Man-Eaters of Tsavo

They are perhaps the world’s most notorious wild lions. Their ancestors were vilified more than 100 years ago as the man-eaters of Tsavo

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Colonel-Patterson-first-Tsavo-Lion-631.jpg)

They are perhaps the world’s most notorious wild lions. Their ancestors were vilified more than 100 years ago as the man-eaters of Tsavo, a vast swath of Kenya savanna around the Tsavo River.

Bruce Patterson has spent the past decade studying lions in the Tsavo region, and for several nights I went into the bush with him and a team of volunteers, hoping to glimpse one of the beasts.

We headed out in a truck along narrow red dirt trails through thick scrub. A spotlight threw a slender beam through the darkness. Kudus, huge antelopes with curved horns, skittered away. A herd of elephants passed, their massive bodies silhouetted in the dark.

One evening just after midnight, we came upon three lions resting by a water hole. Patterson identified them as a 4-year-old male he has named Dickens and two unnamed females. The three lions rose and Dickens led the two females into the scrub.

On such forays Patterson has come to better understand the Tsavo lions. Their prides, with up to 10 females and just 1 male, are smaller than Serengeti lion prides, which have up to 20 females and 2 or more males. In Tsavo, male lions do not share power with other males.

Tsavo males look different as well. The most vigorous Serengeti males sport large dark manes, while in Tsavo they have short, thin manes or none at all. “It’s all about water,” Patterson says. Tsavo is hotter and drier than the Serengeti, and a male with a heavy mane “would squander his daily water allowance simply panting under a bush, with none to spare for patrolling his territory, hunting or finding mates.”

But it’s the lions’ reputation for preying on people that attracts attention. “For centuries Arab slave caravans passed through Tsavo on the way to Mombasa,” said Samuel Kasiki, deputy director of Biodiversity Research and Monitoring with the Kenya Wildlife Service. “The death rate was high; it was a bad area for sleeping sickness from the tsetse fly; and the bodies of slaves who died or were dying were left where they dropped. So the lions may have gotten their taste for human flesh by eating the corpses.”

In 1898, two lions terrorized crews constructing a railroad bridge over the Tsavo River, killing—according to some estimates—135 people. “Hundreds of men fell victims to these savage creatures, whose very jaws were steeped in blood,” wrote a worker on the railway, a project of the British colonial government. “Bones, flesh, skin and blood, they devoured all, and left not a trace behind them.”

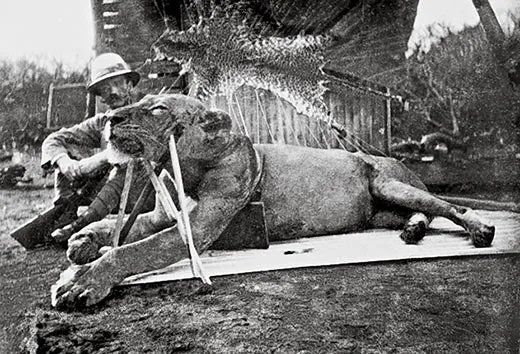

Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson shot the lions (a 1996 movie, The Ghost and the Darkness, dramatized the story) and sold their bodies for $5,000 to the Field Museum in Chicago, where, stuffed, they greet visitors to this day.

Bruce Patterson (no relation to John), a zoologist with the museum, continues to study those animals. Chemical tests of hair samples recently confirmed that the lions had eaten human flesh in the months before they were killed. Patterson and his colleagues estimate that one lion ate 10 people, and the other about 24—far fewer than the legendary 135 victims, but still horrifying.

When I arrived in Nairobi, word reached the capital that a lion had just killed a woman at Tsavo. A cattle herder had been devoured weeks earlier. “That’s not unusual at Tsavo,” Kasiki said.

Still, today’s Tsavo lions are not innately more bloodthirsty than other lions, Patterson says; they attack people for the same reason their forebears did a century ago: “our encroachment into what was once the territory of lions.” Injured lions are especially dangerous. One of the original man-eaters had severe dental disease that would have made him a poor hunter, Patterson found. Such lions may learn to attack people rather than game, he says, “because we are slower, weaker and more defenseless.”

Paul Raffaele’s book Among the Great Apes will be published in February.