How the Pogo Stick Leapt From Classic Toy to Extreme Sport

Three lone inventors took the gadget that had changed little since it was invented more than 80 years ago and transformed it into a gnarly, big air machine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Extreme-Pogo-jumping-631.jpg)

The pogo stick may never upend the wheel as a means of locomotion. But as inventions go, they share something: Once built, there wasn’t a whole lot anyone could seem to do to improve the basic design. In the more than eight decades since a Russian immigrant named George B. Hansburg introduced the pogo stick to America, the device had scarcely changed: a homely stilt with foot pegs and a steel coil spring that bopped riders a few inches off the ground. And bopped. And bopped. And bopped. Some kids fell off so many times they gave up, tossing the pogo next to the dinged hula hoops and unicycle deep in the garage. Others just outgrew it, gaining enough weight as teenagers to snap the stick or snuff the spring.

But not long ago, three inventors—toiling at home, unaware of one another’s existence—set out to reimagine the pogo. What was so sacred about that ungainly steel coil? they wondered. Why couldn’t you make a pogo stick brawny enough for a 250-pound adult? And why not vault riders a few feet, instead of measly inches? If athletes were pulling “big air” on skateboards, snowboards and BMX bikes, why couldn’t the pogo stick be just as, well, gnarly?

When I reached one of the inventors, Bruce Middleton—who studied physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and describes himself as an “outcast scientist”—he told me that the problem had been a “conceptual basin.”

“Normal people, someone tells them a pogo stick is a thing with steel springs, they go, ‘That’s right,’” Middleton said. “If that’s your basin, you’ll never come up with a very good pogo. An inventor is someone who recognizes the existence of a conceptual basin and sees that there’s a world outside the basin.”

That world turned out to be a perilous place. In their quest for Pogo 2.0, the inventors endured bouts of unconsciousness, defective Chinese imports, trips to the bank for second mortgages and an exploding prototype that sent one test pilot to the hospital for reconstructive surgery.

“It’s a really challenging thing if you think about the forces involved,” Middleton told me. He is talking, here, about forces that could fling a grown-up six feet in the air. “It’s a matter of life and death that it doesn’t break. So you’re taking on something that has to be built in a very serious way, and it has to come in on a kind of toy budget. And it has to be rugged enough that when people bail, and they’re four to five feet in air...it has to be rugged enough to take that. When you actually start thinking about what your design parameters are, it turns out it’s a horrific design challenge.”

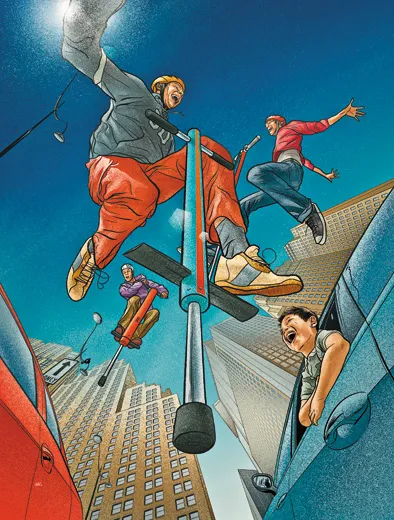

In time, Middleton, along with two other inventors—a robotics engineer at Carnegie Mellon University and a retired California firefighter—would see their ideas take wing. The Guinness Book of World Records would establish a new category—highest jump on a pogo stick—which a 17-year-old Canadian, Dan Mahoney, would set in 2010 by leaping, pogo and all, over a bar set at 9 feet 6 inches. Pogopalooza, an annual competition that started in 2004 with six guys in a church parking lot in Nebraska, graduated last year to a sports arena at the Orange County (California) fair. It drew thousands of fans and 50 of the world’s best practitioners of “extreme pogo.”

After one inventor’s son pogoed over a New York City taxicab on the “Late Show with David Letterman,” the host, looking uncharacteristically sincere, turned to the camera and said, “That’s the most exciting thing I’ve seen in all my life—honest to God.”

But I hop ahead. Before Guinness and Letterman and the television lights, there were just three ordinary men, on lonely journeys, convinced that somewhere out there was a better pogo.

Ben Brown’s house is on a winding street in the Pittsburgh suburbs. When I showed up, the 67-year-old robotics engineer answered the door in an ornately lettered sweatshirt that said, “I make stuff.”

A slight man with a stubbly gray beard and elfin features, Brown led me down a set of creaky stairs to his basement workshop. A smorgasbord of screws, wires and electronic capacitors filled rows of washed-out peanut butter jars that Brown had somehow affixed to the ceiling. In the world of robotics, one of his colleagues told me, Brown has a reputation as a “mechanical designer extraordinaire.”

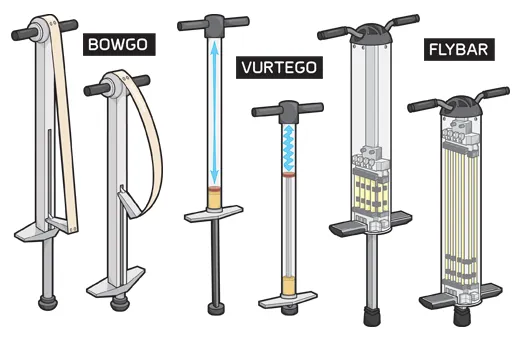

“This is the graveyard,” Brown said, nodding at piles of wooden dowels, fiberglass strips and slotted aluminum shafts—detritus from the decade he’s spent refining his pogo stick, the BowGo. Razor, the company that rode the toy scooter to riches in the early 2000s, licensed Brown’s technology in 2010 and sells a children’s version of his stick, which they call the BoGo.

Brown developed the BowGo to prove a simple idea: that with the right design and materials, a lightweight spring could conserve an extraordinarily high share of the energy put into it, with minimal losses to friction.

“A pogo looks to us like a toy,” said Matt Mason, the director of Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute, where Brown has worked for three decades. “To Ben, it’s an idea taken to its most radical extreme.”

Brown, a onetime mechanical engineer for Pittsburgh’s steel mills, joined Carnegie Mellon in the early 1980s and worked on Defense Department-funded research into “legged locomotion”—robots that walk, run and hop. The military was interested in vehicles that balanced on legs and could roam mountainsides, swamps and other terrain too rugged for trucks or tanks.

Brown and his colleagues built a stable of hopping one-legged robots that could leap over objects and move nimbly at nearly five miles per hour without losing their balance. But the hoppers—picture a 38-pound bird cage on a swiveling stilt—were energy hogs. Powered by hydraulics and compressed air, they had to be tethered to pumps, electrical outlets and computers. Brown was left wondering: Could you build a leg light and efficient enough to bounce without external power?

“Kangaroos were always inspiring,” Brown told me, “because the kangaroo uses an Achilles tendon that stores a huge amount of energy and allows it to hop efficiently.”

In the late 1990s he and a graduate student, Garth Zeglin, bent a six-inch length of piano wire and joined the ends with a piece of string that held the wire taut, like a bow. They called it a “bow leg,” and tested it on an inclined air-hockey table. When dropped, the leg flexed and recoiled, bouncing back to between 80 and 90 percent of its original height, a feat of energy conservation.

Brown wanted to put his idea to a bigger test. One route would be to build a battery-powered, human-size hopping robot with an onboard computer, stabilizing gyroscope and giant bow leg. He opted instead for a pogo stick.

“It was really the easiest way to build a robot without all the robot technology,” Brown said. The only power source, thrust actuator, leg position controller and altitude sensor you needed was a flesh-and-blood rider.

In 2000, Brown and another Carnegie Mellon engineer, Illah Nourbakhsh, built their first BowGo prototype. Instead of piano wire, they bolted a strip of structural-grade fiberglass to the outside of the pogo’s aluminum frame. They fastened the top of the fiberglass strip near the handlebars and the bottom to the plunger. When a rider lands and the plunger shuttles through the frame, the strip flexes and then abruptly straightens, reversing the plunger and launching the rider skyward with as much as 1,200 pounds of force. Ounce for ounce, they discovered, this fiberglass “leaf spring” stored as much as five times the elastic energy as a conventional steel coil.

After a couple of years of field testing in his backyard and on campus greens, Brown pogoed over a bar set at 38 inches. “A couple of times, the foot slipped out and I was unconscious for a bit,” Brown recalled. “I remember some guy standing over me and saying, ‘Do you know your name?’”

It became clear that Brown, a grandfather of four, needed a younger test pilot. He shipped a prototype to Curt Markwardt, a Southern California video game tester who learned his first tricks on a $5 pogo stick that a friend had bought as a joke at a toy store’s going-out-of-business sale.

Within months Markwardt had somersaulted on the BowGo over his car and cleared a bar set at 8 feet 7 inches, a record. When he’d first told friends about his passion for pogo, “people would kind of chuckle,” Markwardt told me. “They think of little kids bopping up and down and not doing anything.” But when “they see you jump six feet in the air and you do a flip, holy cow...it turns into instant awesome.”

Brown is eager for Razor to release an adult version of his stick, but so far, only the children’s model is for sale. The bow leg, meanwhile, is still kicking. In 2008, Brown and a team of colleagues won a grant from the National Science Foundation to develop the technology into a lightweight “parkour bot” that climbs by leaping between parallel walls.

When Bruce Spencer retired after 28 years as a firefighter in Huntington Beach, California, he imagined a simpler life. A husky man with a broad brow and ruggedly handsome features, he dreamed of flying his two-passenger Cessna to Idaho and Colorado and scouting the wilderness for a patch of earth to build a cabin and live out his years with his wife, Patti, in quiet.

A few months after leaving the department, though, Spencer hosted a family party. His nephew Josh Spencer had built a prototype adult-size pogo stick, stuffing a 33-inch steel spring into an aluminum tube. But the weight of all that metal made the stick unwieldy. Josh was venting about it at the party, and Bruce Spencer’s son Brian went to his dad for advice.

“Brian comes in and says, ‘Hey Dad, if you ever made a big pogo stick for adults, how would you do it?’” Bruce Spencer recalled.

Before joining the fire department, Spencer had earned a degree in aerospace engineering and worked at Northrop on the design team for a lightweight fighter jet that would become the F-18. His son’s question lit up a dormant part of his brain.

Spencer penciled a diagram in the margins of a newspaper. “Make an air spring,” he told his son, “because it would be very light.” With that, he considered himself rid of the matter. “Just fun and games,” he told me, with the tone of a man recalling a spell of youthful naiveté.

A few months later, Brian, a charismatic marketing executive, announced that he’d found an investor. He handed his father a check for $10,000.

Roused by the engineering challenge, Bruce Spencer dove into the project with such zeal that his wife often found him awake at night trying to unravel some pogo-related physics problem.

His first prototype was a Rube Goldberg mishmash of PVC irrigation pipe from Home Depot, truck tire valves, and pistons he machined in his garage. He found a polyurethane shock absorber at an off-road supply store and bolted it to the foot of the pogo to cushion landings. He pressurized the irrigation pipe to about 50 pounds per square inch with an air compressor.

When I asked Spencer for an everyday example of an air spring, he stood up from his desk chair and plopped back down. The seat dipped an inch or so under his weight, then rebounded, thanks to pressurized air in its support column. “It’s core technology,” he told me. “And no one had really made it work in a pogo stick.”

Spencer’s first prototypes worked, but the plunger recoiled with such vehemence that he felt as if he were riding a jackhammer. To sell his sticks commercially, he’d need a smoother ride.

He’d studied Boyle’s law in college and recalled that volume and pressure were inversely proportional: Compress air to half its original volume and the pressure doubles; compress volume by another half and pressure doubles again.

If you tried to squeeze air into anything smaller than a quarter of its original volume, Spencer discovered, you got the jackhammer effect. The only way to keep the “compression ratio” low while still producing enough thrust to lift an adult rider was to use the entire length of the pogo cylinder as an air spring. Once he demonstrated this insight, examiners at the U.S. Patent Office certified the novelty of his invention.

He spent the next year experimenting with tube materials, pressure seals and lubricants. To make sure the pogo cylinder could withstand enormous pressures, he drove to a local park in the early mornings, dropped a tube inside a 55-gallon steel drum, and slid the whole rig into a batting cage. He put in earplugs, took cover behind a concrete water fountain and cranked up the pressure in the tube with a nitrogen tank until the tube exploded.

“Then I’d pick up the pieces, throw everything in the trunk and drive away before the cops came,” he told me, half jokingly. He found that the cylinder could withstand pressures of nearly 800 pounds per square inch, more than three times what an adult rider was apt to produce.

The Spencers took 16 prototypes of their stick—the Vurtego, they called it—to the Ice Village at the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City. They were a hit with tourists, visiting athletes and TV cameras. “When I came home, I thought I’d have people champing at the bit to invest in the company,” Bruce said. “It didn’t happen.”

The economy was still limping after 9/11, and the proposed $300 price tag and dicey liability issues made investors wary. For two years, his pogo sticks gathered dust on a rack in the garage.

Then, in September 2004, SBI Enterprises, the makers of the original pogo stick, released the Flybar, a high-powered pogo designed by Bruce Middleton. The Spencers despaired they’d missed the boat, but eventually glimpsed opportunity. The publicity surrounding the Flybar was helping establish a market for extreme pogo sticks.

Bruce Spencer took out a $180,000 home equity loan, a friend chipped in another $180,000, and Spencer undertook a series of refinements to prepare the Vurtego for its commercial debut.

In December 2005, a month before the launch, they suffered an almost catastrophic setback. Brian Spencer, a lithe former college linebacker who had become Vurtego’s chief test pilot, was pogoing in his driveway on a prototype made of wound fiberglass filament, a strong, ultralight material used to reinforce the exterior of high-pressure scuba tanks. He had bounced to heights of about five feet when the pressurized tube snapped. Its top half rocketed into his chin, pushing his four front teeth into his nose, shattering his jaw and almost completely severing his bottom lip.

“Blood everywhere,” Brian Spencer told me when I visited the family in California. “It was the first time I heard my dad swear.”

Brian underwent plastic surgery to reattach his lip, repair his nose and implant five false teeth. He still lacks feeling in his lower lip.

“At that point, I said, ‘That’s it, I’m pulling the plug,’” Bruce Spencer recalled.

But Brian was undeterred. “I didn’t donate my face so we could fail,” he told his father. (An analysis found the tube defective; Brian won a settlement from its maker.)

Unwilling to risk another failure, Bruce Spencer turned to heavier but tougher materials, first a space-age thermoplastic and, finally, aerospace aluminum. Riders could pressurize the tube with an ordinary bike pump. The Spencers sold their first Vurtego in January 2006. Brian soon leapt over that taxicab on Letterman’s show. In August 2010, at Pogopalooza 7, in Salt Lake City, Mahoney, the Canadian, set a new pogo high-jump record—on a Vurtego. The Spencers told me they sell around 800 a year, all through their website.

I met with Bruce and Brian Spencer in a narrow, sky-lit work space in a nondescript commerce park in Mission Viejo, where they personally assemble their pogo sticks. Saddleback Mountain rose in the haze beyond the parking lot.

It was a Wednesday afternoon, a week and a half before Christmas, and father and son were scurrying to stay atop a rush of holiday business, including a first-ever order from Egypt, the 42nd country in which Vurtego has found customers.

I had a hard time tracking down Bruce Middleton, who would eventually tell me his theory of “conceptual basins.” Old e-mails and phone numbers didn’t work, and his name was common enough to make identifying the right man tricky. I eventually found him on Facebook, which his daughter had nudged him to join.

His life had seen some ups and downs since his Flybar pogo stick came to market. When we spoke by phone, he told me that he had split with SBI Enterprises. He was now living in a single-room-occupancy hotel on skid row in Vancouver, British Columbia. (Middleton said the company owed him money; SBI’s president told me the parting was amicable.)

“I thought my 15 minutes of pogo fame were all finished,” Middleton replied, dryly, to my first Facebook message.

I said I was interested less in his fame, such as it was, than in the workings of an inventor’s mind. How does a grown man decide that a quiver of giant rubber bands is the key to pogo’s progress?

Middleton, 55, told me that the Flybar was his answer to a question that came to him when he was 16. His girlfriend had lived 15 miles away, on the other side of Vancouver’s Lions Gate Bridge. During bike rides to her house, after reaching high speeds, he hated having to brake at lights and squander all that kinetic energy.

Might there be some way to store the energy lost to braking? Could you convert it to potential energy and then release it to propel you back to your original speed? (A form of such “regenerative braking” is now standard in hybrid vehicles like the Toyota Prius and Honda Insight.)

For decades, the question remained one of the many intellectual riddles caroming around his brain. Middleton entered MIT at age 16, with dreams of becoming a theoretical physicist. He soon suffered what he termed a “moral crisis” over the detachment of science from real-world problems like global poverty, and dropped out .

He traveled to Venezuela to tend to disabled children at one of Mother Teresa’s outposts. Back in Canada, he worked a series of menial jobs—parks laborer, millworker—and eventually became a stay-at-home dad. In the late 1990s, he began bicycling with his two young daughters to their school and found himself newly curious about regenerative braking.

He considered affixing some kind of steel spring to his bike. But he concluded that a strong enough steel coil would easily weigh as much as an adult rider. Rubber was lighter than steel and, pound for pound, could store as much as 20 times the energy. Still, he’d need more rubber than could be elegantly integrated into a bicycle frame.

Then it came to him: a pogo stick. “I realized that, Hey, yeah, a pound of rubber could store enough energy to bounce a person five to six feet in the air.”

He built a frame with wooden planks from an old Ikea couch. Then he bought a roll of industrial-grade surgical tubing from a medical supply store. He fashioned a spring by looping the tubes from steel anchors at the frame’s bottom to hooks he’d drilled into the piston. When a rider jumped down, the piston would stretch the rubber tubes to four times their resting length.

After a few rounds of improvements, he asked his daughter’s gymnastics coach to give his pogo a bounce. “Within minutes,” Middleton told me, “he was jumping five feet in the air.”

In 2000, he sent a demo video to Irwin Arginsky, the president of SBI Enterprises, manufacturers of the original pogo stick, in upstate New York. SBI officials had belittled earlier efforts to soup up the pogo. “There’s not a heck of a lot you can change on the pogo stick,” Bruce Turk, then SBI’s general manager, told the Times Herald-Record of Middletown, New York, in 1990. “Once you try, you’re in trouble.”

But a decade later, when they sat down and watched Middleton’s video, “our jaws dropped,” Arginsky told me.

SBI Enterprises spent four years and nearly $3 million turning the Flybar into a marketable sporting device. Compared with the Vurtego or BowGo, the Flybar is a complex design involving 12 solid rubber tubes—or “thrusters”—that latch onto mounts surrounding the piston. Individual tubes, which generate 100 pounds of force each, can be slipped off to adjust for rider weight or fear of heights.

Arginsky signed up Andy Macdonald, an eight-time World Cup Skateboarding champion, to field-test and promote Middleton’s stick. Macdonald loved its trampoline-like feel, but broke dozens of prototypes as Flybar’s “crash-test dummy” before he and Middleton arrived at a safe design. The collaboration between skateboarding pro and introverted scientist appears to have had its share of droll moments. “Bruce was the numbers guy—very much the physicist,” Macdonald told me. “He’d be talking in these scientific terms about storage and energy and thrust and per-pound blah, blah, and I’d be like, ‘Yeah, that’s rad, dude.’”

Read about the feud between pogo scientists over "Theory" vs. "The Real World" »

The pogo stick had its heyday in the Roaring Twenties, after Hansburg, its inventor, helped teach Broadway’s Ziegfeld Follies to bounce. The Ziegfeld girls did dance routines on the sticks and staged what was perhaps the world’s first (and last) pogo-mounted marriage.

Along with the red wagon and hula hoop, the stick became iconic of a kind of idyllic American childhood. Still, demand has been mostly earthbound. “You’re not talking about a hot toy,” Arginsky, who bought the company from Hansburg in 1967, told me. “You’re talking about a market that maybe—maybe—we topped out one year at 475,000 units.” And that’s conventional pogos. SBI recently changed its name to Flybar Inc., but the extreme stick represents a “very small fraction” of overall sales.

When I made an electronic search of files at the U.S. Patent Office, I found ideas for a gas-powered internal combustion pogo (1950) and a pogo with helicopter blades “for producing a gliding descent between jumps” (1969). In 1967, a Stanford University engineer unveiled designs for a “lunar leaper,” a 1,200-pound vehicle with a pneumatic shaft that could bounce astronauts, in 50-foot arcs, across the low-gravity surface of the moon. In 1990, a San Jose man patented a pogo that crushes beer cans.

None of these adaptations took; some never got built, others never found a market. But why not? And why have others taken off now? The more I talked to Brown, Spencer and Middleton, the more convinced I became of the importance of culture—and timing. The late 1990s saw the rise of “extreme sports” and a generation of teenage mavericks doing stomach-churning tricks on skateboards, snowboards and BMX bikes. The advent of ESPN’s annual X Games gave currency to phrases like “big air,” “vert” and “gnarly.” Soon the label “extreme” was being attached to every manner of boundary-testing contest, from eating to couponing.

But neither Brown nor Middleton was aware of the extreme sports scene when he began; Spencer, though familiar with skis and surfboards, never saw his pogo as any sort of rival. The trio’s motivation—simply to shake up a tired design—was probably not unlike those of earlier inventors whose ideas never got off the ground.

What none of the men knew then was that teenagers weaned on the X Games were rummaging through their garages for any old gizmo to take higher, farther or faster. The pogo appealed to kids who couldn’t—or didn’t want to—compete with the skateboarding hordes or who saw in its goofiness a kind of geeky cool. For several years before the supercharged pogos came to market, teenagers were refining low-altitude tricks like grinds and stalls on conventional sticks and swapping ideas and videos on websites like the Pogo Spot and Xpogo.

This time, when inventors came along with a new and better design, there was a market waiting—and a culture that could make sense of it as the latest extreme pastime.

I caught up not long ago with a few of the country’s best extreme pogoers. A Pittsburgh TV station had hired three members of a troupe known as the Pogo Dudes to perform in a parade.

Fred Grzybowski, a compactly built athlete who is the group’s éminence gris at 22, had driven to town with Tone Staubs and Zac Tucker, all from Ohio. Grzybowski ekes out a living with public performances, corporate functions and commercials. Staubs, 19, has kept his day job at a gas station. Tucker, 16, is a high-school junior.

The night before the parade, I watched a rehearsal in a faintly lit parking lot near Carnegie Mellon. The first thing I noticed was a set of cylinders that looked more like shoulder-mounted rocket launchers than any pogo I remembered from childhood.

Grzybowski, in hoodie and jeans, docked his iPhone into a portable speaker and cranked up the song “Houdini,” by Los Angeles indie rockers Foster the People. The Pogo Dudes were soon leaping through a routine of gravity-snubbing stunts with names like “air walk,” “switch cheese” and “under-the-leg bar spin.” (Fred rides a Flybar; Tone and Zac, Vurtegos.)

At a VIP brunch at a local Marriott after the parade, Grzybowski told me that he’d gotten his first pogo for Christmas when he was 8. It was a plastic stick with an anemic steel spring. But he persevered, learning to ride with no hands or while eating a Popsicle.

Transposing skateboard tricks to a pogo made him feel as if he were “creating something new,” he told me. But it wasn’t until he saw previews of the Flybar and Vurtego on the Xpogo website that he grasped how far his eccentric hobby might take him.

“I don’t think we would be where we are without the technology,” Grzybowski, regarded for a time as the best pogoer in the world, told me. “The technology pushed us forward and made us see new tricks were possible.” In an action sports culture that prized “big air,” he said, “the bigger sticks added legitimacy.”

They were also just a lot of fun. “It’s a weightless feeling,” Staubs told me, as he massaged a sore knee after the parade. “It puts this feeling inside your head that you can go high, you can do anything, you’re invincible.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sabar_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sabar_copy.jpg)