I Am Officially in Love With Cockroaches

And after you read this, you will be too

:focal(305x72:306x73)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/06/50064fbe-1ab9-4d4b-b1f0-49d858fb5aac/glowing-roaches.jpg)

In the late 1970s, entomologist Coby Schal was in the rainforests of Costa Rica, watching a wasp. Every few minutes, the wasp would soar up into the canopy and snatch a helpless insect, then buzz back down and bury its prey in a nest below ground. After watching this sequence unfold numerous times, Schal decided to dig up the lair to see what the wasp was up to. What he discovered was a miniature house of horrors.

“Every single cell within the nest was filled with cockroaches,” said Schal, a professor of entomology at North Carolina State University.

Each roach had been stung, paralyzed, and jailed in subterranean burrows filled with other roaches, like a particularly disgusting box of See’s chocolates. Those chambers also contained a single wasp egg, which would eventually hatch and devour the cockroaches in its larder before emerging from the ground to seek its own prey.

Being accustomed to the monstrosities of nature, Schal wasn’t too phased by the whole zombifying, eating-alive routine. What interested him far more about the subterranean death dungeon was the fact that he’d never seen any of these roach species before.

So he bagged the bugs up—over 20 different kinds in all—and sent them off to two of the late, great cockroach experts, Louis Roth and Frank Fisk. If anyone in the world knew what these roaches were, it’d be these guys.

But Roth and Fisk were just as clueless as Schal. Whatever these species were, they did not belong to the approximately 5,000 or so species of cockroaches known to science. And, though the story of the wasp finally found its way into publication in 2010, those species remain undescribed to this day, says Schal.

We’re talking about more than 20 kinds of cockroaches discovered one day in a wasp’s lair in Costa Rica. Animals never before seen by scientists and, perhaps, never seen since. Such is the almost inconceivable state of cockroach biodiversity.

I tell you this because I’ve been reading this book, Cockroaches: Ecology, Behavior and Natural History, and I don’t think there’s a more misunderstood group of animals out there. We think of cockroaches as dirty, disease-spreading scavengers that haunt our kitchens and scurry around our sewers, but this reputation is based almost entirely off of the dozen or so species that make a living off our scraps. All told, these human-loving cockroaches account for less than half of one percent of the cockroach species on Earth. We're talking 0.5 percent.*

But guys, I’m here to tell you that the rest of the roaches—the ones you’ve never seen, the ones you’ve never even heard of—represent some of the most bewildering diversity on planet Earth.

The giant burrowing cockroaches of Australia can grow more than three inches long and, when they’re above ground, are often mistaken for small tortoises. On the other end of the spectrum, the itty-bittiest cockroaches are less than one-third the size of the tortoise roaches' feces.

In fact, cockroaches such as Attaphila fungicola are so small, they hide out in the fungal gardens cultivated by leaf-cutter ants. When this speck of a species wants to expand its territory, it simply hitches a ride on any outgoing winged ants, such as the queens-in-waiting. It’s an intimate relationship; the roach will be present during the queen’s mating flight, and also when she goes house-hunting for a site upon which to build the new colony. Everywhere the queen goes, the roach will follow, like an antennae-wielding guardian angel. Or a living fanny pack.

Size is only the tip of the roachberg. Cockroaches also come in a seemingly endless array of shapes and colors. There are cockroaches with little devil horns used for flipping rival males onto their backs and guarding the entrance to a burrow. There are high-stepping cockroaches (Cardacopsis shelfordi) that look for all the world like ants, right down to the way they run.

The genus Prosoplecta has evolved to have the body shape and red and black colorations of ladybugs to trick birds into thinking they’re bad news. Then there are cockroaches who don’t need to feign danger, because they have chemical weapons of their own. Each is a brilliant metallic shade of orange, red, or yellow, an aposematic warning flag that proclaims: “I taste like absolute death.”

There are cockroaches that look so much like lightning bugs, early experts kept them in dark rooms expecting to see their butts light up. Alas, they learned that these roaches are only pretenders at bioluminescence.

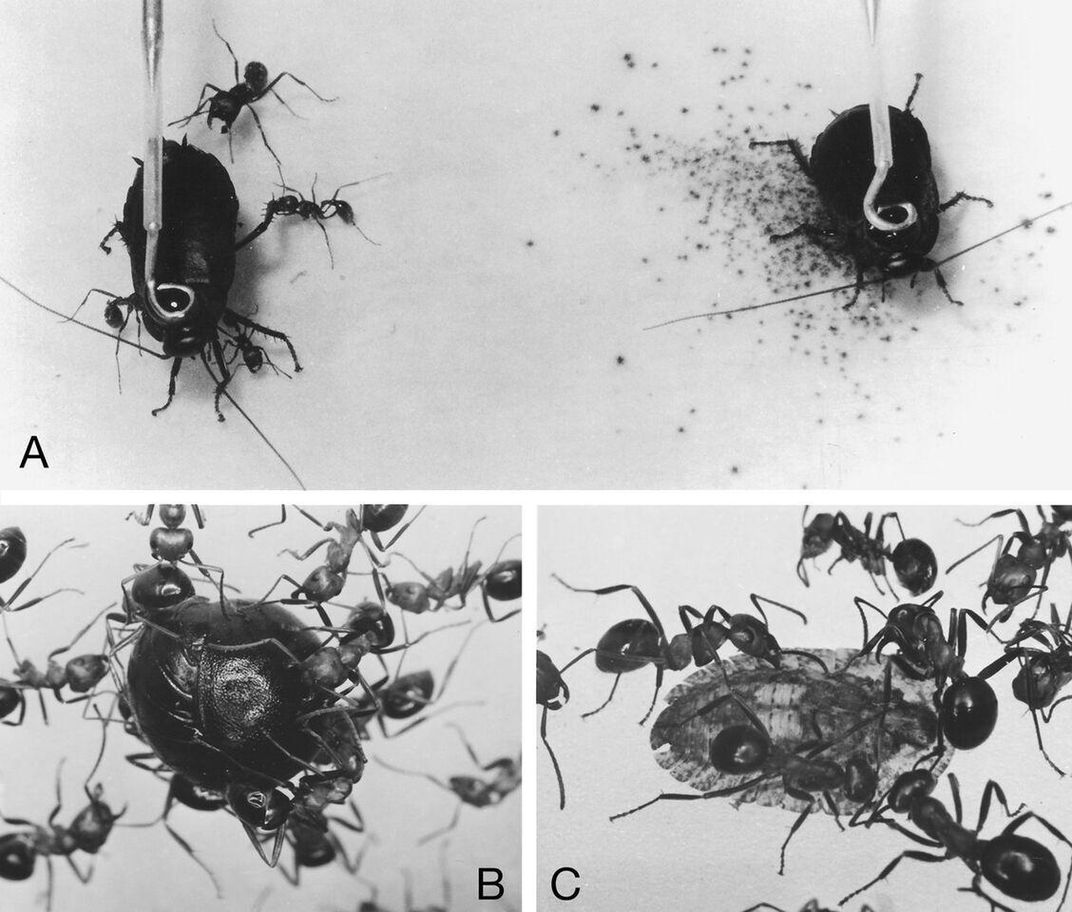

Does that disappoint you? I don’t want to disappoint you. So let’s talk about a cockroach that does have the goods. The glowspot cockroach, Lucihormetica fenestrata, is a nocturnal species that lives in the bromeliads of the Brazilian rainforest. The males have two bumps on their faces that burn like lanterns in the night, making them look like little Jawas from Star Wars. These glowing “headlights” are thought to play some role in wooing the lady cockroaches.

There are species that spend their lives wedged deep under bark or in the cracks of boulders and are so flat as to resemble a pancake. When enemy ants come a-marching, these roaches flatten even further and cling to whatever they’re standing on so tightly that there’s literally nothing for the ants to grab onto. These roaches are their own panic room.

Some cockroaches like the genus Colapteroblatta have pill-shaped bodies, the better for boring into logs. Others, like North America’s very own Cryptocercus, are built for tunneling into rotting logs and come equipped with shovel-shaped heads and articulated leg spikes for leverage.*

Desert dwelling cockroaches like the Iranian Leiopteroblatta monodi look a bit like Cousin Itt. You’d think species that have to cope with extreme heat would want less hair, but this fuzz actually creates a boundary layer of air that insulates the cockroaches from the intense heat of their surroundings. This hairy microclimate also cuts down on the moisture lost while exhaling.

Some of my favorite cockroaches, the Perisphaeriinae, look like pillbugs. (Some even come in bright red and I challenge you not to accept them as adorable.) When something wicked this way comes, these species do the exact opposite of the pancake roaches: they roll up into tiny, impenetrable balls. Not only does this pose protect the insect from the mandibles of ants and other predators, but it seems to provide structural support, giving the roach extra strength to prevent death by crushing.

It gets better. Perisphaeriinae are some of the many, many cockroaches who provide parental care for their young. If anything threatens Momma Perisphaerus and her brood, she can roll up and collect all her nymphs inside her many-legged fortress. There are even snacks to be had! Female roaches in this genus have “four distinct orifices” on their underside that the nymphs can insert their straw-like mouthparts into and collect some sort of nourishing bodily secretion. (We don’t know if the liquid is glandular or blood-based, or what, just that the nymphs’ mouthparts are precisely the same size as the holes.)

If the idea of cockroach “milk” sounds familiar, it’s probably because every website on the Internet was hailing the substance as the next superfood just a few weeks ago. This was mostly an exercise in clickbait, since the scientific paper in question had basically nothing to do with human nutrition—as insect expert Joe Ballenger pointed out on the Ask An Entomologist blog.

“Insects should definitely play a bigger role in food production,” says Ballenger, who works as an entomologist in the agricultural sector. “But I think cockroaches in particular are problematic because of potential allergy issues.” But hey, the whole milk hullabaloo got people talking about roaches, and Ballenger considers that a win.

“For me, personally, I'm fascinated by their social interactions,” he adds. “Cockroaches are not loners. They hang out together, cooperate, and even make decisions with one another. Just like people, it's clear they suffer when they're isolated.”

Certain cockroach species emit alarm pheromones when startled, thereby warning their comrades when danger is near. And studies have shown that groups of cockroaches are more likely to survive extreme dry spells than loners. For instance, individual roaches are enveloped by a thin layer of water vapor that clings to their shells, but it seems cockroach posses can share this force field and conserve water more efficiently.

The American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) can run four times faster than a cheetah—and they can do it on your ceiling. Many species have marvelous, complex folding wings and are surprisingly agile in the air. Plenty more can swim, and some species can even use a tube at the end of their abdomen as a snorkel. Other cockroaches have hairs that trap air bubbles against their bellies, which is basically the insect equivalent of a scuba tank. Desert species do a breaststroke through the sand.

I realize that this is starting to sound like Bubba explaining all the different ways you can prepare shrimp, but the more I learn about cockroaches, the more I want to learn about cockroaches. We haven’t even talked about the infinite nature of the female’s labyrinthine reproductive tract or the evolutionary link between cockroaches and termites. And what of cockroach cuddling and cockroach crunch-force, the roach races at Roachill Downs and cockroach jetpacks?

Schal estimates that there are probably at least another 5,000 cockroach species out there, just waiting to be discovered. Unfortunately, few scientists are devoted to ferreting these majestic creatures out. For some reason, it appears that when graduate students decide what to do with the rest of their lives, most of them would rather specialize in dolphins and grizzly bears and lemurs.

So here's my plea: Scientists of Tomorrow, please go study cockroaches, because I’m not nearly done writing about them. I promise they won't give you gastroenteritis.

*Editor's note, September 1, 2016: An earlier version of this article misstated the percentage of known cockroach species. It is less than 0.5 percent. Additionally, Cryptocercus bores into logs, not the earth.