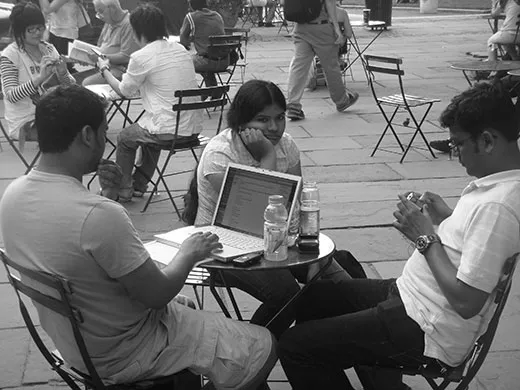

This has been of particular interest to Hampton, who has been studying how mobile technology is used in public spaces. To describe how pervasive Internet use is, he says, 38 percent of people use it while at a public library, 18 percent while at a café or coffee shop and even 5 percent while at church, according to a 2008 survey. He modeled two recent projects off of the work of William Whyte, an urbanist who studied human behavior in New York City’s public parks and plazas in the 1960s and 1970s. Hampton borrowed the observation and interview techniques that Whyte used in his 1980 study “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” and applied them to his own updated version, “The Social Life of Wireless Urban Spaces.” He and his students spent a total of 350 hours watching how people behaved in seven public spaces with wireless Internet in New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Toronto in the summer of 2007.

Though laptop users tended to be alone and less apt to interact with strangers in public spaces, Hampton says, “It’s interesting to recognize that the types of interactions that people are doing in these spaces are not isolating. They are not alone in the true sense because they are interacting with very diverse people through social networking websites, e-mail, video conferencing, Skype, instant messaging and a multitude of other ways. We found that the types of things that they are doing online often look a lot like political engagement, sharing information and having discussions about important matters. Those types of discussions are the types of things we’d like to think people are having in public spaces anyway. For the individual, there is probably something being gained and for the collective space there is probably something being gained in that it is attracting new people.” About 25 percent of those he observed using the Internet in the public spaces said that they had not visited the space before they could access the Internet there. In one of the first longitudinal studies of its kind, Hampton is also studying changes in the way people interact in public spaces by comparing film he has gathered from public spaces in New York in the past few years with Super 8 time-lapse films that were made by William Whyte over the decades.

“There are a lot of chances now to do these sort of 2.0 versions of studies that have been ongoing studies from the ’60s and ’70s, when we first became interested in the successes and failures of the cities that we have made for ourselves,” says Susan Piedmont-Palladino, a curator at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. Hampton spoke earlier this month at the museum’s “Intelligent Cities” forum, which focused on how data, including his, can be used to help cities adapt to urbanization. More than half of the world’s population is living in cities now and that figure is expected to rise to 70 percent by 2050.

“Our design world has different rates of change. Cities change really, really slowly. Buildings change a little faster, but most of them should outlive a human. Interiors, furniture, fashion—the closer you get to the body, the faster things are changing. And technology right now is changing fastest of all,” says Piedmont-Palladino. “We don’t want the city to change at the rate that our technology changes, but a city that can receive those things is going to be a healthy city into the future.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)