Modern Humans Have Become Superpredators

Most other predators target juveniles, but our species tends to kill more full-grown adults

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/84/7384d6b5-c25b-40c9-99e2-9d1e6957d2be/istock_000013862148_large.jpg)

The human species really is unlike any other predator on the planet, especially when it comes to our choice of prey. Across the animal world, predators focus their efforts on juveniles. Humans, by contrast, are far more likely to be killing big strapping adults, particularly among carnivores on land and fish in the ocean.

“Adult individuals provide the ‘reproductive capital’ of a population, akin to the financial capital in a bank account or retirement fund,” Dalhousie University biologist Boris Worm notes in a commentary that accompanies the study, published today in Science. “Depleting the capital is risky, particularly in long-lived, late-maturing organisms.”

The new study got its start back in the 1970s, when Thomas Reimchen of the University of Victoria was studying predator-prey interactions in a remote Canadian lake. There, 22 species of trout, loons and other predators fed on stickleback fish. Despite the number of predators, the stickleback population remained steady. This was because the predators overwhelming consumed fry, juveniles and sub-adults, eating only 5 percent of the reproductively valuable adults each year.

“This situation contrasted dramatically with the commercial fishing I observed in adjacent marine waters, which were taking from 40 to 80 percent of the biomass of salmon and herring, and then predominantly the reproductive-age classes,” Reimchen recalled at a telephone press conference held on Wednesday.

Inspired by this ecological disconnect, Reimchen began collecting data from other studies that had looked at predators, including humans, and the characteristics of the prey they were consuming. Eventually, he and his colleagues gathered more than 2,200 data points on 399 prey species from every ocean and all the continents except Antarctica.

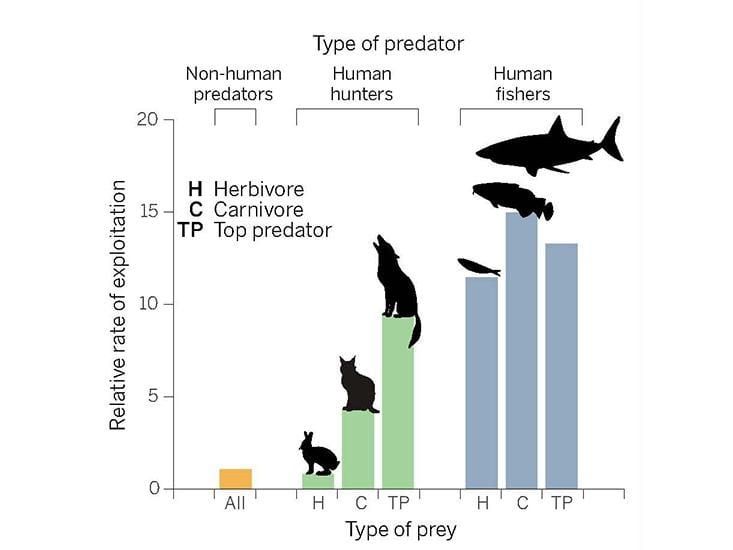

In some cases, such as with herbivores on land, they found that humans kill adult prey at about the same rate as non-human predators do. But the harvest of adult carnivores by humans was nine times that of other large carnivores, which were mostly killing each other through competition. In the oceans, the situation is even more dramatic. Marine predators harvest about 1 percent of adult biomass each year. Humans take a median of 14 percent—and as much as 80 percent or more in extreme cases.

Humans target adult animals for many reasons. When processed, older animals provide more meat for the effort. Also, most fisheries and wildlife management schemes specifically call for adults to be harvested, because in theory it frees food and other resources for juveniles, lead author Chris Darimont of the University of Victoria noted at the teleconference.

“Those juveniles then grow to become adults available for harvests in the future,” he said.

But this practice can have ramifications for a population, Darimont said, especially among fish. Old, large fish tend to produce the most offspring, sometimes hundreds of thousands of eggs in a single year. Removing those fish dials back the reproductive capabilities of the population, and it can also affect the evolution of a species. Cod, for instance, can live for more than two decades and usually start breeding around six years old. But due to fishing pressures, they currently begin breeding at four-and-a-half years old and produce fewer offspring.

The human species was able to become a superpredator through technology, which has allowed us to escape the limits usually found in predator-prey relationships. Better weapons mean that hunting and fishing are relatively safe activities, at least compared with animal hunts. Use of powerful boats and better nets means people can access deep oceans where our bodies would not survive. People can purse prey at high speed with cars and airplanes. Industrial-scale processing and refrigeration and freezing allow a human to take far more individual prey than they alone could eat. And consumers don’t have to live or work anywhere near the site where the prey lives.

Also, in natural systems, predators tend to dwindle when prey does, Darimont noted. Humans, though, not only subsidize their survival with agriculture, but they also often value certain species more highly for reasons that have nothing to do with food. “The recent spike in poaching of rare animals in Africa provides a striking example,” he said.

Transforming humans from superpredators into something more sustainable will require imposing many limitations, the researchers say. But there are some models for how it might be done. Darimont pointed to the traditional herring fishery in the Pacific Northwest, in which fish eggs (highly prized in Asia) are harvested from the kelp where they are laid rather than from the dead bodies of adult herring. And the lobster fishery in Maine has long had size limits that ensure the largest lobsters are left in the water.

Darimont adds that we'll also have to overcome some deeply held societal beliefs: “If future generations of people are to see large carnivores, then this requires cultivating new tolerance for living with them. This might include increasing revenues to local communities derived from nonconsumptive ‘uses,’ such as eco-tourism [and] shooting carnivores with cameras, not guns.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)