How Witches’ Brews Helped Bring Modern Drugs to Market

Got nausea, headaches or heart trouble? You can thank medieval witches’ potions for helping to cure what ails you

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/08/05081855-6b79-4053-9861-5cd91820145d/witchespumpkinedit.jpg)

“Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.”

There’s no more iconic image of witchcraft that that conjured by Shakespeare in the opening act of Macbeth. Every Halloween we revisit the fictional trope of witches stirring cauldrons full of colorful ingredients: venomous toads, animal tongues, a dead man’s toes. While the Bard tapped into a real fear of witchcraft and the occult in Elizabethan society, it’s unlikely that most people prosecuted as witches during Shakespeare’s time and earlier in the Middle Ages brewed potions for truly nefarious purposes. Instead, most potions probably contained intoxicants or folk remedies.

Perhaps the most striking example of witchcraft’s influence on medicine comes from psychotropic plant compounds associated with “flying ointments,” salves reportedly created as magical aids during the height of the European witch-hunting craze in the 1500s and 1600s. In 1545, Spanish physician Anres Laguna provided an account of one such ointment found at the residence of an elderly couple suspected of witchcraft:

“… a jar half-filled with a certain green unguent … with which they were anointing themselves … was composed of herbs … which are hemlock, nightshade, henbane, and mandrake.”

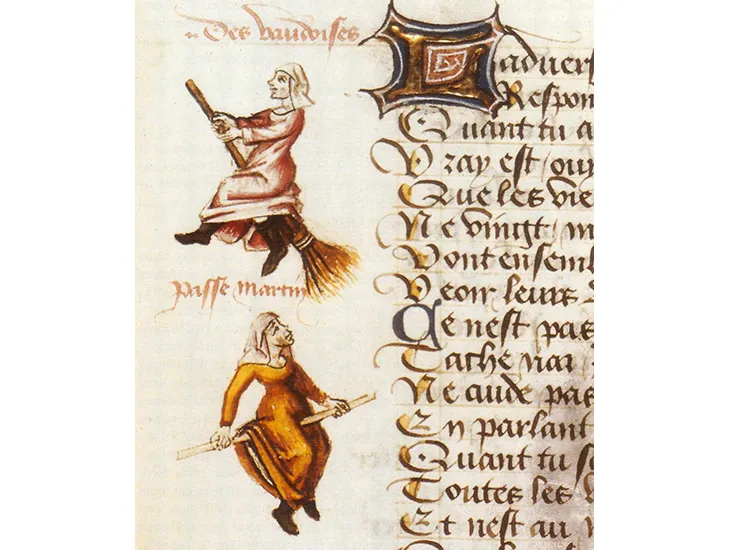

Some of these plants prove poisonous at high doses, but some also contain a tropane alkaloid called hyoscine. Native Americans used a hyoscine-rich plant called thorn apple (Datura stramonium) as a local anesthetic, but also in religious rituals, because at higher doses hyoscine can cause delirium and hallucinations. In medieval Europe, hyoscine’s association with magic may explain the link between witches and broomsticks.

Supposedly witches applied the salve to their skin—either under the arms or (for the daring) on the genitalia. Absorbing the chemicals through sweat ducts avoids the stomach and risk of poisoning. Hallucination and the altered mental state induced by hyoscine may have given medieval witches the illusion of flight. It’s unclear how widespread these flying ointments were, though, and some question the veracity of such claims, since prosecutors may have coerced the confessions. But a 1324 inquisitor’s account of a suspected witch, Lady Alice Kyteler, does paint an interesting image of the ointment in action:

“In rifleing the closet of the ladie, they found a pipe of oynment, wherewith she greased a staffe, upon which she ambled and galloped through thick and thin.”

Today hyoscine—also called scopolamine in the U.S.—is a common treatment for motion sickness, as low doses can relieve nausea and stomach cramps.

The ointment herbs henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) and mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) also contain other tropane alkaloids. From nightshade, 19th-century chemists isolated atropine—a muscle relaxant that was later used to calm patients during surgery before the administration of anesthesia. Atropine also remains the go-to antidote for nerve gas poisoning. Tropane alkaloids continued to prove useful as chemical backbones in 20th-century drug design, most notably producing the anti-psychotic drug haloperidol.

Other witches’ brews were probably intended to cure ailments from the start. Many of the women and men tried as witches in Europe during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance practiced midwifery or medicine. Doctors were scarce, and for members of Europe’s lower classes, local healers were often the only option. When medicine started to be regulated around 1200, women were barred from formal medical training at universities, and those that continued as physicians or midwives were sometimes labeled witches. A few were even tried for illegally practicing medicine.

While some of the potions and ointments intended as cures might have been pretty ineffective, a few ingredients lining a witch’s medicine cabinet probably exist in yours in some form. Willow bark would have been used to treat inflammation, because we now know it contains salicin, a compound that eventually gave rise to salicylic acid and later aspirin. Garlic was used to treat a variety of maladies from snakebites to ulcers, and today some garlic compounds have been marketed as blood clotting inhibitors.

Foxglove plants were also in the mix. Seventeenth century herbalist Nicolas Culpepper recommended it for epilepsy. But it’s a Scottish doctor named William Withering who is credited with pioneering the use of the plants’ extracts for heart problems. In 1775, a patient with “dropsy”—a term for swelling probably caused by heart disease—came to Withering’s Birmingham practice. No treatment seemed to work, so the patient sought a second opinion from a local Gypsy woman. She prescribed a potion containing an estimated 20 different plant ingredients, and he was cured.

Keen to learn its properties, Withering tracked down the healer and figured out that the active ingredient in her potion was purple foxglove (Digitalis purpurea). He then performed a clinical trial of sorts, testing different doses and formulations on 163 patients. Withering ultimately determined that drying and grinding up the leaves produced the best results in small doses. Digitalis plants gave us the modern heart failure drugs digoxin and digitoxin.

Plenty of traditional remedies have produced the staple drugs of today. Traditional Chinese medicine gave the world ephedrine for asthma. The Quechua people of Peru gave western medicine quinine for malaria. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the strange brews of weird sisters in the Middle Ages were not total hocus pocus.

Murder, Magic, and Medicine

The Penguin Book of Witches

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)