In Search of the Mysterious Narwhal

Ballerina turned biologist Kristin Laidre gives her all to study the elusive, deep-diving, ice-loving whale known as the “unicorn of the sea”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Narwhals-Arctic-Ocean-631.jpg)

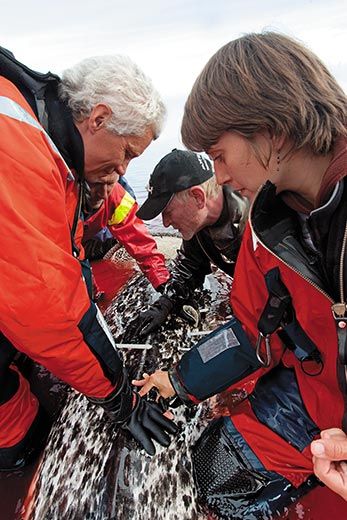

Even before the hunters were off the phone, Kristin Laidre was out of her pajamas and struggling into a survival suit. She ran down to the beach, where a motorboat awaited. The night was frigid with ice-chip stars; the northern lights glowed green overhead. Laidre and a colleague sped past looming bergs and black cliffs plated with ice to the spot offshore where the villagers' boats were circling. The whale was there, a thrashing ton of panic amid the swells. Laidre could see its outline in the water and smell its sour breath.

The scientists and hunters maneuvered boats and began hauling in the nylon net that had been strung from shore and floated with plastic buoys. It was exceptionally heavy because it was soaking wet and, Laidre would recall, "there was a whale in it." Once the mottled black animal was in a secure hammock, they could slip a rope on its tail and a hoop net over its head and float it back to the beach to be measured and tagged.

But something was wrong. The whale seemed to be only partially caught—snagged by the head or tail, Laidre wasn't sure. The hunters screamed at each other, the seas heaved and the boats drifted toward the fierce cliffs. The hunters fought to bring the whale up, and for a moment it seemed as if the animal, a big female, was theirs—Laidre reached out and touched its rubbery skin.

Then the whale went under and the net went limp, and with a sinking heart Laidre shined her pale headlamp into water as dark as oil.

The narwhal was gone.

Kristin Laidre did not set out to wrestle whales in the devastatingly cold waters off Greenland's west coast. She wanted to be a ballerina. Growing up near landlocked Saratoga Springs, New York, where the New York City Ballet spends its summer season, she discovered the choreography of George Balanchine and trained throughout her teens to be an elite dancer. After high school, she danced with the Pacific Northwest Ballet, one of the nation's most competitive companies, and while practicing a grueling 12 hours a day performed in Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella and The Firebird.

Wearing hiking boots instead of toe shoes, she still carries herself with a dancer's grace, a perfect surety of movement that suggests she can execute a plié or stand up to a polar bear with equal competence. Laidre's three-year dance career ended after a foot injury, but she says ballet prepared her rather well for her subsequent incarnation as an arctic biologist and perhaps America's leading expert on narwhals, the shy and retiring cetaceans with the "unicorn horn"—actually a giant tooth—found only in the Greenlandic and Canadian Arctic.

"When you are a ballet dancer you learn how to suffer," Laidre explains. "You learn to be in conditions that aren't ideal, but you persist because you're doing something you love and care about. I have a philosophy that science is art, that there is creativity involved, and devotion. You need artistry to be a scientist."

Like the elusive whale she studies, which follows the spread and retreat of the ice edge, Laidre, 33, has become a migratory creature. After earning undergraduate and doctoral degrees at the University of Washington, she now spends part of her year at its Polar Science Center, and the rest of the time she works with collaborators in Denmark or Greenland, conducting aerial surveys, picking through whale stomachs and setting up house in coastal hunting settlements, where she hires hunters to catch narwhals. Along the way she has learned to speak Danish and rudimentary West Greenlandic.

The Greenlandic phrase she hears most often—whenever the weather blows up or the transmitters malfunction or the whales don't show—is immaqa aqagu. Maybe tomorrow.

That's because she's devoted to what she calls "possibly the worst study animal in the world." Narwhals live in the cracks of dense pack ice for much of the year. They flee from motorboats and helicopters. They can't be herded toward shore like belugas, and because they're small (for whales) and maddeningly fast, it's little use trying to tag them with transmitters shot from air rifles. They must be netted and manhandled, although Laidre is trying a variation on an aboriginal method, attaching transmitters to modified harpoons that hunters toss from stealthy Greenlandic kayaks.

"Narwhals are hopelessly hard to see, never come when you want them to, swimming far offshore and underwater the whole time," she says. "You think you'll catch a whale in three weeks, you probably won't. Whole field seasons go by and you don't even see a narwhal. There are so many disappointments. It takes great patience and optimism—those are my two words."

The species is practically a blank slate, which is what drew her to narwhals in the first place—that and the crystalline allure of the Arctic. By now she has analyzed scores of narwhal carcasses and managed to tag and follow about 40 live animals, publishing new information about diving behavior, migration patterns, relationship to sea ice and reactions to killer whales. Much of what the world knows about the narwhal's picky eating habits comes from Laidre's research, particularly a 2005 study that offered the first evidence of the whales' winter diet, which is heavy in squid, arctic cod and Greenland halibut. She is the co-author of the 2006 book Greenland's Winter Whales.

Basic questions drive her work. How many narwhals are there? Where do they travel and why? Greenland's government funds part of her expeditions, and her findings influence how the narwhal hunting season is managed. As Greenland modernizes, Laidre hopes to raise public awareness about the whales and their significance to the people and environment of the north. Especially now that the climate seems to be warming, narwhals, Laidre believes, will be seriously affected by melting.

"Most creatures on earth we know a lot more about," Laidre says. "We probably know a lot more about the brains of grasshoppers than we do about narwhals."

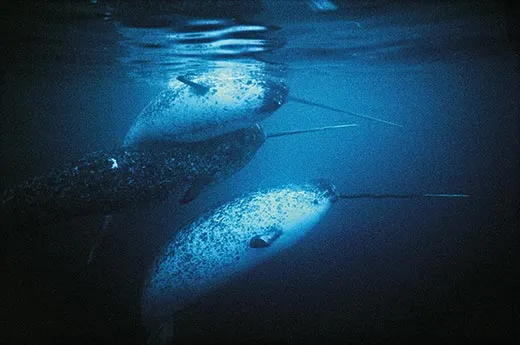

The alabaster beluga's dark cousin, the narwhal is not a conventionally beautiful animal. Its unlovely name means "corpse whale," because its splotchy flesh reminded Norse sailors of a drowned body. This speckled complexion is "weird," says James Mead, curator of marine mammals at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History (NMNH); usually, he says, whales are a more uniform color. And unlike other whales, narwhals—which can live more than 100 years—die shortly in captivity, greatly reducing the opportunity to study them. "We've only had a glimpse of the beast," Pierre Richard, a prominent Canadian narwhal specialist, told me.

The whales mate in cracks of ice in the dead of winter, in pitch darkness, when the wind chill can drive the air temperature to minus 60 degrees Fahrenheit. ("Not very romantic," Richard notes.) While shifting currents and winds create breaks in the ice, enabling the animals to surface and breathe, the whales must keep moving to avoid getting trapped. Because of the extreme cold, calves are born husky, about one-third the size of their 12-foot-long, 2,000-pound mothers. Like belugas and bowheads, which also inhabit arctic waters, narwhals are about 50 percent body fat; other whales are closer to 20 or 30 percent. No one has ever seen a submerged narwhal eat. Laidre led a study of the stomach contents of 121 narwhals that suggested they fast in summer and gorge on fish in winter.

Fond of bottom-dwelling prey like Greenland halibut, narwhals are incredibly deep divers. When Mads Peter Heide-Jorgensen, Laidre's Danish colleague and frequent collaborator, pioneered narwhal-tagging techniques in the early 1990s, his transmitters kept breaking under the water pressure. Five hundred meters, 1,000, 1,500—the whales, which have compressible rib cages, kept plunging. They bottomed out around 1,800 meters—more than a mile deep. At such depths, the whales apparently swim upside down much of the time.

The whales' most dazzling feature, of course, is the swizzle-stick tusk that sprouts from their upper left jaw. Though the whales' scientific name is Monodon monoceros, "one tooth, one horn," an occasional male has two tusks (the NMNH has two rare specimens) and only 3 percent of females have a tusk at all. The solitary fang, which is filled with dental pulp and nerves like an ordinary tooth, can grow thick as a lamppost and taller than a man, and it has a twist. On living whales, it's typically green with algae and alive with sea lice at its base. No one's sure precisely how or why it evolved—it has been called a weapon, an ice pick, a kind of dousing rod for fertile females, a sensor of water temperature and salinity, and a lure for prey. Herman Melville joked that it was a letter opener.

"Everybody has a theory on this," Laidre says with a sigh. (The question comes up a lot at cocktail parties.)

Most scientists, Laidre included, side with Charles Darwin, who speculated in The Descent of Man that the ivory lance was a secondary sex characteristic, like a moose's antlers, useful in establishing dominance hierarchies. Males have been observed gently jousting with their teeth—the scientific term is "tusking"—when females are nearby. The tooth, Laidre patiently explains, cannot be essential because most females survive without one.

In 2004, Greenland set narwhal-hunting quotas for the first time, despite some hunters' protests, and banned the export of the tusks, halting a thousand-year-old trade. Conservationists—newly roiled this past summer by the discovery of dozens of dead narwhals in East Greenland, the tusks chopped out of the skulls and the meat left to rot—want still more restrictions. It's estimated there are at least 80,000 of the animals, but nobody knows for sure. The International Union for Conservation of Nature this year said the species was "near threatened."

To track the whales, Laidre and Heide-Jorgensen have collaborated with hunters on Greenland's west coast and were just starting to build relationships in the village of Niaqornat when I asked to tag along. We would arrive in late October and the scientists would remain through mid-November, as darkness descended and the ice glided into the fjords, and the pods of whales, which they suspect summer in Melville Bay several hundred miles north, made their way south. It was a time frame that some of Laidre's colleagues in Seattle, many of them climate scientists who prefer to study the Arctic via buoy and robotic plane, considered vaguely insane.

Laidre, of course, was optimistic.

When Laidre, Heide-Jorgensen and I first reached the village, after a two-hour boat ride that involved rounding icebergs in the inky blackness of a late arctic afternoon, the sled dogs greeted us like hysterical fans at a rock concert while villagers crowded the boat, reaching in to pull out our luggage and hollering at Laidre in Greenlandic.

Niaqornat ( pop. 60) is on a tongue of land in Baffin Bay inside the Arctic Circle. The settlement sits hard against a white wall of mountains, where men hunting arctic grouse leave tiny red droplets in their footsteps on the slopes: blackberries crushed under the snow. Greenland has its own home-rule government but remains a Danish possession, and thanks to the Danish influence the town is fully wired, with personal computers glowing like hearths in almost every living room. But none of the houses, including the drafty three-room field station used by Laidre and other scientists, has plumbing or running water; the kerosene stoves that keep the water from freezing are easily puffed out by the ripping wind, which also brings waves bashing against the town's scrap of black beach.

With its tide line of pulverized ice crystals, the beach is the chaotic center of village life, scattered with oil drums, anchors and the hunters' little open boats, some of which are decorated with arctic fox tails like lucky giant rabbit's feet. There are waterfront drying racks hung with seal ribs, waxen-looking strips of shark and other fish, and the occasional musk ox head masked with ice. Throughout the town, sled dogs are staked to the frozen ground; there are at least three times as many dogs as people.

Signs of narwhals are everywhere, especially now that the tusk market has been shut down and hunters can't sell the ivory for gas money and other expenses. The whales' undeveloped inner teeth are strung up over front porches like clothespins on a line. A thick tooth is proudly mounted on the wall of the little building that serves as the town hall, school, library and church (complete with sealskin kneelers). It seems the fashion to lean a big tusk across a house's front window.

"There are months when no supplies are coming into the town, and people depend only on what they pull out of the sea," Laidre told me. "The arrival of these whales is a small window of opportunity, and hunters have to have an extremely deep knowledge of how they behave."

The narwhals typically arrive in November, darting into the fjord in pursuit of gonatus squid, and Niaqornat men in motorboats shoot the animals with rifles. But in the springtime, when the whales pass by again on their way north, the hunters work in the old way, driving their dog sleds out into the ice-covered fjord. Then they creep in single file, wearing sealskin boots so as not to make a sound—even a clenched toe can make the ice creak. They get as close as they can to the surfacing whales, then hurl their harpoons.

In the darkness they can tell the difference between a beluga and a narwhal by the sound of their breathing. And if the hunters can't hear anything, they search them out by smell. "They smell like blubber," a young man told me.

During the Middle Ages, and even earlier, narwhal tusk was sold in Europe and the Far East as unicorn horn. Physicians believed that powdered unicorn horn could cure ills from plague to rabies and even raise the dead. It seems also to have been marketed as a precursor to Viagra, and it rivaled snake's tongue and griffin's claw as a detector of poison. Since poisonings were all the rage in medieval times, "unicorn horn" became one of the most coveted substances in Europe, worth ten times its weight in gold. French monarchs dined with narwhal-tooth utensils; Martin Luther was fed powdered tusk as medicine before he died. The ivory spiral was used to make the scepter of the Hapsburgs, Ivan the Terrible's staff, the sword of Charles the Bold.

Historians have not definitively identified where the ancient tusks originated, though one theory is that the narwhals were harvested in the Siberian Arctic (where, for unknown reasons, they no longer live). But in the late 900s the Vikings happened upon Greenland, swarming with narwhals, their teeth more precious than polar bear pelts and the live falcons they could hawk to Arabian princes. Norse longboats rowed north in pursuit of the toothed whales, braving summer storms to trade with the Skraelings, as the Vikings called the Inuit, whom they despised.

It was Laidre's intellectual ancestors, the Enlightenment scientists, who ruined the racket. In 1638, the Danish scholar Ole Wurm refuted the unicorn myth, showing that the prized horn material came from narwhals, and others followed suit. In 1746, faced with mounting evidence, British physicians abruptly stopped prescribing the horn as a wonder drug (though the Apothecaries' Society of London had already incorporated unicorns into its coat of arms). Today, the tusks fetch more humble prices—about $1,700 a foot at a 2007 auction in Beverly Hills. (It has been illegal to import narwhal tusk into the United States since the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, but material known to have entered the nation earlier can be bought and sold.)

To the Inuit, the whale and its horn are hardly luxury goods. Greenlanders traditionally used every part of the animal, burning its blubber in lamps, using the back sinews to sew boots and clothes and the skin for dog sled traces. The tusks were tools of survival in a treeless landscape, used as sled runners, tent poles and harpoons. The tusks were also bleached and sold whole or carved into figurines (and, yes, Mr. Melville, letter openers). Even today, when iPods are sold at the Niaqornat village store, narwhals remain a vital source of food. Narwhal meat feeds dogs and fills freezers for the winter, a last nutritional opportunity before total darkness closes over the town like a fist. Mattak, the layer of skin and blubber that is eaten raw and rumored to taste like hazelnuts, is an Inuit delicacy.

When an animal is killed, word spreads by radio, and the whole town rushes down to the beach, shouting the hunter's name. After the butchering, families share the carcass, part of a traditional gifting system now almost unknown outside the settlements. "We make a living only because the whales come," Karl-Kristian Kruse, a young hunter, told me. "If narwhals didn't come, there would be nothing here."

The new whale quotas will probably make life more difficult in Niaqornat: before 2004, there were no limits on the number of narwhals hunters could catch, but in 2008 the whole village was allotted only six. "The scientists want to know how many whales there are," Anthon Moller, a 25-year-old hunter, said bitterly. "Well, there are a lot, more than ever before. With quotas it's hard to live."

When Laidre and Heide-Jorgensen first showed up to ask for help catching narwhals in nets and then—of all preposterous notions—letting them go, some men thought it was folly, even though the scientists would pay almost as handsomely as the Vikings. Now, two years later, having lost one whale after netting it and successfully tagging only one other, the hunters still weren't entirely persuaded. And yet, they were curious. They, too, wanted to know where the whales went.

There are no doorbells in Niaqornat, and no knocking. When the town's dozen or so hunters came over to the scientists' house, they just walked in, stomping their big boots politely, to give fair warning as much as to kick off the snow.

They were small, spare men, smelling of fish and wet flannel, with wind-burned skin, flared nostrils and dark eyes. Laidre offered coffee, along with a cake she'd baked that afternoon. They munched watchfully, some of them humming to themselves, while Heide-Jorgensen showed slides of the narwhal tagged in 2007, captured when Laidre was home in Seattle. To catch a unicorn, it is said, you need virgins for bait; to net a narwhal, and transfer it from ocean to beach and back again, a bunkhouse of cowboys would be handier. The whale bucked like a bronco as the hunters, led by one of Laidre's technicians, pinned a transmitter, about the size of a bar of soap, to the dorsal ridge. When at last the tag was secure, the technician was so relieved he smooched the animal's broad back. Then they walked it out with the tide and let it go. One of the hunters had videotaped the entire frothy episode on his cellphone; a year later, the villagers still watched it raptly.

"Kusanaq," Heide-Jorgensen told the hunters. "Beautiful. A great collaboration. This time we'll move the tag back a little and also put on a tusk transmitter."

He explained that he and Laidre would pay: 20,000 Danish kroner, or about $3,700, for a captured beluga, which the scientists were also studying; $4,500 for a qernertaq, or narwhal; $5,500 for a qernertaq tuugaalik, or tusked narwhal (hunters expect more for males because they're accustomed to selling the tusks); and $6,400 for an angisoq tuugaaq, or large tusked narwhal.

The hunters thought this over for a moment, then one raised his hand with a question: What would happen if the whale died?

In that case, the scientists explained, the meat would be divided equally among the villagers.

The scientists also screened a map of the tagged narwhal's travels, its movements traced in green. The whales can migrate more than 1,000 miles in a year. After leaving Niaqornat this one had wandered farther into the fjord in December and January, near Uummannaq, a bigger town with bars and restaurants, where many of the hunters had friends and rivals. Then in March it had turned north toward its summering grounds near Melville Bay, at which point the transmitter stopped working. The hunters eyed the crazy green zigzag with fascination. Though some had seen the data before in weekly e-mail updates from the scientists, it was still astonishing stuff. Some later said they'd enjoy daily updates: they wanted to track the narwhal like traders follow the stock market. When the hunters finally left, full of coffee, cake and respectful criticisms of Laidre's baking, the matter was decided. They would set nets in the morning.

Well, immaqa aqagu.

That evening, the temperature, which had sometimes reached the balmy 40s during the day—"Beluga weather," Heide-Jorgensen had said a bit contemptuously—plunged into the teens. Even inside the house, the cold was devouring. All night the wind whooped and the dogs sang and the waves bludgeoned the shore. By morning the dogs had curled into miserable little doughnuts in the snow. The hunters dragged their boats to higher ground. On the hills above town much of the snow had blown away, giving the black earth a dappled appearance, like narwhal skin. No nets would be set today, nor—if the weather report was accurate—for days to come.

"No nets and no underwear," said Laidre, whose personal field gear was due to arrive on a helicopter that almost certainly wouldn't show. "Life is not easy."

At times like these she almost envied colleagues who studied microscopic organisms in jars instead of whales in the raging North Atlantic. Her own brother, a graduate student at Princeton, was researching hermit crabs on the beaches of Ireland, where a cozy pub was never far away. Meanwhile, in Niaqornat, the wind was so vicious that Heide-Jorgensen got trapped in the community bathhouse for hours. The scientists took to singing the Merle Haggard song "If We Make It Through December." For days they made spreadsheets, calibrated transmitters, charged their headlamps—anything to keep busy.

There was some excitement when a young hunter, having learned that I had passed my whole life never having tasted narwhal mattak, arrived with a frozen piece from last year's harvest. (I had asked him what it tasted like, and he said, with a pitying gaze, "Mattak is mattak.") Hazelnut was not the flavor that came to my mind. But Laidre and Heide-Jorgensen tucked away great mouthfuls of the stuff, dipped in soy sauce. In the old days, foreign sailors who abstained from vitamin-C-rich whale mattak sometimes died of scurvy.

Several Niaqornat men who'd been out hunting belugas before the storm were stranded a few hundred miles away, but no one in town expressed concern; in fact, everyone seemed quite merry. Winter's arrival is good news on this part of Greenland's coast, because narwhals always follow the freeze.

The whales' fate is tied to the ice. Narwhal fossils have been found as far south as Norfolk, England, to which the ice cover extended 50,000 years ago. Ice protects narwhals from the orcas that sometimes attack their pods; the killer whales' high, stiff dorsal fins, which are like fearsome black pirate sails, prevent them from entering frozen waters. Even more important, Laidre says, narwhals beneath the pane of ice enjoy almost exclusive access to prey—particularly Greenlandic halibut, which may be why they are such gluttons in winter.

Occupying an icy world has its risks. Narwhals lingering too long in the fjords sometimes get trapped as the ice expands and the cracks shrink; they cut themselves horribly trying to breathe. In Canada this past fall, some 600 narwhals were stranded this way, doomed to drown before hunters killed them. These entrapments are called savssats, a derivative of an Inuit word meaning "to bar his way." Laidre believes that massive die-offs in savssats thousands of years ago may account for the narwhal's extraordinarily low genetic diversity.

Still, less ice could spell disaster for narwhals. Since 1979, the Arctic has lost an ice mass the size of nearly two Alaskas, and last summer saw the second-lowest ice cover on record (surpassed only by 2007). So far the water has opened mostly north of Greenland, but hunters in Niaqornat say they've noticed differences in the way their fjord freezes. Even if warming trends are somehow reversed, Laidre's polar-expert colleagues back in Seattle doubt that the ice will ever regain its former coverage area and thickness. Narwhals may be imperiled because of their genetic homogeneity, limited diet and fixed migration patterns. Laidre was the lead author of an influential paper in the journal Ecological Applications that ranked narwhals, along with polar bears and hooded seals, as the arctic species most vulnerable to climate change.

"These whales spend half the year in dense ice," she says. "As the ice's structure and timing changes, the whole oceanography, the plankton ecology, changes, and that affects their prey. Narwhals are a specialist species. Changes in the environment affect them—without a doubt—because they are not flexible."

For the past several years Laidre has been attaching temperature sensors along with tracking gear to captured narwhals. One morning in Niaqornat, she received an e-mail with an analysis of water temperature data collected by 15 tagged narwhals from 2005 to 2007. Compared with historical information from icebreakers, the readings showed warming of a degree or more in the depths of Baffin Bay. Laidre was ecstatic that her collecting method seemed to have worked, though the implications of rising temperatures were disturbing.

Indeed, there are already reports of more killer whales in the Arctic.

Once the gales stopped, it was cold but calm: perfect narwhal weather, Heide-Jorgensen declared. I sailed out to set nets with a hunter, Hans Lovstrom, whose boat kept pace with the kittiwakes, pretty gray-winged gulls. We knotted the rope with bare fingers; mine soon became too cold to move. Lovstrom told me to plunge my hands into the water, then rub them vigorously together. I pretended it helped.

Back in the village, social invitations began to flow into the scientists' little house. Would they like to come to a coffee party? A supper of seal soup? Youth night at the school? The colder the weather, the more the community seemed to warm to the scientists. The first time Laidre and Heide-Jorgensen spent a field season in Niaqornat, the village happened to hold a dance party. Someone strummed an electric guitar. Laidre danced with all the hunters, swooping through the steps of the Greenlandic polka, which European whalers had taught the Inuit centuries ago.

That's what everyone had been hollering about when we'd arrived at Niaqornat the first night—they remembered, and admired, the dancing scientist.

As long as the whales keep coming, maybe Greenland's hunting settlements won't be completely absorbed into the growing tourism culture that rents out aluminum igloos to rich foreigners and pays elite hunters to wear polar bear pants in the summertime and toss harpoons for show.

The Sunday before I left Greenland (Laidre would stay for several more weeks), the stranded beluga hunters chugged back to Niaqornat in their boat. Just before darkness fell, people made their way down to the water. Bundled-up babies were lifted high overhead for a better view; older children were ruddy with excitement, because beluga mattak is second only to the narwhal's as winter fare. The dogs yelped as the yellow boat, laminated with ice, pulled into the dock.

Bashful before so many eyes but stealing proud looks at their wives, the hunters spread tarps and then tossed out sections of beluga spine and huge, quivering organs, which landed with a slap on the dock. Last of all came the beluga mattak, folded in bags, like fluffy white towels. The dismembered whales were loaded into wheelbarrows and spirited away; there would be great feasting that night on beluga, which, like narwhal meat, is nearly black because of all the oxygen-binding myoglobin in the muscle. It would be boiled and served with generous crescents of blubber. The scientists would be guests of honor.

"When I'm old and in a nursing home, I'll think of the friends I have in the Arctic as much as my experiences with whales," Laidre had told me. "And I'm happy that my work helps protect a resource that's so important to their lives."

The hunters had good news, too. Hundreds of miles north, in the endless blackness of ocean and near-permanent night, they had crossed paths with a pod of narwhals, perhaps the first of the season, making their way south toward the fjord.

Abigail Tucker is the magazine's staff writer.