Is the Can Worse Than the Soda? Study Finds Correlation Between BPA and Obesity

BPA, a chemical used in aluminum soda cans and other food packaging, was found to be associated with childhood obesity in a new study

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120918090045soda-can-small.jpg)

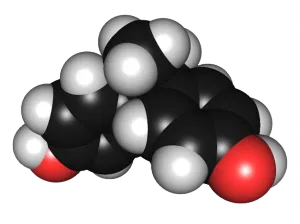

Since the 1960s, manufacturers have widely used the chemical bisphenol-A (BPA) in plastics and food packaging. Only recently, though, have scientists begun thoroughly looking into how the compound might affect human health—and what they’ve found has been a cause for concern.

Starting in 2006, a series of studies, mostly in mice, indicated that the chemical might act as an endocrine disruptor (by mimicking the hormone estrogen), cause problems during development and potentially affect the reproductive system, reducing fertility. After a 2010 Food and Drug Administration report warned that the compound could pose an especially hazardous risk for fetuses, infants and young children, BPA-free water bottles and food containers started flying off the shelves. In July, the FDA banned the use of BPA in baby bottles and sippy cups, but the chemical is still present in aluminum cans, containers of baby formula and other packaging materials.

Now comes another piece of data on a potential risk from BPA but in an area of health in which it has largely been overlooked: obesity. A study by researchers from New York University, published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association, looked at a sample of nearly 3,000 children and teens across the country and found a “significant” link between the amount of BPA in their urine and the prevalence of obesity.

“This is the first association of an environmental chemical in childhood obesity in a large, nationally representative sample,” said lead investigator Leonardo Trasande, who studies the role of environmental factors in childhood disease at NYU. “We note the recent FDA ban of BPA in baby bottles and sippy cups, yet our findings raise questions about exposure to BPA in consumer products used by older children.”

The researchers pulled data from the 2003 to 2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, and after controlling for differences in ethnicity, age, caregiver education, income level, sex, caloric intake, television viewing habits and other factors, they found that children and adolescents with the highest levels of BPA in their urine had a 2.6 times greater chance of being obese than those with the lowest levels. Overall, 22.3 percent of those in the quartile with the highest levels of BPA were obese, compared with just 10.3 percent of those in the quartile with the lowest levels of BPA.

The vast majority of BPA in our bodies comes from ingestion of contaminated food and water. The compound is often used as an internal barrier in food packaging, so that the product we eat or drink does not come into direct contact with a metal can or plastic container. When heated or washed, though, plastics containing BPA can break down and release the chemical into the food or liquid they hold. As a result, roughly 93 percent of the U.S. population has detectable levels of BPA in their urine.

The researchers point specifically to the continuing presence of BPA in aluminum cans as a major problem. “Most people agree the majority of BPA exposure in the United States comes from aluminum cans,” Trasande said. “Removing it from aluminum cans is probably one of the best ways we can limit exposure. There are alternatives that manufacturers can use to line aluminum cans.”

The finding is only a correlation between the amount of BPA in the body and obesity, rather than evidence that one causes the other. Nevertheless, the researchers speculate on a possible underlying mechanism, alluding to other studies that have shown that during development the chemical may disrupt several different mechanisms of human metabolism in ways that increase body mass. They also note studies that have revealed associations between urinary levels of BPA and incidences of adult diabetes, cardiovascular disease and abnormal liver function.

Like previous findings on the role of gastrointestinal bacteria in increasing fat intake, this study hints at the surprisingly complex root causes of obesity, once thought to simply reflect an imbalance between caloric intake and exercise. “Our findings further demonstrate the need for a broader paradigm in the way we think about the obesity epidemic,” said Trasande. “Unhealthy diet and lack of physical activity certainly contribute to increased fat mass, but the story clearly doesn’t end there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)