Meet the Mighty Spinosaurus, the First Dinosaur Adapted for Swimming

A mysterious mustachioed man helped paleontologists piece together the life story of the long-lost, semi-aquatic “Egyptian spine lizard”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/b7/ccb75f5d-da77-4484-abe7-d4e69077b292/spinosaurus_mm8284_ngm_102014_001edit.jpg)

In 1915, German paleontologist Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach described one of the weirdest dinosaurs known to science: the “Egyptian spine lizard” or Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Unearthed at a dig in Egypt three years earlier, a few things set Spinosaurus apart right off the bat. Its lower jaw had a squared off-end and its mouth was filled with unusual teeth that might have been used to catch fish. The fossil also sported long back spines, prompting Stromer to make a comparison to a crested chameleon.

The Egyptian fossils—vertebrae and a skull piece—eventually went on display at a paleontology museum in Munich, but the rise of the Nazi regime brought only loss for Stromer, a staunch critic of the Third Reich. He lost two sons to the war, and an Allied air strike on Munich destroyed the remains of S. aegyptiacus. Since then, only a few isolated Spinosaurus bones and teeth have shown up in fossil beds around the world. Without a more complete skeleton, the true nature and appearance of the mysterious dino was left up to speculation (and the imagination of Jurassic Park III animators).

Now research funded by the National Geographic Society and published today in the journal Science re-introduces the world to this bizarre ancient predator—and reveals that the animal probably spent its life both on land and in water.

“Dinosaurs were far more diverse and adaptable than we give them credit for,” says Nizar Ibrahim, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago and a National Geographic Emerging Explorer.

Stromer’s work in Egypt is in part what inspired Ibrahim to travel to the Sahara in search of African dinosaur fossils. While working on his doctorate degree in April 2008, Ibrahim stopped in a town called Erfoud, and a man with a mustache approached him with a cardboard box full of dinosaur fossils. The man, a local fossil hunter, wanted Ibrahim’s expertise in identifying the bones. Most were encased in sediment, but one struck Ibrahim’s eye: a long, blade-shaped bone with a reddish cross-section. “I had never seen anything like it before. I thought maybe this is a rib or maybe, just maybe, it could be the spine of a Spinosaurus,” recalls Ibrahim.

He brought the fossils back to the Université Hassan II in Casablanca, thinking he might one day pin down their identity. In 2013, he heard from his Italian colleague Cristiano dal Sasso, also a co-author, that the Natural History Museum of Milan had acquired a possible Spinosaurus specimen. On a visit, Ibrahim found himself facing a partial skeleton of what appeared to be Spinosaurus laid out in the museum’s basement.

The museum staff suspected the bones came from Morocco, but a private collector had donated the fossils, making it harder to interpret the find. “In this case, it was difficult to tell whether all of these bones came from the same place without the actual context,” says Ibrahim.

The bones had the same cross-section coloration as those in the cardboard box, so Ibrahim and his colleagues resolved to track down the source: the man with the mustache. After weeks trying to find him, the team was having tea at a café in Erfoud when a tall figure dressed in white walked by. “I just got a glimpse of his face,” says Ibrahim. “But I knew it was him.” They ran after the man, and with a bit of convincing, he took them to the place where he’d found the bones: an almost cave-like hole in a cliffside in the Sahara’s Kem Kem fossil beds.

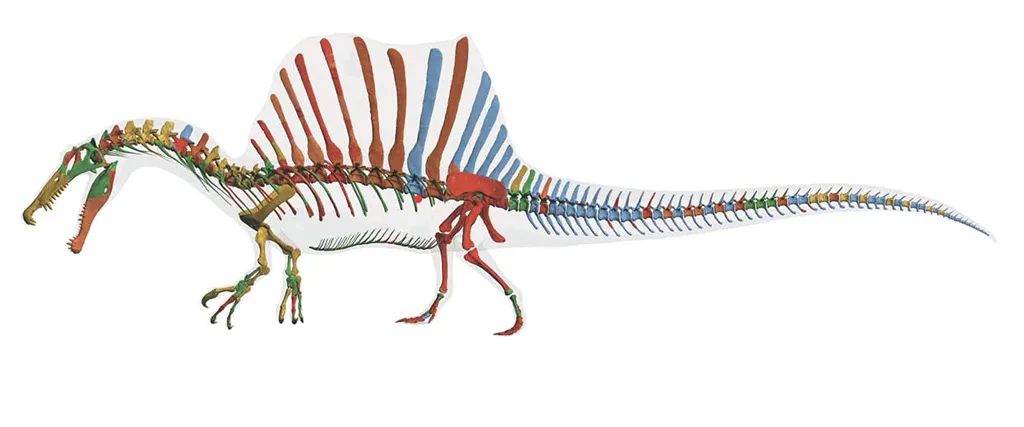

Further excavations revealed more spines and other Spinosaurus bones, all likely belonging to one individual that lived in the area around 97 million years ago. The team sifted through photographs, drawings and field books belonging to Stromer and confirmed that this new specimen was the same species. To reconstruct the skeleton, they took computerized tomography (CT) scans of the newly discovered fossils as well as some from museums around the world. From Stromer’s archives, they created digital models of the jaw and vertebrae he first described, then they 3D printed a composite skeleton and created a flesh rendering.

At 50 feet long, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus exceeded the size of Tyrannosaurus rex by 9 feet. Its spines were at most 6.5 feet tall—around the average height of a professional basketball player. “It was an incredibly large dinosaur, especially as far as predatory dinosaurs go,” says Matt Lamanna, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh who was not affiliated with the study.

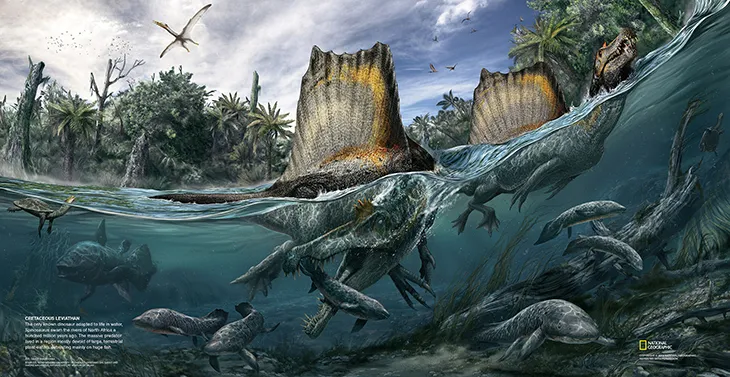

The Kem Kem beds mark what was once a tropical river system, a predator’s paradise. Other inhabitants included car-sized coelacanths, sharks, crocodiles, flying reptiles and close relatives of T. rex. “I call this place the most dangerous place in the history of our planet. It’s full of predatory dinosaurs. That’s really unusual,” says Ibrahim.

What really makes Spinosaurus special are its unique adaptations that may have allowed the dinosaur to hunt underwater. Like crocodiles, Spinosaurus had a long narrow snout with nostrils mid-skull, perfect for submerging. It also had a second pair of openings, likely neurovascular slits that are also found in crocodiles. Spinosaurus had a long neck, like a heron or a stork. Large, cone-shaped teeth and powerful, clawed arms might have been used to catch and eat fish, a behavior supported by previous oxygen isotope analysis that pointed to Spinosaurus being a pescatarian.

Spinosaurus’s pelvis was small but attached to powerful, short legs, similar to the ancient ancestors of whales. Its big feet had flat claws, a structure that may have been useful for paddling. Loosely connected tail bones could have allowed the animal to propel itself forward in water just like a fish, and its densely packed bones resemble those of a penguin.

“It was a chimera: half duck, half crocodile. We don’t have anything alive that looks like this today,” says study co-author Paul Sereno, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Chicago.

“The great remaining mystery is the function of those long spines on the back vertebrae,” says Hans-Dieter Sues, a vertebrate paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History who was not affiliated with the work. Previously, researchers suggested that the spines might be embedded in a hump, similar to the ones on buffalo used for fat storage and display.

Instead, Ibrahim and his team detected potential evidence of skin attachments along the spine that could have created a sail-like structure. “If you’re mostly swimming around and spend a lot of time submerged in the water, the sail is the one part of your body that’s going to stick out and be visible from far away,” explains Ibrahim. “The size of your sail could tell [other animals] something about your age, your size, to ensure that they don’t come and enter your fishing grounds.”

While aquatic reptiles did exist in the ancient past, the idea of an aquatic dinosaur has put paleontologists at odds for decades. “Without a time machine, it’s impossible to know what any extinct animal did,” says Lamanna. And while a semi-aquatic lifestyle is just one possible explanation for Spinosaurus’ adaptations, multiple lines of evidence back up the theory that this dinosaur might have been aquatic, he says.

Sues agrees: “It seemed that dinosaurs were mostly land-dwelling animals. Spinosaurus has now changed that picture again.”

An exhibition entitled “Spinosaurus: Lost Giant of the Cretaceous” will feature the find at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C., from September 12, 2014 to April 12, 2015. It includes the digital model, 3D printed skeleton, and fleshed out rendering of what Spinosaurus aegyptiacus might have looked like. The swimming dinosaur will also be the topic of a National Geographic/NOVA special airing on PBS Nov. 5 at 9 pm, and a feature story in the October issue of National Geographic magazine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)