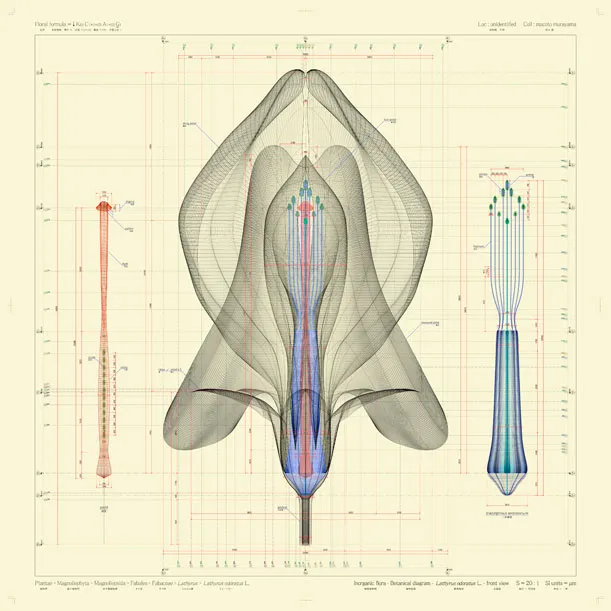

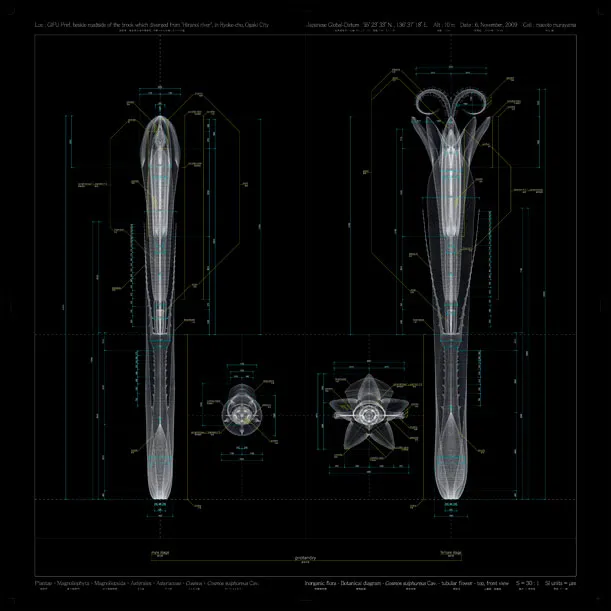

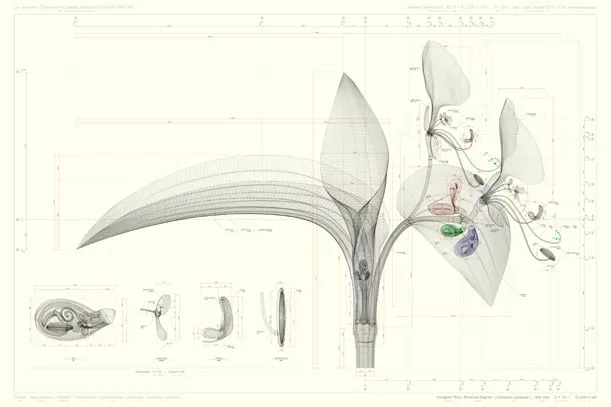

Macoto Murayama’s Intricate Blueprints of Flowers

The Japanese artist depicts blossoms from various plant species in fastidious detail

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/07/4107f852-9abe-4c4b-861e-a9e6d1b4e9e6/macoto-murayama-lathyrus-odoratus-side-view.jpg)

The worlds of architecture and scientific illustration collided when Macoto Murayama was studying at Miyagi University in Japan. The two have a great deal in common, as far as the artist’s eye could see; both architectural plans and scientific illustrations are, as he puts it, “explanatory figures” with meticulous attention paid to detail. “An image of a thing presented with massive and various information is not just visually beautiful, it is also possible to catch an elaborate operation involved in the process of construction of this thing,” Murayama once said in an interview.

In a project he calls “Inorganic flora,” the 29-year-old Japanese artist diagrams flowers. He buys his specimens—sweetpeas (Lathyrus odoratus L. , Asiatic dayflowers (Commelina communis L.) and sulfur cosmos (Cosmos sulphureus Cav.), to name a few—from flower stands or collects them from the roadside. Murayama carefully dissects each flower, removing its petals, anther, stigma and ovaries with a scalpel. He studies the separate parts of the flower under a magnifying glass and then sketches and photographs them.

Using 3D computer graphics software, the artist then creates models of the full blossom as well as of the stigma, sepals and other parts of the bloom. He cleans up his composition in Photoshop and adds measurements and annotations in Illustrator, so that in the end, he has created nothing short of a botanical blueprint.

“The transparency of this work refers not only to the lucid petals of a flower, but to the ambitious, romantic and utopian struggle of science to see and present the world as transparent (completely seen, entirely grasped) object,” says Frantic Gallery, the Tokyo establishment that represents the artist, on its Web site.

Murayama chose flowers as his subject because they have interesting shapes and, unlike traditional architectural structures, they are organic. But, as he has said in an interview, “When I looked closer into a plant that I thought was organic, I found in its form and inner structure hidden mechanical and inorganic elements.” After dissecting it, he added, “My perception of a flower was completely changed.”

His approach makes sense when you hear who Murayama counts among his influences—Yoshihiro Inomoto, a celebrated automotive illustrator, and Tomitaro Makino, an esteemed botanist and scientific illustrator.

Spoon & Tamago, a blog on Japanese design, says that the illustrations “look like they belong in a manual for semiconductors.” Certainly, by portraying his specimens in a manner that resembles blueprints, Murayama makes flowers, with all their intricacies, look like something human-made, something engineered.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)