Meet Lucy Jones, “the Earthquake Lady”

As part of her plan to prepare Americans for the next “big one,” the seismologist tackles the dangerous phenomenon of denial

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Profile-Lucy-Jones-seismologist-631.jpg)

One of Lucy Jones’ first memories is of an earthquake. It struck north of Los Angeles, not far from her family home in Ventura, and as the ground lurched, her mother guided 2-year-old Lucy and her older brother and sister into a hallway and shielded them with her body. Add that her great-great-grandparents are buried literally in the San Andreas fault and it’s hard not to think that her fate was preordained.

Today Jones is among the world’s most influential seismologists—and perhaps the most recognizable. Her file cabinets bulge with fan letters, among them at least one marriage proposal. “The Earthquake Lady,” she’s called. A science adviser for the U.S. Geological Survey in Pasadena, Jones, 57, is an expert on foreshocks, having authored or co-authored 90 research papers, including the first to use statistical analysis to predict the likelihood that any given temblor will be followed by a bigger one.That research has been the basis for 11 earthquake advisories issued by the state of California since 1985.

Charged with improving the nation’s response to natural disaster, Jones’ specialty, increasingly, is another complex natural phenomenon: denial, that dangerous unwillingness to acknowledge the inevitable. What good is scientific knowledge, in other words, if people don’t respond to it?

You might have caught her on TV trying to help people understand earthquake risks after the Eastern Seaboard felt the 5.8 quake epicentered in Virginia this past August or after Tohoku, Japan, kept rocking and rolling after the 9.0 quake there last March. “She has the bearing of your terrific next-door neighbor who takes superb care of her window boxes. And yet she is as learned as anyone in the field,” says “NBC Nightly News” anchor Brian Williams, who has interviewed Jones numerous times on television.

“I’m everybody’s mother,” she likes to joke, aware that her gender—while not an asset when she was at MIT in the ’70s—is now a plus. “Women are more reassuring after an event,” she says, recalling how moved people were years back when she conducted post-quake TV interviews holding Niels, her 1-year-old son, in her arms (he’s 21 now). That mother-and-child tableau cemented her position as the informed voice of calm in truly unsettling times.

“Lucy brings magnetism to what is normally a dull subject: preparedness,” says Paul Schulz, CEO of the American Red Cross of Greater Los Angeles, whom Jones recently accompanied to Chile to study the impact of its 8.8 magnitude quake in 2010. On that trip, thousands of miles from home, a woman approached Jones and asked for her autograph.

Earthquakes may be classified as foreshocks, mainshocks and aftershocks. All occur when energy in the earth’s crust is released suddenly, forcing tectonic plates to shift. What differentiates them is their relation to each other in space and time. A foreshock is only a foreshock if it happens to occur before a bigger quake on the same fault system. An aftershock occurs after a bigger quake.

A lot of people had pondered foreshocks before Jones did, but she asked a critical question: After an earthquake, is there a statistical method to predict the chances that it was a precursor to a larger jolt? The answer was yes, as Jones demonstrated in a 1985 paper and subsequent studies analyzing every quake in the region’s recorded history. She found that the probability that an earthquake will trigger a bigger one does not depend on the magnitude of the first earthquake but instead is related to its location and interaction with fault systems.

The southern San Andreas ruptures and releases energy on average every 150 years. The last time was more than 300 years ago, which means that Los Angeles and environs may be overdue for a major quake. There’s no way to predict precisely when California’s next “big one” will come, Jones says (or even that it will occur on the San Andreas), but people need to get ready, as was made painfully clear in a massive 2008 study Jones led.

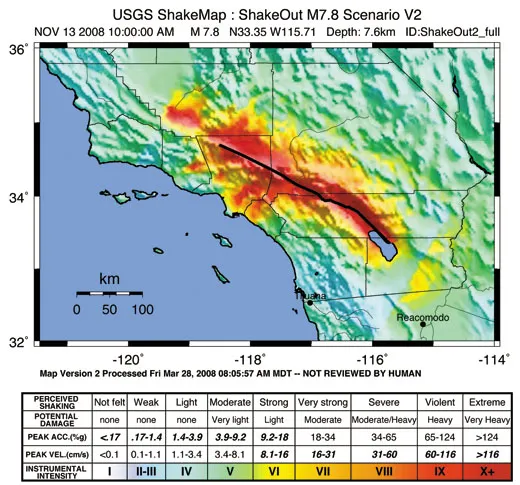

More than 300 scientists and other experts took part in drafting the 308-page ShakeOut Earthquake Scenario. Geologists determined which section of the San Andreas was most likely to blow, and conceived of a 7.8 magnitude tremor. They posited 55 seconds of strong shaking in downtown L.A.—more than seven times the duration of the last big L.A.-area temblor, the 1994 Northridge quake, a magnitude 6.7 generated along a previously unknown fault. There would be landslides and liquefaction and massive damage to roads, rail lines, water conveyance tunnels and aqueducts, electrical and natural gas lines, and telecommunications cables.

If no additional actions are taken to mitigate damage before such a quake hits the nation’s second-largest city, about 2,000 people will die, 50,000 people will be injured, and property and infrastructure disruption will cost about $200 billion to repair, the report said. Perhaps five high-rise buildings will collapse. Some 8,000 buildings and houses of unreinforced concrete will collapse, though retrofitting has already helped reduce the likely loss of life. Households will be without water and power for months.

It all sounds pretty bleak. And yet parts of the report indicate something hopeful, Jones says while sitting on a couch in her office on the California Institute of Technology campus: Better science can save lives (and money). For example, the ShakeOut Scenario estimated that on the day of the quake, 1,600 fires will be large enough to warrant a 911 call. But some will start small, meaning that if residents keep fire extinguishers at the ready and know how to use them, much damage can be avoided. Similarly, 95 percent of those rescued will be aided not by emergency response teams but by friends and neighbors. So if people can be persuaded now to make their homes and offices safe (retrofit unreinforced masonry, attach heavy bookshelves to the wall to keep them from toppling), they’ll be in a better position to aid others. “The earthquake is inevitable and disruption is inevitable,” Jones says, her shoes off and her bare feet tucked underneath her, “but the damage doesn’t have to be.”

Millions of Californians have participated in earthquake drills designed by Jones’ office to teach people how to cope in crisis. (Don’t run outside; do drop, cover and hold on.) Nevada, Oregon and Idaho have done their own versions of the ShakeOut drill, as has the Midwest, where last April the event was timed to the 200th anniversary of a series of quakes around New Madrid, Missouri, still the most powerful temblors east of the Rockies.

“A magnitude 7 quake happens somewhere in the world every month,” Jones says, “a magnitude 6 happens every week.” Many occur in remote or uninhabited regions or under the sea.We pay attention to a disaster like the one that struck New Zealand last year—a 6.3 earthquake near Christchurch that killed 181 people—because, Jones says, it “just happened to be near people. But the earth doesn’t care about that.”

A fourth-generation Southern Californian, Jones grew up in the ’50s and ’60s, when girls were not typically encouraged to excel in math and science. But her father, an aerospace engineer at TRW, who worked on the first lunar module descent engine, taught his daughter to calculate prime numbers when she was 8 years old. Jones got a perfect score on a high-school science aptitude test. A guidance counselor accused her of cheating. “Girls don’t get those kind of scores,” the counselor said.

Despite a math teacher’s suggestion that she attend Harvard University “because they had a better class of men to marry,” she chose Brown, where she studied physics and Chinese and did not take a geology class until her senior year. She was transfixed, devouring the 900-page textbook in a week. Graduating with a B.A. in Chinese language and literature (she studied earthquake references in ancient Chinese texts), Jones went to MIT to get a doctorate in geophysics—one of just two women at the school pursuing an advanced degree in that subject. (And she found time to master the viola de gamba, a Baroque, cello-like instrument that she still plays today.) A few years after the 1975 Haicheng earthquake in Liaoning, China, an adviser said, “Why don’t you start studying foreshocks, and then if China ever opens up, we’ll be in a position to send you to go study there.” In February 1979, while still in grad school, Jones became one of the first U.S. scientists to enter China after Westerners were allowed in. She was 24.

Earthquakes would take her around the world—Afghanistan, New Zealand, Japan—and introduce her to the Iceland-born seismologist Egill Hauksson, a Caltech researcher. The two have been married for 30 years and have two grown sons.

In 2005, she had to choose between continuing her geophysics research and taking the helm of a new project that she helped organize after Hurricane Katrina. “OK, I’m 50,” she recalls thinking. “I’ve got 15 years left in my career. If I go back to research science, maybe I’ll write 30 more papers, of which five will be read and two will matter. And that would be doing pretty good.” By contrast, if she opted to work in the new field of hazard science, using her familiar face and no-nonsense demeanor to change people’s behavior, she realized, “I knew who would write those papers instead of me.” (They have in fact been written.) “It was a question of what mattered to me at that stage in my life. Did I want to get that one more level of academic achievement, or did I want to try and get the science used?”

Of course she chose the latter, and since this past October has served as science adviser for risk reduction at the USGS, working on a project to establish steps that people nationwide can take to minimize damage from all natural hazards.

One morning not long ago, when she was still focused primarily on California, I went with her to a meeting of the Los Angeles City Council, where she would discuss the necessary but rather tedious subject of building codes and still be greeted like a rock star, with one council member proposing an “I Love Lucy Jones” night at a local restaurant. While sitting on a hard bench awaiting her turn to speak, she took out her iPhone and clicked on an e-mailed video of a landslide. Trees, rocks and dirt all hurtled down a slope and over a roadway, suddenly more fluid than solid. As she watched it, Jones—whose brown bangs and spectacles make her look far younger than her age—radiated delight, as if the earth had a secret that she was being let in on.

“Some people don’t like my style,” she told me later, referring to how excited she gets about the earth moving. “They think I’m, like, a little too enthusiastic. I shouldn’t be enjoying myself that much in a disaster.”

But enthusiasm—for knowledge, for inquiry and for putting both to work—has driven not just her mastery of geophysics but her ability to communicate that know-how with others, and probably save lives in the bargain.

“We have an irrational fear of earthquakes, partly because they create a feeling of being out of control,” she says. “We’re afraid of dying in them, even though the risk is extremely small. You’re almost undoubtedly going to live through it. And probably your house is going to be OK. It’s the aftermath that we need to prepare for.”

Amy Wallace, a journalist in Los Angeles, has both experienced and written about earthquakes.